So far, 2016 has been full of surprises, but most of the attention has gone to wildly volatile oil and stock prices. Less noticed, but equally important, has been the boost on bond prices, as seen by the dramatic fall in bond yields.

The 10-year US Treasury note, the bellwether benchmark, started out the year yielding 2.27 percent, 10 basis points (a basis point is one hundredth of one percent) higher than the 2.17 percent yield at the close of 2014. In just over a month, the yield has fallen to 1.86 percent, levels that we haven’t seen since last April.

The drop in yields are even more dramatic at the short end of the yield curve. The yield on the two-year US Treasury note started the year at 1.05 percent and is now 0.71 percent, a difference of 34 basis points.

If you don’t think in yield terms, try this on for size: the Barclays US Aggregate bond index, which includes all taxable, investment grade bonds in the US (other than TIPs) is up 1.59 percent this year, which is an annualized gain of 16.86 percent.

Obviously the index won’t achieve that return (how far would rates have to fall for that to happen?), but it’s useful to understand just how dramatic the move in bonds has been over such a short time. The Agg isn’t as sensitive to interest rate shifts as the 10-year, but you get the idea.

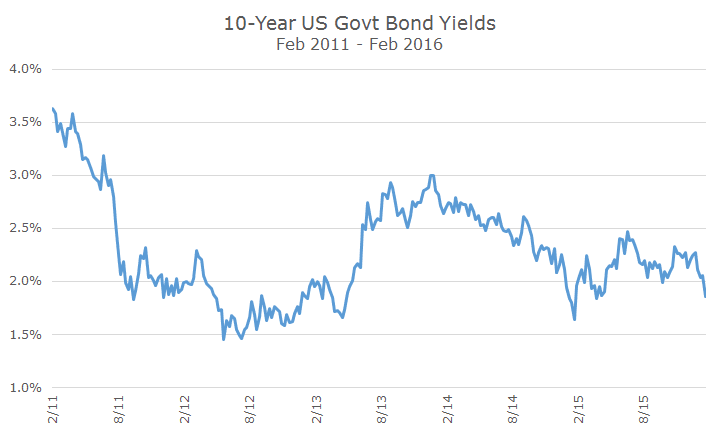

The chart below shows the weekly closing yield for the 10-year US Treasury for the last five years and you can see the range is between 3.63 in February 2011 and 1.45 in June 2012. It actually closed as low as 1.39 percent when you look at the daily data, but I wanted to show five years’ worth of history and you can only do three years with daily data.

The 10-year yield was the highest at the beginning of this period and you can see a sharp decline in mid-to-late 2011 when the Fed was preparing Operation Twist in between the second and third round of quantitative easing.

Yields stayed on the floor for about two years and then shot up in mid-2013 when Bernanke hinted that the Fed may ‘taper’ off their bond buying program, a period known as the taper tantrum. After that, the yield mostly drifted lower and then shot down sharply last January when stocks were off sharply (sound familiar?). That dip left as quickly as it came and yields were fairly stable until last month.

The question now is whether the current drop in yields will reverse itself quickly like it did last year or whether it’s a new period of low rates like 2011-2013. Sadly, I don’t have the answer to that question, but I do have a few observations that you might find useful.

First, just when you think that interest rates can’t go any lower, they totally can! I learned that lesson a few years ago and cited the long-running low rates there as the perfect example of how rates can go lower. At that point, I couldn’t conceive of actual negative rates, but Japan is negative all the way out to nine years – the 10-year currently yields 0.06 percent, making our levels look downright juicy.

Second, the rally in bond prices this year is a good reminder of why we own them: they are a ballast to the portfolio, are lowly correlated to stocks and serve as a haven during ‘risk-on’ times. Sectors without credit risk fared even better than the Agg while stock sensitive to bonds like high yield suffered, just as you would expect. You may not feel like your portfolio is ‘working,’ but it is.

Third, the Federal Reserve controls the short-end of the curve, but longer-term bonds are affected by a whole host of factors in addition to what the Fed does or doesn’t do. Over the past few years, I’ve been asked about what will happen to bond prices when the Fed raises rates.

Well, now the Fed has hiked rates and bond prices have risen – the Agg is up 1.50 percent since the December meeting. Obviously, this time period is too short to draw a meaningful conclusion, but the Fed and long rates aren’t as connected as a lot of people think (remember Greenspan’s conundrum?).

As I’ve said many times before, I am looking forward to when rates increase. It won’t be fun getting there, but as investors, earning 1.86 percent on a 10-year bond is for the birds!