Just as I enjoy and learn from Warren Buffets annual letter to Berkshire stockholders, I also read and get a lot of value from the annual report from Yale’s endowment. Here’s a link to the current report.

Yale’s endowment is the largest in the world and has enjoyed spectacular investment performance, particularly under the stewardship of David Swensen, who wrote one of my favorite investing books of all time, Pioneering Portfolio Management.

When I first looked at this year’s report, I was struck that their oft-copied strategy, hasn’t performed as well in the last five years as a conventional strategy like ours. Let me quickly say, however, that their long-term performance since Swenson took over is still phenomenally good by any standard.

Still, over the last five years, their portfolio has earned 3.3 percent, had volatility of 17.6 percent for a Sharpe ratio of 0.19 percent. Our model portfolio for a 60/40 stock/bond mix, earned 5.0 percent with volatility of 13.8 percent, for a Sharpe ratio of 0.36 over the same period. For our numbers, I used index returns, so there is no manager over or under performance, and applied a one percent to show results net of fees.

These results are partly a function of the measurement period, Yale reports based on their fiscal year that ends in June and so I copied that for comparison purposes. Looking at these non-calendar returns, though meant that these numbers caught the second half of the 2008 Financial Crisis and our strategy fared much better during the crisis.

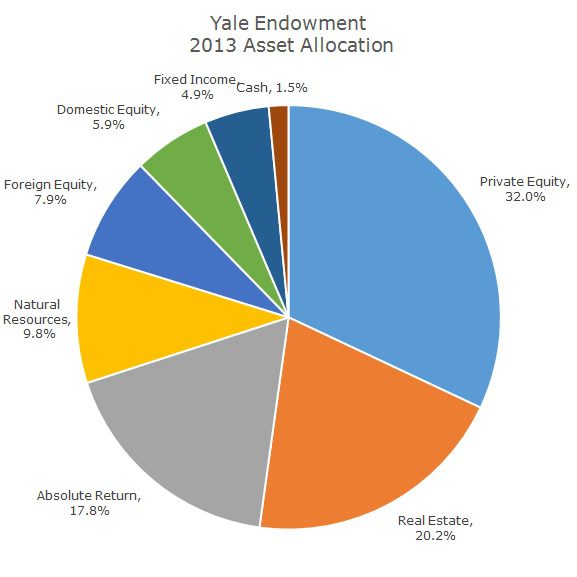

Here’s a look at their 2013 asset allocation:

Their four largest asset classes, which make up nearly 80 percent of their portfolio are not investments that we can replicate. In fact, most investors can’t and when Swensens book was first published in 2000, the ‘Yale Endowment Model’ of investing became very, very popular. Unfortunately, the vast majority of those follow-on investors failed to get adequate returns and many were just in time for the 2008 crisis, when the strategy really suffered.

A great deal of their excess returns come rely on strategies with built in illiquidity, which means that you can’t get your money out quickly. In the report, Yale offers as special call out box to explain their strategy of illiquid investments saying, ‘Invest willing to accept less liquid investments enhance the opportunity to outperform the market. Intelligent pursuit of illiquidity is well suited to endowments, which operate with extremely long time horizons.’

Our clients, who might have a few decades, but whose time horizon isn’t infinite like it is for an endowment, can’t afford to tie up their money for five, ten or more years in order to earn additional return. It might make sense for a small part of the portfolio, but certainly not 80 percent of the portfolio.

Almost all of the investments that we own (95+ percent) are highly liquid and can be sold immediately without impacting the market price. Even that small five percent remainder can be sold, it just might take a few days. Compared to Yale’s portfolio, that few day delay is nothing – how long do you think it would take to sell thousands of acres of timber? A long time is my bet.

In addition to the extremely long-time horizon that an endowment enjoys, they also have the benefit of not worrying about taxes.

Our clients definitely have money in IRA and other tax-deferred accounts, but most of the money that we manage is in taxable accounts and we have to factor in the tax consequences of our investments. Even if we could, it probably wouldn’t make sense to allocate 17 percent of a taxable portfolio to absolute return strategies that aren’t very tax-efficient.

Lastly, I wonder if some of these strategies will fare as well in the future as they have in the past. About two years ago, I went to a conference dedicated to private equity investing. I wanted to see if there was a way that we could participate and there really isn’t.

One of the sessions was a roundtable of the attendees talking about the expected returns from private equity. One old timer in the room asked all of the young bucks what they had modeled for the expected returns. Most of the answers were around 12 percent, just three of four percent more than the groups expected return for public stocks.

The old timer leaned back and said, ‘Man-o-man, back in the day, 20 years ago, we didn’t even think about touching a private equity deal that didn’t have a 30 percent expected return.’ The group wistfully talked about the old days and wondered aloud whether it really made sense to give up liquidity for an extra three or four percent a year in return.

I don’t think that the ‘Yale Model’ is broken, but I am certain that it’s not for all investors and as we can see from the past five years, it doesn’t always offer the most competitive returns.