As you might hope and expect, we are constantly looking for ways to improve returns, reduce risk, or in a perfect world, both. That means that we are always looking at strategies, evaluating their pros and cons and trying to figure out whether they are better than we are currently doing.

One interesting strategy that we’ve looked at over the years that is simple to understand is to buy the stocks in the S&P 500 in equal proportions. The index that we all know and love is called market-cap weighted, which means that the size of the company determines the weight in the index.

Right now, the largest company in the S&P 500 is worth about $725 billion. If you add up the value of all the companies in the index and divide the largest company by the total value, the largest company is worth four percent.

Even though these market cap weighted indexes have performed marvelously compared to actively managed stock portfolios, critics argue that they have their own problems, most notably that when a company is overvalued, you get more exposure to it – exactly the opposite of what you want.

If instead of market cap weighting, you simply bought equal proportions of all of the stocks in the index, you would have an identical weight to all of the stocks regardless of whether they are over or undervalued.

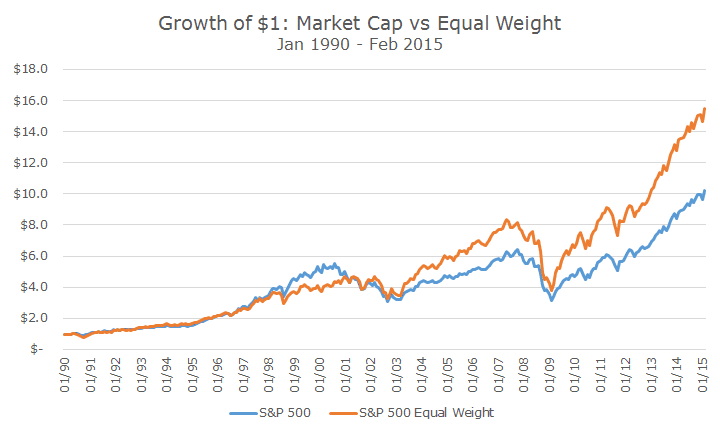

At first blush, the results are pretty good: S&P created an equal weight index that dates back to 1990 and the equal weight index has earned an annualized return of 11.5 percent compared to the traditional market-cap weighted index, which earned 9.6 percent over the same time frame.

In the chart above, notice how the equal weight index underperforms during the tech bubble of the late 1990s – it’s not getting over exposed to the tech stocks that propelled the market to unsustainable heights.

In the past five years, the equal weight index has performed wonderfully, easily beating the traditional index.

I decided to test the equal weighting against my favorite market exposures that you’ve come to know and love: value, momentum, size and quality.

It turns out that equal weighting is nothing more than a combination of these strategies, most notably size and value. To use some fancy jargon, there is no alpha in an equal weight strategy, just different market exposures, most notably size and value.

If you think about it, that makes perfect sense: equally weighting the holdings gives identical exposure to the largest company and the smallest company, so it overweights the small guys and underweights the large ones.

The same is true for value stocks – the cheap ones that have been beaten down in price get the same weight that the overvalued ones do, so there’s more exposure to cheap stocks than the conventional market weight average.

Since there is no special sauce, you can create the same exposure just by tilting towards size and value. There is nothing particularly wrong with equal weight, except that you can do the same in cheaper products. You’re also missing out on momentum, which has historically added a lot of value.

Even though we look at a lot of strategies, it’s hard to find something that’s both worthwhile and truly original. There are a lot of different approaches and if you don’t know what you’re doing, they look unique, but, for the most part, they all boil down to the same thing, just dressed up differently.

For a fascinating look at originality, check out this series of podcasts from the TED Radio Hour on NPR. It may not be original, but it’s terrific.

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott