When I was in college, I read Liar’s Poker, by Michael Lewis. It’s the true story of Lewis’ job out of college on the trading floor at Soloman Brothers, the most powerful bond trading firm in the world at that time.

Many of the characters like John Meriwether, Lewis Reneri, and John Thain are still staples of the financial media, but no one became more famous than Lewis himself.

He’s gone on to write several mainstream books that also went on to become movies, most notably Moneyball, The Blindside, and The Big Short.

I love Lewis’ books, so I was irate when he went on 60 Minutes in 2014 and told the world that the market was ‘rigged’ against them. He was promoting his new book at the time, Flash Boys, which was devoted to stories about electronic trading.

There was nothing particularly new in Flash Boys, but the micro-structure of markets isn’t widely followed, so it seemed new. The thrust of Lewis’ message was that savvy traders that have powerful computers steal a little bit of money from every transaction.

As I said, there is nothing new about that – market makers have been doing that since trading was under ‘The Buttonwood Tree,’ before there was an exchange. Even as late as when I joined the business, there was a type of trader known as a scalper.

The scalpers are gone, and the computing power behind this type of trading is impressive. But, the market is not rigged.

After reading the book, I decided to hire a firm to analyze our trading to prove that the market wasn’t rigged. I figured that we were losing a little money to the market, known as implied transactions cost, but I didn’t think it was very much.

Now, I have five years of data that demonstrate that the market isn’t rigged.

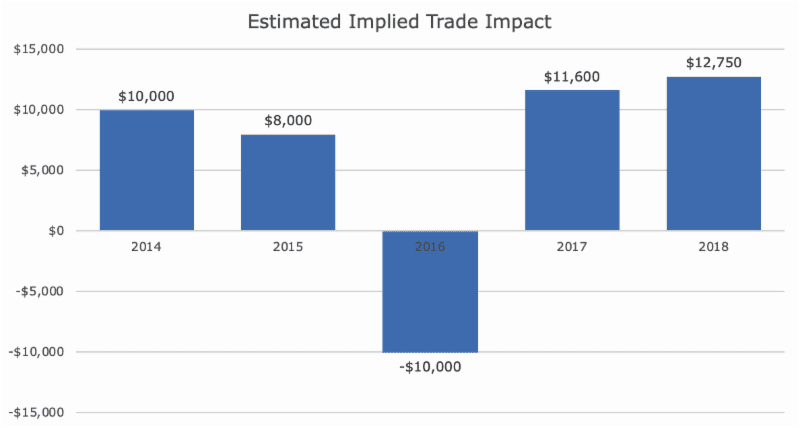

The first chart shows the estimated implied market impact of our trading, which is what the market maker or scalper (electronic or otherwise) made from our trades by pushing the market around.

For example, let’s say that ABC is trading with a bid/offer of 99.98/100, which means that we can buy ABC at 100 or sell it at 99.98, and the market maker will make 0.02. If a market maker sees a big imbalance, like a pension making a very large purchase, the market maker may raise the price to 99.99/100.01.

As soon as the pension is done buying, the market maker lowers the price back to 99.98/100. The market maker just scalped a penny one a big ticket and made a few bucks.

You can see that while the market did make money on us four out of five years, the dollar amount is extremely low. We should assume that the market will make money on us, and I find it surprising that we extracted $10,000 of profits out of the market in 2016 (although I’m not complaining).

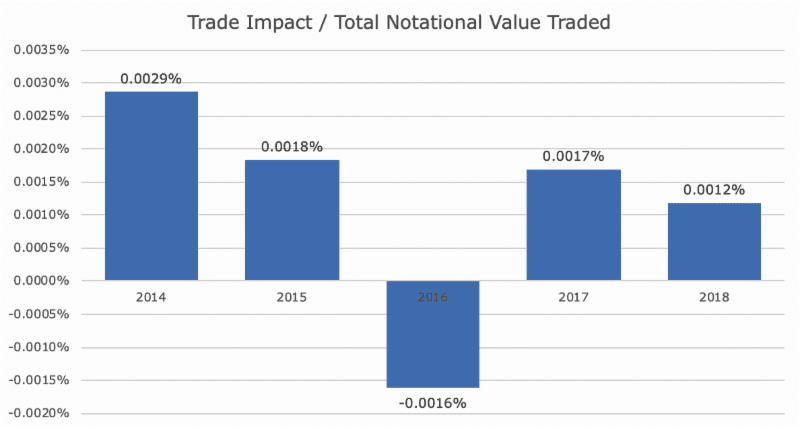

Here’s a chart that shows the same thing, but divided by the total dollars that we traded.

