The volatility last week was startling. The S&P 500 was up 2.99 percent on Wednesday but then fell -3.56 on Thursday.

It was just as startling as the week before, when the S&P 500 rose 2.47 percent on Thursday, only to fall by -3.63 percent on Friday. Or the week before that, when stocks rose 1.61 percent on Tuesday and fell -1.48 percent on Thursday and -2.77 percent on Friday.

There is no doubt that the stock market has been a roller-coaster ride for the past five weeks.

And, there isn’t a sense that it’s almost over. On the contrary, many of the underlying uncertainties are still unanswered. How far and fast will the Fed raise rates? When will inflation peak and how high will it go? When will the supply chain constraints ease? What is Putin going to do next? How far will stocks fall? I think it’s anxiety-provoking.

At the same time, it’s also not uncommon. Intellectually, we all understand that to earn a big reward, you have to take risks. But that doesn’t make it easy to get through the tough times when they come along.

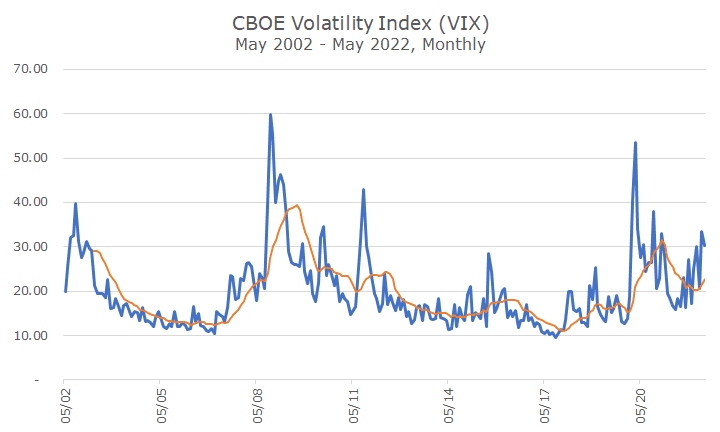

Let’s take look at a measure of volatility for the S&P 500. It’s actually a measure of expected volatility, but it tells you a little more about where markets think prices are going, rather than where they’ve been.

I’ve plotted the monthly numbers dating back to the start of the index in 2002 and used Friday’s price for this May (and a lot can happen in either direction by the end of the month). I also added a one-year moving average to take some of the ‘noise’ out of the chart.

The big spikes center around the big events of the last 20 years. First, you can see the dot-com bubble bursting, then the 2008 financial crisis, the pandemic, and the current period.

In my view, the current period is part of the pandemic. Although the virus itself has died down, the inflation that we are dealing with was borne out of a mix of the government response to the pandemic and the supply chain issues that resulted. We had a quiet period, but you can see that happened in the 2008 crisis that lasted a few years.

I think if the VIX data went all the way back to the 1920s like the total return data, we’d see the same thing over and over. Long periods of relative calm with bursts of volatility. That’s what makes me call this volatility ‘normal.’ Even though it’s no fun, we all know it’s part of the process.

The good news is that almost everyone reading this has bought into the buy-and-hold approach that we employ. Some people have a nagging urge to bail out, but I can tell you from the previous volatility spikes that the folks that bailed were no happier after they did – they mostly worried about when to get back in.

That’s why we set the allocation at the start in a written Investment Policy Statement (IPS) that highlights how bad things got in previous periods. We want everyone to do a ‘gut check’ when we show them the potential losses in percentage and dollar terms.

We know that investors would prefer a strategy that buys at the bottom and sells at the top, but no one can do it, so we set an allocation that matches their risk tolerance. As a result, we don’t get as much of the upside, but we don’t get as much of the downside.

When markets are rising, people naturally want more risk, and when they’re falling, they naturally want less. Among our most important roles as advisors is finding the right allocation for each client, mostly defined by their risk tolerance and financial picture, and then sticking to it in times like these.

As the founder of Vanguard, Jack Bogle, famously said: the optimal allocation is the one that you can stick with.

Although we don’t know how far markets may fall, we know that they will hit a bottom and then recover. Well, they always have in the past, and we assume that will be the case in the future.

And it makes sense that they would: stocks are ownership stakes in businesses, and we expect them to continue to be profitable. Not all companies or all of the time, but on average and over time.

So, it’s a hard message after five weeks of losses, but sit tight and hold on, we’ll get through this.