Last week, I promised to discuss the odds of entering a recession in more depth and suggested that a financial crisis is less likely this time (but you never know). If you missed it, you can read it here.

I also referenced a talk I saw by local Fed official Bill Emmons, who highlighted the possibility of a recession in 2018. He wasn’t right about that (well, he only said the risk was higher than you think, so he wasn’t exactly wrong).

Still, I like the framework that he laid out that recessions broadly fall into three categories: over-expansion, tightening financial conditions, and coming from out of left field. Last week, I categorized the recessions since the 1960s into one of those three groups.

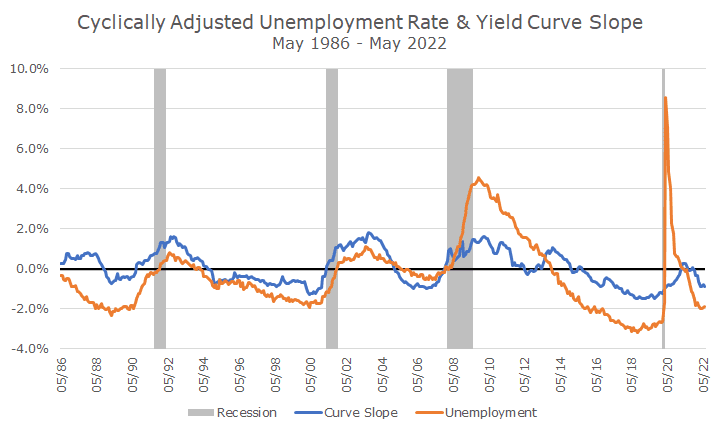

As I reread my old articles, I thought it would be interesting to update the data points he laid out at the time. It was a simple model with two variables: a cyclically adjusted measure of unemployment and a cyclically-adjusted measure of financial conditions based on the slope of the yield curve.

I didn’t realize it then, but when we said cyclically adjusted, he just meant the current level compared to the last ten years. So, in the unemployment signal, the first step is to look at the average level of unemployment over the last decade, which was 5.5 percent. Then, we compare the current level of 3.6 percent to the average, and we can say that unemployment is very low in this cycle.

It’s been long enough that I couldn’t quite replicate the work I’d done before, but since there aren’t Ph.D. economists reading this, I think it’s okay.

The first chart shows each of the two signals independently, with the slope of the yield curve in blue and the unemployment situation in orange.

Broadly speaking, you can see that there are cycles where the values are higher right after a recession and fall as time passes, only to rise during a recession. You can also see just how crazy the pandemic was with the massive spike in unemployment and relatively quick recovery.

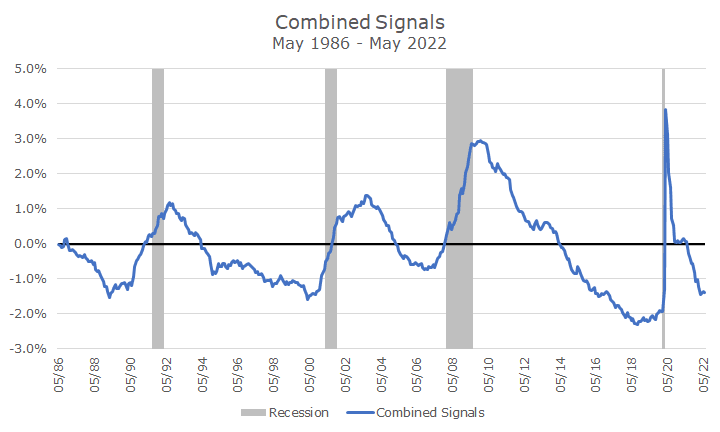

In the Emmons presentation, he combined the two signals, which I’m showing here. It shows the same thing but is a little easier to read (though maybe no more informative).

I’m not sure Emmons would want anyone to put too much into his back-of-the-envelope model, but I think it’s reasonable at a very high level.

And my reading of the charts is that you can see a little deterioration in the signals (individually or together) before a recession, meaning that the downtrend bottoms out and starts to trend higher.

That said, there are only four recessions to look at with this data, which is a very small sample size. And my hairy eyeball analysis suggests that the time between bottoming and entering a recession varies, which is bad when you have a small sample size.

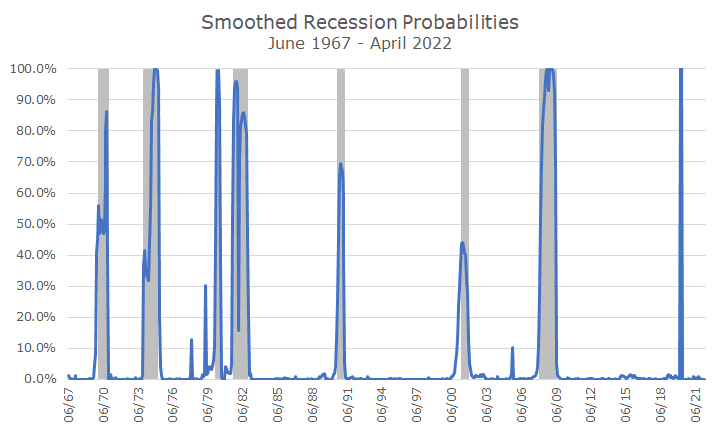

In other words, this may tell you something, but it may not. But, I found a model on the St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED database website that tries to estimate whether the economy is in a recession.

I’m sure that Ph.D.’s fight about this one a lot, but there’s a problem: the ‘right now’ is as of April. It also appears that there isn’t much warning signal. I read about a New York Federal Reserve model that tries to predict the odds of a recession in the next 12 months, but I couldn’t find the data (the article said four percent).

Looking at the chart below, the signals they used to create their model aren’t designed to forecast a recession; they only tell you whether you’re in a recession right now. I would say that it does that, but it doesn’t answer the question about whether we may go into recession.

Just because these two models don’t forecast recessions perfectly doesn’t mean that no models work at all. But, if trained, professional economists can’t agree, it makes sense that no single model exists.

So, I’ll go back to my statement last week: there will be a recession, but we don’t know when. I’d bet on one in the next year, but that’s not much of a bet since the stock market appears to be saying the same thing. It doesn’t help to know that there’s a good shot that we’ll enter a recession if everyone else already knows that and it’s built into stock prices.

Moreover, even if we could say that there would certainly be a recession in the next year, we still don’t know how long it would last or how deep it might cut. It’s hard enough just to say that we’re likely to enter one in the not-too-distant future.

The good news is that stocks and bonds have always rewarded investors in the past who had the appropriate time horizon. And our planning is designed to find the right mix for you specifically. Recessions are part of the normal economic cycle, just like the nighttime is to the day and the winter is to the year.

That doesn’t mean that it’s easy to live through. Like most things worthwhile, it’s easier said than done.