I find this chart amazing because it’s showing that the market impact is getting smaller over time. In 2018, our estimated implied transaction cost was one-twelfth of one-hundredth of one percent. Pretty tiny!

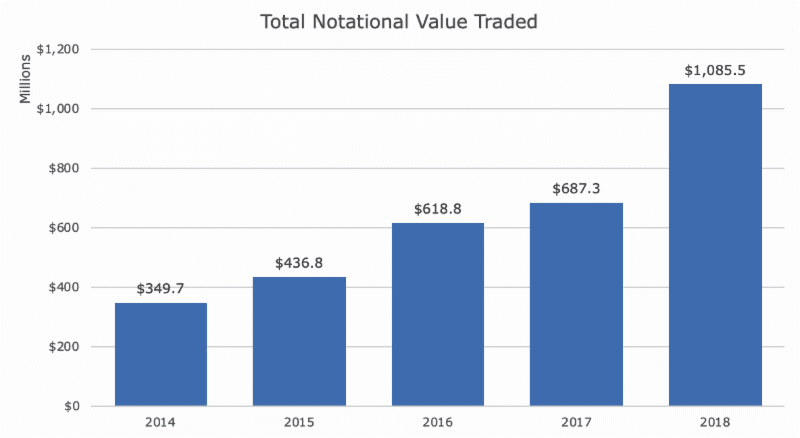

To understand just how impressive that is, you have to know how much we’re trading, which can be seen here:

I want to be clear that we are not active traders – clients sometimes ask us why we don’t trade more! Most of what’s traded is related to client deposits and withdrawals, humdrum re-balancing and tax loss harvesting.

The spike in 2018 is definitely attributed to some not so humdrum re-balancing and tax-loss harvesting – about a third of the trading last year was done in December when the market sold off.

