There are a handful of annual outlooks that I look forward to each year, and one of them is Vanguard’s Economic and Market Outlook.

The report, which you can find here, is thoughtful, thorough, and isn’t trying to sell you anything (which is high praise in this industry). They also have great titles, and this year’s was a standout: A Return to Sound Money.

In their opening paragraph, the authors say that the return to sound money is “the single best economic and financial development in the last 20 years.” Wow!

Usually, when I hear the phrase sound money, it’s from gold bugs that want to go back to the gold standard. In this case, Vanguard defines sound money as “the persistence of positive real interest rates.”

If they explicitly defined real interest rates, I missed it, perhaps because the report is 24-pages long and has plenty of footnotes.

In general, I know what they mean, that nominal interest rates are higher than inflation. But specifically, it would have been nice to see what interest rate and which inflation measure.

I would have also been interested to see the history of sound and unsound money over time.

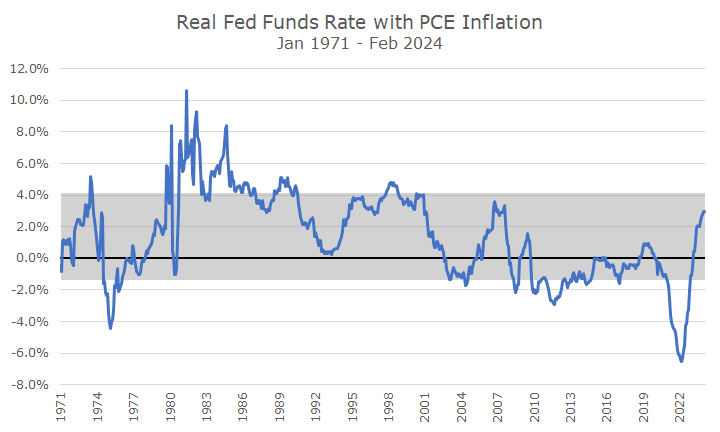

So, I took matters into my own hands, for better or for worse, and found an index that I thought made sense and plotted it below to see what it’s looked like over time.

In this chart, the interest rate is the Fed Funds rate, which is the interest rate that depository institutions (like banks) lend their reserve balances to other depository inductions overnight. When we talk about the Fed hiking or cutting rates, this is the one that we’re talking about.

The inflation rate in this chart is the Personal Consumption Expenditure, or PCE, which is a broad measure of inflation that the Federal Reserve targets at two percent.

The blue line is simply the Fed Funds rate minus PCE inflation, and the gray band is my attempt to show what’s “normal” since 1971, when this index started. The black line is zero, marking when real rates are either positive or negative.

You can see that the real rate was pretty negative in the mid 1970s, when inflation was out of control, and then the real rate was outrageously high in the early 1980s when then Fed Chair Paul Volker jacked up rates to kill the high inflation.

Although most folks complain about their high mortgages at the time, it was a great time to be a depositor.

Real rates fluctuated for the next 15 years but were positive. Then, after the tech bubble burst and 9/11 happened, the Fed took rates very low to the point that real rates were negative.

It was meant to be a short-term effort, and it was, but when the 2008 financial crisis came around, they took real rates negative, and they stayed there for the next decade.

Low interest rates and an inflation shock following the pandemic, took real rates to the lowest point of this index, but when the Fed raised rates and inflation subsided, real rates turned positive, which is where we stand now.

The good news about higher real rates, or the return of sound money as Vanguard put it, is that savers will finally get a real return on their cash, and capital will be allocated more appropriately with less speculation (although with Bitcoin near $70,000, that hasn’t taken hold just yet).

Higher real rates will limit borrowing and increase the cost of capital, and encourage savings, but it also puts more strain on governments that spend more than they take in (do you know of such a government?).

I agree that the return to sound money is incredibly important (and not just because unsound money sounds pretty lousy). They are clear to point out, and I agree, that while it is good for long-term expected returns (especially for bonds), it’s a transition that won’t be easy, and we should expect market volatility.