Last week, I had a very enjoyable meeting with a valued client and long-time reader. In the meeting, he said that I should publish some of my old Daily Insights now and again, something I plan to do from time to time when I don’t have an idea (like now) on periodic Throwback Thursdays.

The commentary below dates back to August, 2011, when stocks lost more than 15 percent in the course of two weeks. It was meant as a bit of a reminder and a pick-me-up and I think it looks pretty good six years later (I did update the data tables). Let me know if you like it by clicking either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ at the bottom.

**

My goal is to provide investment commentary that is interesting and informative, but also, hopefully, a bit of cheeky fun.

The recent market decline and spike in volatility, though, is no joke. With investor anxiety rising, now is a good time to step back from the day-to-day news and events and remind ourselves of why we invest in stocks in the first place.

Evidence

First, let’s start with the facts.

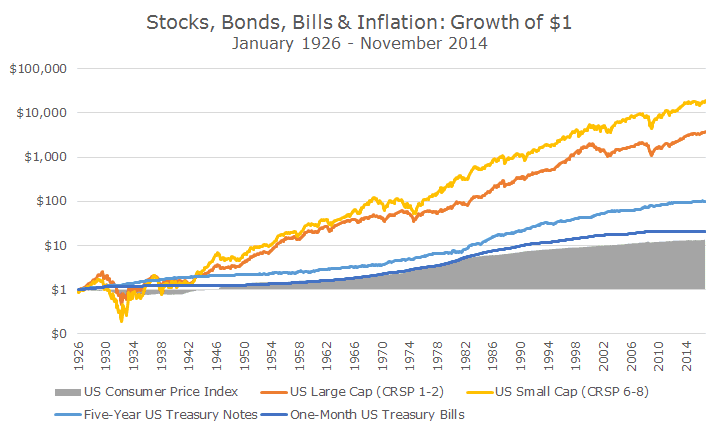

Over the past 100 years, regardless of what country you look at, stocks have outperformed other investment assets like cash and bonds. In the U.S, where we have the longest and most complete data, the results are compelling:

Notice that the scale is logarithmic, which helps put things in percentage terms – after all, a 1,000 point drop in the Dow Jones today is a big deal, but not nearly as big as it would have been in 1982, when the Dow Jones was 1,084.

As you can see from the chart, inflation over this period grew by ten-fold. Money kept in cash (defined as one-month Treasury bills) outpaced inflation, gaining 20-fold. Bonds did better yet, growing by 90-fold. These investments had good results, but stocks won by a mile, gaining almost 3,000-fold.

Over lunch this past weekend, I started to bring up results over the last century, and was politely interrupted by a former economics professor, who said, “David, that 100 years argument is baloney.” (OK, he didn’t use the word baloney, but this is a family newsletter.)

He had an excellent point, which was that although the historical evidence is largely indisputable, it doesn’t tell us what will happen in the future. He joked that “past performance isn’t necessarily indicative of future performance,” and he’s right – up to a point. The fact that stocks outperform bonds and cash is not based on random coincidence.

Theory

The predominant theory is that stocks are riskier than bonds and, therefore, stocks require a higher return to make them palatable to investors. Said another way, if stocks are inherently risky and bonds are relatively safe, why would anyone invest in stocks unless they had reason to expect compensation above and beyond the return on bonds?

When we talk about the levels of risk associated with stocks and bonds, we are often referring to volatility, but there is an even more fundamental kind of risk.

Remember that at the most basic level a bond is nothing more than a contract between a borrower and a lender.

Stocks represent ownership in a company. As an owner, investors receive all of the benefits of increasing profitability and value, but risk the loss of the entire investment. In the case of bankruptcy, bond investors are paid off in full with interest before stockholders receive anything, so stocks represent a ‘residual claim’ on any remaining value.

In technical terms, the value of any investment is the present value of its future cash flows. The present value of the future cash flows is determined with a ‘discount rate.’ For example, if an investment has an expected payoff of $100 in one year’s time, investors will discount the investment based on how risky they think it is.

If it is a low risk investment, investors might only apply a three percent discount rate and pay $97. If it’s a high risk investment where they are not sure about the $100, investors might use a discount rate of 50 percent and pay $50. The discount rate reflects the investor’s perceived risk of the investment.

With a standard issue bond, all of the cash flows are known in advance and there is a defined beginning, middle and end. Those cash flows are generally discounted by the expected inflation rate plus some additional compensation for the term of the loan and the creditworthiness of the borrower.

Stocks, on the other hand, have very uncertain future cash flows (if any) and investors must discount their estimates of those cash flows to a much greater extent to compensate for the higher degree of uncertainty. That discount rate is often thought of as the ‘cost of equity’ and should ultimately be equal to the expected rate of return, which is higher than the expected return for bonds.

Risk and Return are Related

Even if the theoretical description is a little too technical to understand at first blush, the basic idea remains that stocks are inherently riskier than bonds, but the reward potential is also greater. Most people understand this at least in part by looking at the results of their own investments.

If we measure the standard deviation of returns from 1926 through 2010 (this represents the most complete data set), we can see that stocks are about four times more volatile than bonds.

Conclusion

In short, it should be no surprise that risk and return are related.

Looking at the evidence and the theory, it becomes apparent that stocks are riskier, but the opportunity for return is much greater. If you can get through the volatility and inevitable downturns (financially and emotionally), then over a long time horizon, stocks should provide an ample reward as compensation for the risk.

Today, with cash earning effectively zero and 10 year bonds yielding approximately two percent, I view stocks as a reasonably good relative value.

Furthermore, using a valuation metric made popular by Yale economist Robert Shiller, stock valuations appear modestly higher than the historical average (for consistency, I start the average in 1926; his data goes back to the 1800s). That means that while stocks aren’t resoundingly cheap like they were in the early 1980’s, they aren’t outrageously expensive either, like in 1999.

As difficult as it is to ignore the headlines, it is still important to remember the fundamentals: stocks are riskier but should provide higher returns, bonds are a stabilizing force in a portfolio, and investors should maintain a long term time horizon and stick with the plan that has the highest probability of meeting their financial objectives.

These theories are at the heart of capitalism. The system still works and I’m still a capitalist.