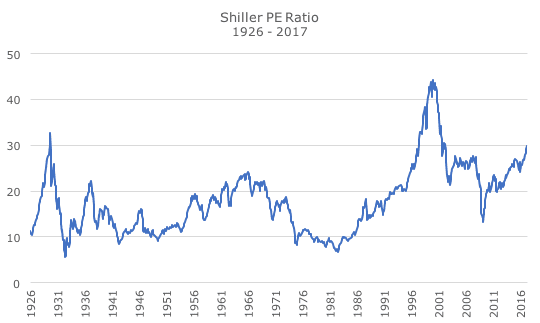

The stock market since the election has brought all of the major indexes to fresh all-time highs. I also noticed last week that the Shiller PE ratio is about to cross 30, which is far from an all-time high, but is still notable since the only two times in history this ratio has been so high was in the Roaring 20s and during the Tech Bubble.

For those of you that may not remember the Shiller PE ratio, it’s like a normal price-earnings measure except that it uses a 10-year average earnings rate adjusted for inflation. Invented by famed investor Ben Graham, the idea is to look at average earnings over long periods to smooth out the effects of the business cycle.

Graham used the measure when evaluating individual stocks, but it was economist Robert Shiller of Yale that popularized the metric for the whole S&P 500. He thought that the market was in a bubble in the late 1990s and this metric served as one of his primary arguments. When the bubble burst, he was credited for calling it correctly and so what was once Graham’s became the Shiller PE.

Outside of the 1920s, the Shiller PE mostly ranged between 10 and 20 until the 1990s. That bubble is pretty easy to see in retrospect, but what I find more interesting is that outside of the 2008 financial crisis, the Shiller PE ratio has ranged between 20 and 30 since the tech wreck. Now, though, it looks like we could trade out of that range to the upside.

If we do trade materially above 30 for a sustained period, what does that mean for investors? To be perfectly honest, I’m not totally sure.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, there have been a lot of technical arguments for why the Shiller PE should trade at higher than average levels from accounting issues to the low interest rate environment. It’s hard to know whether those arguments are right or just excuses that will look obviously wrong in retrospect.

What should investors do about the high Shiller PE ratio? First and foremost, I think investors should make sure that they are comfortable with their allocation to stocks. We have data that shows how much stocks have lost in the past; and while past performance isn’t necessarily indicative of future performance, it’s a fine starting place (that’s not just a lawyerly statement – it’s totally true).

Second, I think investors should keep a reasonable portion of their stock portfolio in foreign stocks. If you’re an Acropolis client, you’re already doing that (if you’re not a client, you should become one!). Shiller PE ratios are much lower for developed and emerging market stocks, which makes sense given how much the US has outperformed non-US stocks over the last five years.

Third, investors should avoid the temptation to time the market. Even though Shiller should get a lot of credit for calling the tech bubble, I wouldn’t say that he called it accurately – he made his case in 1996, four years before the bubble burst. During that time, the S&P 500 doubled in value. In 2008, he said he would wait until his beloved ratio fell below 10 to buy. It never did and he missed out on the subsequent rally.

Lastly, I think investors should keep their expectations in check. My thought, which I wholly recognized as incomplete, is that we should expect lower returns in the coming years than we’ve experienced in the past. It seems to me, quite simply, that if you pay higher than average prices for assets, you should expect lower than average returns. The opposite is true as well; if you pay lower than average prices for assets, you should expect higher than average returns.

It’s not a bold world view, but I think it sums up how we should think about overall market valuations. And if your time horizon is sufficiently long (and your time horizon is probably longer than you give it credit for) you really don’t have to worry much about any of this. If you didn’t read it last week, check out this American pick-me-up from Warren Buffet.