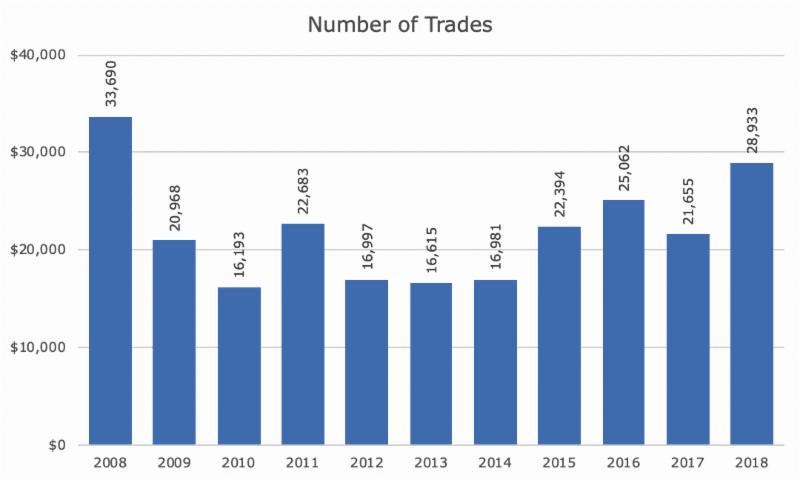

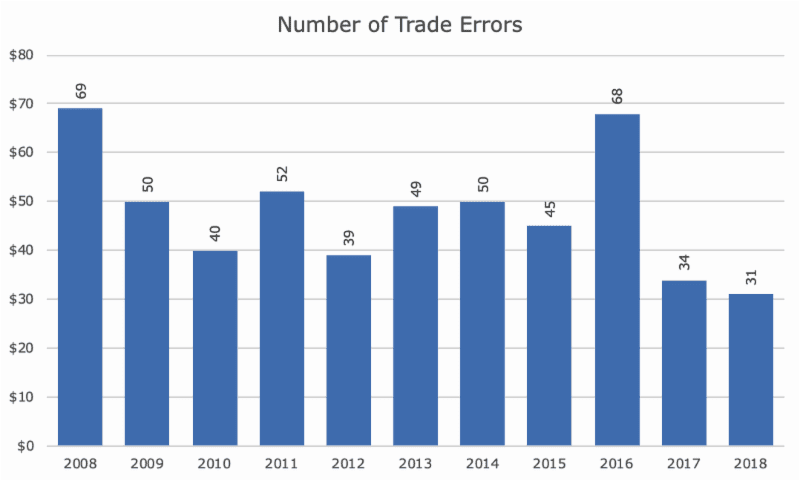

I also like to look at the simple number of trades that we execute.

These trades are executed solely by four people at Acropolis: Minjung Son, Tim Side, Seongpil Hong and Ryan Craft. It’s remarkable that so few people can be so productive and get every dollar in the right account at the right time.

Well, they do make some errors, but I’m only telling you because I’m proud of how few errors they make.

And, you should know that when we do make errors, that we calculate whether you’re better or worse off from the error. If you’re better off, you get to keep the gains, and if you’re worse off, we eat them (unless they’re less than $100, in which case the custodian usually pays).

I should note too, that the traders aren’t responsible for all of the errors – sometimes is the (gasp) Portfolio Manager or Portfolio Administrator.

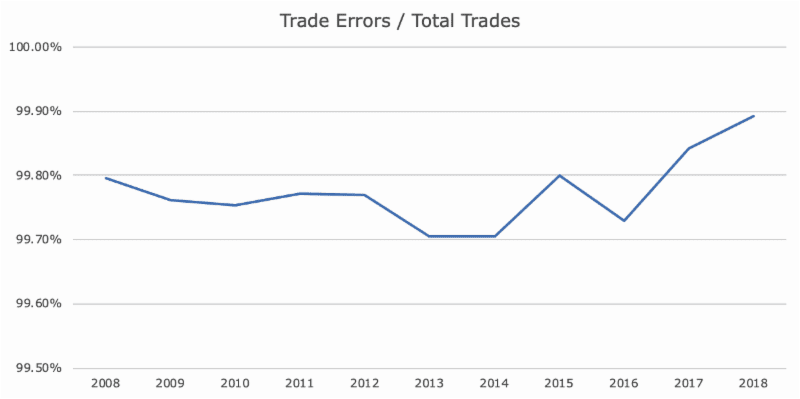

Yes, there hasn’t been a year yet where we made 75 errors. Remarkable, especially when you consider the number of trades that we execute, as pictured above. Still, I thought I would highlight it by showing the percentage of trades that we get right, and you can see that we’re a well-oiled machine, just shy of 99.9 parent of trades completed without error.

Now that you’ve gotten to the bottom, I hope that four things stand out.

First, we take trading seriously. All firms are required to try and get what’s called ‘best execution,’ but I don’t know of a single other Registered Investment Advisor that hires an outside firm to estimate trading costs.

Second, the market isn’t rigged. Or, if it is rigged, we’re protecting you from it. I don’t think that’s the case, I don’t think it’s rigged. But trading does require a constant eye because, if you’re not careful, the implied trading costs could be a lot higher.

Third, we have a very talented group of traders that do an excellent job of executing all of the orders that come through with almost no errors. And that’s just their day job – all of them are key, voting members of the Investment Committee that work on asset allocation, security selection, and all of the things that go into a building a portfolio.

Lastly, there’s a lot that goes on behind the scenes at Acropolis. In a way, I don’t want clients to think about all of the details that are vital to our operation because most people hire us so that they don’t have to think about this stuff.

But, at the same time, I still want people to know that it happens continuously, and successfully (even in a snowstorm).