Looking back at the year that was in 2013, one of the most interesting questions in my opinion is which style won: growth or value? Before answering the question, let’s take a quick minute to discuss these two styles.

In short, value is the tendency for cheap stocks to outperform expensive stocks. Simple enough, right? It sounds like something legendary investor Ben Graham or his prodigious student Warren Buffet might say.

Decades after Graham and Buffett, the academics agreed. In 1977, an academic named Basu (I can only find his first initial, ‘s’) wrote in the Journal of Finance that stocks with low price-earnings ratios tend to outperform stocks with high price-earnings ratios (cheap outperforms expensive).

Basu’s study and subsequent work by recent Nobel Prize Laureate Gene Fama and his buddy Ken French, found similar results whether you looked at price-to-earnings, price-to-book, price-to-sales or price to cash-to-cash flow ratios; or, more simply price-to-some-fundamental-measure.

When Fama et all determined this, they sorted stocks each year into three categories: cheap, neutral or expensive. Sadly, though, they named these groups, value, neutral and growth, creating some of the most confusing and misunderstood terms in finance.

I say misunderstood because the studies show that value is GOOD and growth is BAD. Growth sounds good though – after all, don’t we want our investments to grow?

Fama and French were trying to say that these expensive stocks happened to be ones that were growing more quickly as businesses than the overall market, but investors were paying so much for these fast-growers that the investments underperformed.

But think about it – for one style to outperform systematically, another one has to underperform by the same amount. You can’t have two separate, systematic styles both outperform since investment returns from year to year are, in the aggregate, are a zero-sum gain.

Said another, way, ff the market ‘average’ is ten percent, for something to earn 11 percent, something else has to earn nine percent. As another Nobel Prize winner, Bill Sharpe says, ‘it’s not theory, it’s arithmetic.’

To make matters more confusing, the investment industry co-opted these already bad terms and created products that eschewed the benefits of both styles even though only value delivers over the long run.

All of the index providers have bastardized the growth and value definitions so that growth wins half the time and value wins half the time – and both are watered down so that neither wins by very large amounts. Why? I think so that they can license the most indexes to mutual funds and ETF providers. Why sell one index, when people want to buy three?

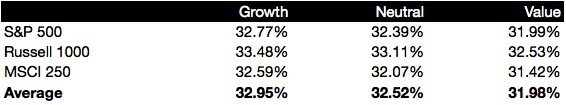

Ok, back to the short run – last year. The table below shows the large cap returns for growth, neutral and value indexes by the largest three index providers.

When I look at the data, I mainly see returns that are indistinguishable from each other – although growth does win by an average of 42 basis points against the neutral index and value loses by (surprise!) about the same amount.

So, this seems like a lot of set up to answer the original question, who won, value or growth? That’s because the value fund that we use, which is based on the academic research is was up more than 40 percent last year. (I can’t name names since its on our Approved List)

An ETF that we don’t use but is constructed similarly, the Guggenheim S&P 500 Pure Value (RPV) was up an astonishing 47.5 percent.

What is all this telling you? The value premium that is written about in academia isn’t captured by very many funds because the index providers water down their products to make them more accessible to more investors.

When the academics release their research data in a few months, I will be able to test this more rigorously, but the differences are so large, I know what I am going to find – value won in markets and for our clients, but not for most investors.