When the Swiss National Bank (SNB) broke their peg to the euro, the Swiss franc shot up 17 percent overnight. Investors that owned Swiss francs had a fantastic return and those that had bet against the franc, or gone short francs, lost an equivalent amount (more details here).

That shock caused several currency brokers around the world to fold, although the biggest firm, FXCM managed to stay afloat thanks to an emergency capital injection from a U.S. investment firm (the capital injection came with some onerous terms, as you might expect).

These currency brokers generally allowed their customers to use leverage to trade currencies, sometimes as high as 100:1. That means that for every $1 invested, you could go long or short $100 worth of Swiss francs, euros or whatever your heart desired. Other firms were only allowed leverage of 50:1.

When the SNB dropped their bombshell, those investors that were short Swiss francs were wiped out. If a customer goes under, the firm is on the hook and if too many clients fail, then the firm can go under, which is what happened a few weeks ago.

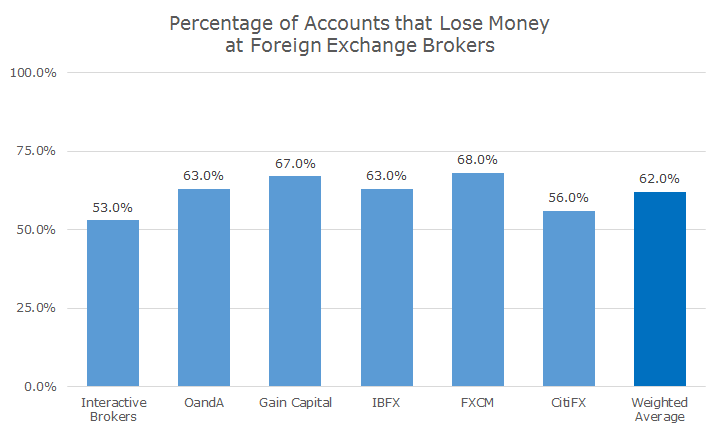

In their reporting on the currency brokerage failures, the Wall Street Journal had an interesting article with the title: Six in Ten Mom-and-Pop Currency Traders Lose Money Each Quarter. Apparently, FXCM, and other brokers have to report how many of their clients are profitable each month and the numbers are astounding, as outlined in the table below.

To be fair, I don’t know what those percentages are for stock and bond traders, and at trading houses where people buy with a lot of leverage, I assume that they are equally high. I don’t think foreign exchange is inherently bad – I think trading, especially with leverage, is the real culprit here.

That said, I decided to do a little digging on currency trading just to see what I could find.

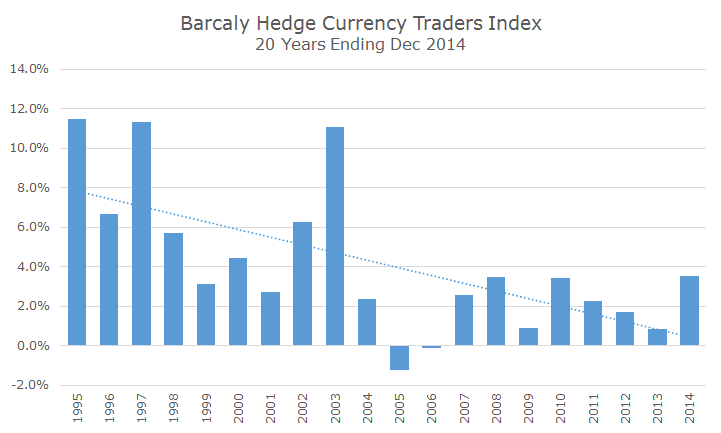

First, I looked at what professional currency traders have earned according to data aggregator, Barclay Hedge (which is unaffiliated with the British Bank). Barclay Hedge keeps track of the performance results for Commodity Trading Advisors (CTAs), which are firms that trade futures contracts.

It would appear that the professional traders are in fact better than the Mom-and-Pop investors that the Wall Street Journal describes.

Over the last 20 years, the Barclays Currency Traders index has gained 4.14 percent per year, which is better than cash at 2.67 percent, but not quite as good as the Barclays Aggregate Bond index (which is affiliated with the bank), which earned 6.23 percent.

A casual glance at the chart suggests that returns are harder to come by today than they were in the past. I don’t know this, but it would seem to me that lower interest rates explain lower currency returns.

My view is that the long-term expected return for currencies is basically zero. That’s pretty much what the data shows as well. Investors who take their foreign currency and buy stocks or bonds may fare better, but that’s mostly because of the stocks and the bonds, not because of the currency.

We have foreign currency exposure in both our stock and bond portfolio. The entire non-US stock portfolio is unhedged, so we get foreign currency exposure there. While we do have non-US bonds in our portfolio, only a very small portion of them are left unhedged with currency exposure.

Stocks are volatile enough on their own that you don’t really notice the additional volatility that currency exposure brings. That same currency volatility swamps bond volatility, so we hedge that out for the most part.

Leaving some non-US currency exposure provides some diversification benefits that are worthwhile in the long run, despite the recent short-term strength of the dollar.