One of my most vivid memories from the 2008 financial crisis was when the yield on the US three-month Treasury bill turned negative. Investors were so scared about what might happen that they were willing to pay so much for short-term bills that they would accept negative yields. Investors knew with certainty that they would get back less than their investment.

I printed the screen because I thought it was sort of a once-in-a-lifetime type moment, but now it doesn’t matter that I lost it because six years later, negative yields are popping up all over.

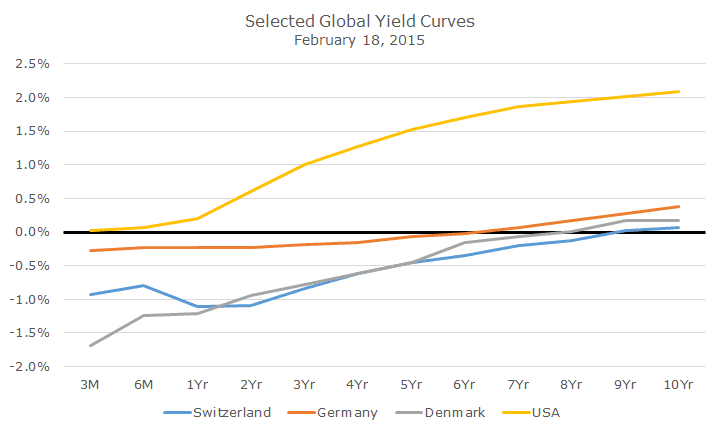

The chart below shows the yield curve out to ten years for three countries: Denmark, Switzerland, Germany and the good ol’ United States of America.

To the left, you can see that with the exception of the US, interest rates in these three countries are negative: wildly negative if you ask me. I’ve indicated the zero line in dark black to show that investors won’t receive positive yields on their bonds unless they buy six to eight year matures – and even then, it’s next to nothing!

It makes the low rates in the US look positively smashing. Of course, I have cherry picked the rates that I put on the chart. You could see some big numbers if I had put up the curves for Greece or Russia, but I’ll bet those don’t sound very appealing to you either.

Even still, there are other countries that have negative yields out to four years including the Netherlands, Sweden, Austria, Belgium, France and Finland.

What does it mean that investors are willing to buy bonds with negative yields – and not just for the next three months like US bills in the 2008 crisis – we’re talking about five year bonds with negative yields.

First and foremost, it means that investors are not worried about inflation, which is normally the biggest risk for bond investors. Over time, inflation erodes purchasing power, so you want an interest rate that will compensate you for your estimate of inflation plus a little something in case your estimate is too low.

An investor willing to sock away money for five years knowing that they will get back 2.5 percent less than what they started with (0.50 percent for five years, roughly), thinks that inflation could possibly be negative – or what they call deflation.

If deflation comes in at 2.5 percent, then losing money on your bond is no big deal because your purchasing power is unchanged from today. Well, maybe no big deal isn’t right, because everyone wants to earn something above and beyond inflation, but you get the idea.

Also, like the 2008 financial crisis, there is some fear built into these yields. Take notice that the yields are lowest in countries right next door too, but not actually in the eurozone. European investors in the eurozone can keep their money close to home in Switzerland, Denmark or Sweden while still keeping it outside of the euro.

If you live in Germany, and the euro continues to get weaker or even breaks up (unlikely, but possible), having some money in Danish or Swiss bonds may be a great deal based on the currency movements even if the yields are negative.

For me, one of the most interesting implications is the idea that yields can fall meaningfully below zero and stay there.

When rates were falling through 2012, people would say, ‘Dave, rates are at historic lows and they can’t go much lower!’ I would reply, ‘until they get to zero, they can always go lower.’

It turns out that I was wrong, the yield environment today proves that yields can go lower still, which, believe it or not, makes it rational to buy bonds at a negative yield because as long as the yield goes even lower, you can still earn a positive return.

I know that’s nuts, but, honestly, we’re in a crazy mixed up world at the moment.