Last week, I wrote that I was wincing at the valuation for the US stock market (click here for the article) and said that I thought that returns in the coming years would be lower than the historic averages.

Importantly, I said that returns could be low without a crash in the form of lower average returns. I wish I had also said that even though the average return might be lower, the volatility would probably be average, so the road to low returns won’t be easy.

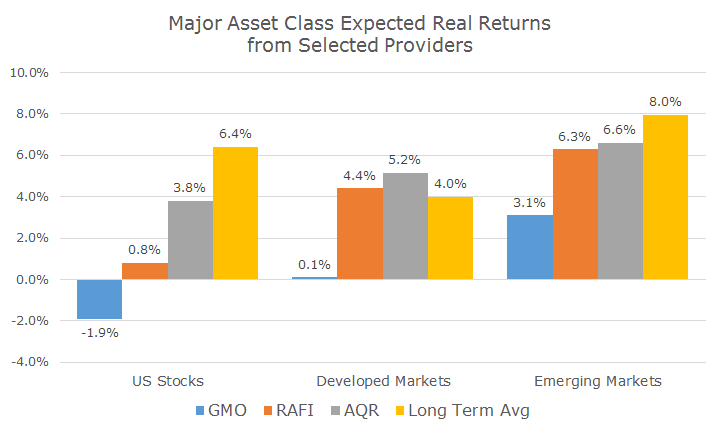

Today I thought I would share some estimates from large, well-known and well-respected asset management firms that offer expected returns for major asset classes. I am going to show the chart first, but keep reading because there are many devils in the details.

This chart shows the real (net of inflation) expected returns for three major asset classes from three large (all have more than $100 billion in assets under management), well respected money management firms. To put these in perspective, I’ve also included the long-term realized return for each asset class net of inflation.

The first set of forecasts (in blue) from GMO (Grantham Mayo van Otterloo) are the most bearish. Their outspoken leader, Jeremy Grantham, correctly said that US stocks were in a bubble in 1999 and then said they were a great buy at the near the bottom of the 2008 financial crisis.

The GMO forecasts, highlighted in blue, are actually seven-year forecasts (as opposed to 10-years). They believe that after inflation, the returns for US stocks will be negative, flat for developed markets and moderate for emerging markets.

Although GMO isn’t as transparent as the others about how they create their forecasts, they do say that they are based on mean reversion – profit margins, earnings growth and valuations will fall to their long-term averages in seven years.

The second set of forecasts, in orange, are courtesy of RAFI, or Research Affiliates. To calculate their 10-year forecasts, RAFI adds current dividend yields to growth estimates and then lowers valuations back down to their long-term averages (their full methodology for stocks can be found here).

The third manager, AQR (an acronym for Applied Quantitative Research) uses a method that is akin to RAFI’s (although they wouldn’t like it if they heard me say that) in that it looks at the current yield, estimates growth and assumes that valuations will get back to average on a Shiller PE basis.

All of these forecasts share some common themes. First, they all see stocks as overvalued and assume that valuations will be closer to the long run average in the coming years.

A note about the long-term averages in my chart: they all have different time horizons. The US data goes back to 1926, the developed international to 1970 and the emerging markets data to 1982. That inconsistency, in my opinion, probably overstates the long-term numbers for US stocks while understating them for the other two asset classes.

The second common theme from these three managers is that they all think that US stocks are the least attractive and emerging market are the most attractive of the bunch. (It’s useful to remember, however, that there are far more than three large, respected firms out there – these are three that I either happen to like for one reason or another).

Returns in the US have been hot over the last five years while emerging markets have suffered: 16.4 vs -1.2 percent using the S&P 500 and MSCI EAFE EM. As a result, most investors prefer to hold US stocks even though sensible analysis would suggest otherwise. As a contrarian that makes sense because for an investment to be cheap, it has to be out of favor.

Of course, there’s more to market movements than valuations – as I’ve said since early 2014 (when I first noted that US stocks were overvalued), the market’s momentum can move prices for a long way and a long time.

While I think all of these forecasts are reasonable and draw some useful conclusions, you can be sure that I’m not going to make any ‘bet the ranch’ bets based on them. In fact, I don’t take much from the actual numbers, but I do think the exercise is useful for thinking about the big picture.

I am definitely bullish about the future, but even a congenital optimist like me knows that some times are better than others and any reasonable person would say that the next five years won’t be like the last five.