Companies’ capital decisions aren’t usually very controversial, like paying down debt, paying another quarterly dividend, or upgrading the facilities.

Stock buybacks, however, are another story: they generate a lot of controversy. Before getting into the debate, let me take a minute to describe a buyback.

When companies have extra capital, they sometimes go into the open market and buy back their own stock, hence the name (although they are sometimes also called share repurchases, but you get the idea).

When a company buys back its shares, it reduces the number of shares outstanding, which increases the ownership percentage of the other shareholders. It also increases the earnings per share because the same profits get distributed across fewer shares.

That hardly seems controversial, but critics argue that buybacks boost a company’s stock in the short term at the expense of long-term investment.

In other words, a management team that is compensated based on the share price over the next year might opt for a buyback even if the company might be better off in the long run if it puts more money into research and development or employee training.

But that’s also true with cash dividends, which hardly generate a lot of heat.

The difference here often boils down to politics. Proponents of buybacks like them because they are a tax-efficient way to return cash to shareholders because, until recently, buybacks weren’t taxed.

That also makes buybacks unpopular with critics, who say that companies are cheating the government (and, therefore, the people) out of tax revenue that they would pay with dividends.

Personally, I’m okay with buyback because I want companies to return capital to shareholders, and I prefer less taxes to more. I don’t want to debate tax policy, but I always thought dividends were unfairly taxed because the company pays tax on the profits, and then shareholders have to pay tax when the profits are distributed to the shareholders.

I also think some of the critiques of buybacks are true, but for every example of bad use of buybacks (I’m looking at you, General Electric), I think there are good examples too.

That said, I don’t think investing more heavily in companies buying back their stock is more important than companies that aren’t.

I analyzed the S&P 500 Buyback index, which equally weights the 100 stocks in the S&P 500 with the largest stock buyback programs. The summary statistics appear remarkably good at first blush, but further analysis suggests they aren’t as special as they first appear.

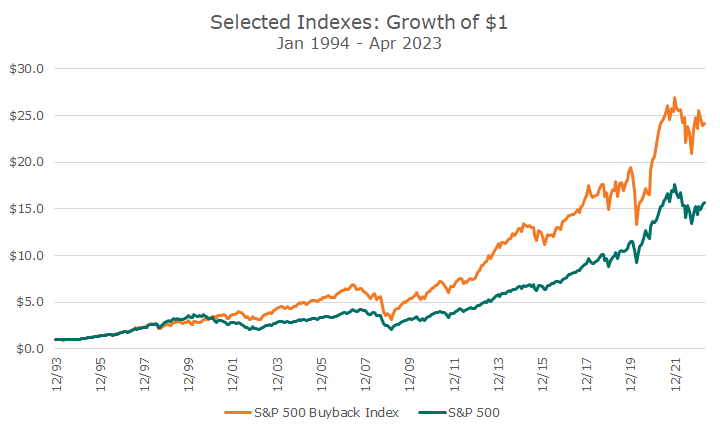

The annualized return for the S&P 500 Buyback Index has been 11.5 percent since its inception in 1994, which is 1.6 percent better than the S&P 500’s 9.9 percent annualized return over the same period. The volatility for the buyback index is higher, but not by a lot.

That kind of outperformance for many years makes the buyback index look pretty amazing.

Whenever I compare two indexes, I always look at the growth of the index I’m interested in (the buyback index in this case) compared to the growth of the benchmark index. In the chart above, the growth of the overall market dominates the chart and somewhat distorts the image.

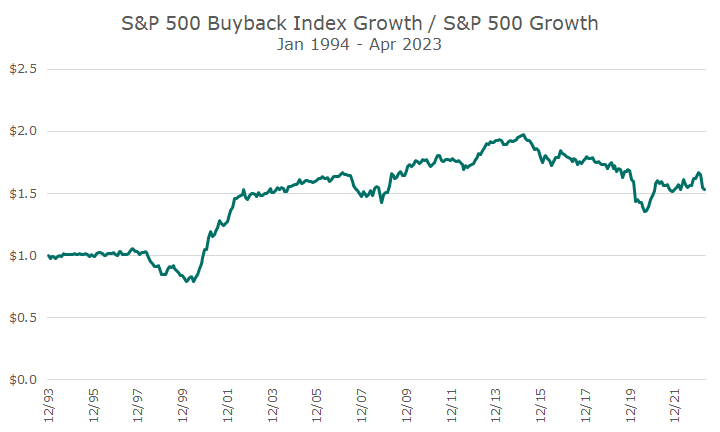

By removing the market’s impact, we can see four distinct phases for the outperformance of the buyback index. The first phase, in the 1990s, shows the results were essentially the same.

The buyback index underperformed slightly in the late 1990s, but that leads to the second phase when there is a sharp period of outperformance of the buyback index that lasted for two years.

The buyback index steadily outperforms until about 2014, reversing course and underperforming until recently. You can say that all of the outperformance occurred in a two-year period about 20 years ago, which is hardly a compelling investment case.

I also ran the data through a test that breaks down the performance into well-known academic factors to see whether there is something special in the buyback index (alpha) or whether we can achieve the same results another way.

Perhaps not surprisingly, there is no remarkable return associated with buybacks – no alpha. Instead, we see a strong weight to the value factor (cheap versus expensive stocks) and a very strong weight to the quality factor (high-quality companies versus junky ones).

The high-quality exposure makes sense since these are the 100 companies that are returning the most money to shareholders in the form of buybacks, and junky companies can’t afford to do that.

I always find it reassuring when I look for something special and don’t find it. It reaffirms my view that, at the end of the day, we know what drives markets over the long run – high-quality companies at attractive valuations that are moving higher, otherwise known as quality, value, and momentum.

Despite all the noise around them, the strong results related to buybacks are simply another way to configure the fundamentals we already understand.