In recent months, I’ve been working to create a set of ‘primers’ that describe certain market factors that we pursue in our strategy in hopes of increasing returns, lower risk, or, in a perfect world, doing both.

So far, we’ve looked at three equity factors: size (small companies tend to outperform large companies), value (cheap companies tend to outperform expensive companies) and momentum (stocks that have recently outperformed/underperformed are likely to continue that trend in the short run).

Today’s primer is focused on quality, the tendency for high quality companies to outperform low quality companies. It’s an intuitive, long-standing idea, but it’s still a little controversial because it contradicts one of the basic ideas in finance: to earn higher returns, you have to take more risk.

Warren Buffett may be the most famous advocate of quality investments and is famously quoted as saying that ‘it’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.’ Buffett is most famous as a value investor, but obviously insists on quality as well.

His mentor, Benjamin Graham, published a list of seven criteria for stock selection in the 1973 publication of the Intelligent Investor that include:

- Adequate Size.

- A sufficiently strong financial condition.

- Continued dividends for at least the past 20 years.

- No earnings deficit in the past ten years.

- Ten-year growth of at least one-third in per-share earnings.

- Price of stock more than 1.5 times [book] value.

- Price no more than 15 times average earnings of the past three years.

Value investing focuses on the market value of a company (price) versus some fundamental accounting metric (book price, earnings per share, sales, etc.). Notice that in Graham’s list of seven criteria, only the last two are value oriented – the rest are geared toward company value!

Academia largely ignored the concept of quality for decades, probably because under the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), measures of quality should already be reflected in the price.

Furthermore, the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and its subsequent anomalies generally suggest that in order to earn higher returns than the market, investors need to take additional risk – that’s true for size and value, but as we noted with momentum, that concept doesn’t hold.

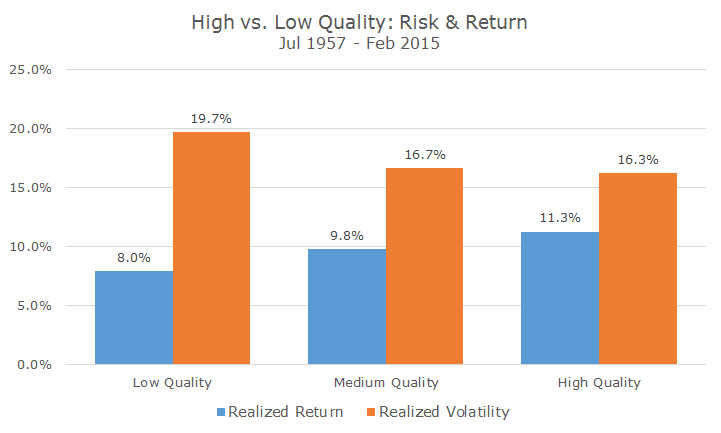

The relationship between high and low quality is like momentum in that the lower quality firms are riskier in the business sense and have experienced more price volatility. On the chart below, you can see returns are higher (in blue) as firm quality increases, but volatility (in orange) drops.

The data for the chart above comes from a paper by Cliff Asness, Andrea Frazzini and Lasse Pedersen, all of whom are affiliated with the investment management company AQR. Click here to read the paper and see the data.

The AQR gang aren’t the only ones that have worked on this issue in recent years. Another well-known academic, Robert Novy-Marx found that gross profits over assets is a terrific proxy for highly profitable companies that tend to outperform less profitable firms. His measure differs somewhat from the AQR folks, but the basic argument is the same.

The big question remains: why should higher quality (or more profitable) firms outperform other firms – why don’t prices already reflect their quality? It’s not as if these attributes aren’t fully known to the market.

The answer, unfortunately, is that no one really knows. The most plausible answer is that investors are willing to pay more for higher quality firms, as you would expect, but not as much as the additional quality may be worth. Higher quality firms do have higher prices, on average, but investors should be willing to pay even more for them, leaving room for higher returns until that time comes.

We can see in the data that quality has been a great investment in the US since 1957 and in 24 developed markets dating back to 1986. And, unlike some of the other strategies, investing is comforting.

Buying micro-cap and value stocks can invoke anxiety and with momentum, you worry about trading costs and taxes. Quality, on the other hand, makes you feel nice and cozy, which is nice, but feels odd since good investments usually require a strong stomach.