Over the past few months, markets and investors were worried about the possibility of inflation coming back.

And, there was and is good reason for concern: the economy is rebounding quickly, finding examples of labor shortages is easy, there is still massive monetary stimulus in place, and there are discussions of even more fiscal stimulus to come.

I’ve personally been a little bit skeptical, mostly because I remember all of the discussion about inflation following the massive stimulus in 2008 that never arrived. That said, this recession is pretty different since it was based on a pandemic rather than a financial crisis.

In recent weeks, the bond market has shifted gears, and interest rates have been falling, potentially telling us something about what the bond market thinks about inflation.

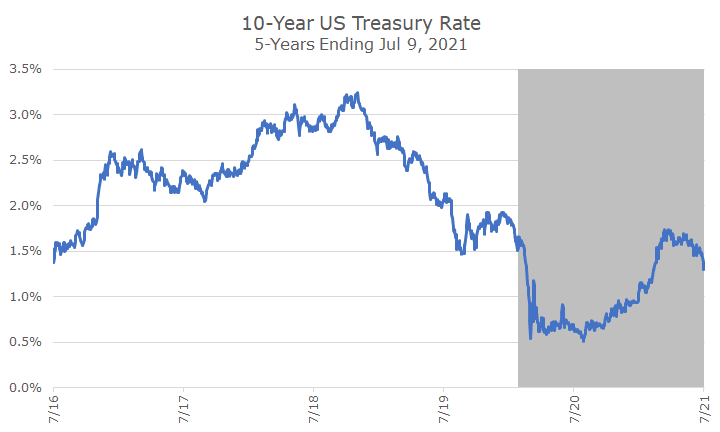

The chart below shows the rate for the bellwether 10-year US Treasury over the past five years. Prior to the pandemic-induced recession, which is marked in gray, yields were bouncing between 1-5 and 3.0 percent but were trending lower when the pandemic arrived.

When policymakers got into action and cut short-term interest rates, the 10-year yield followed suit. And the yield then hung around a half of a percent for nearly a year while we all sheltered-in-place.

Then, when it became apparent that we had some vaccines and that the economy would reopen in the relatively near future, yields started to tick higher. The speed of the increase got a little concerning because it suggested that the pickup wasn’t just about returning to normal, but about higher than expected inflation.

In recent weeks, though, the yield has fallen off some, particularly last week, when it got down to 1.25 percent (although it didn’t end there).

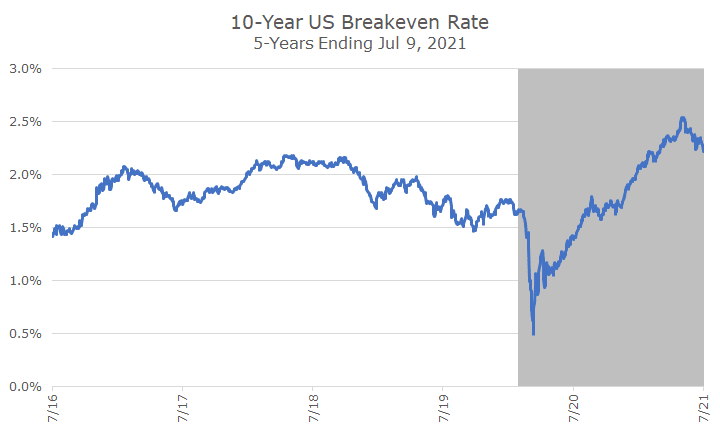

The chart below shows the ‘breakeven rate,’ which is the difference between the yield on the 10-year US Treasury and the yield on the 10-Year US Treasury Inflation-Protected (TIP) bond.

While the 10-Year Treasury yield contains information about inflation expectations, there are other factors as well, so the breakeven is helpful because it isolates the inflation expectations.

Just like the first chart, we can see that before the pandemic, inflation expectations over a 10-year horizon floated between 1.5 and 2.0 percent.

When the pandemic hit, inflation expectations fell dramatically but started to pick up relatively quickly, and it wasn’t long before they outpaced the pre-pandemic levels.

But we can see also, that in recent weeks, that inflation expectations over the next 10-years have softened some, which is a welcome view. It’s also worth noting, however, that at their worst, the breakeven inflation rates didn’t signal more than 2.5 percent of inflation over the next decade.

Even though that’s higher than what we’ve experienced over the last decade, it still well below the three percent assumption that we use in our financial planning model.

What’s driving the recent trend lower? Markets are expecting less stimulus for one. The Federal Reserve signaled last month that rates would likely go up in 2023, which was sooner than most people thought.

Fiscal stimulus expectations are lower too – the infrastructure bill is in question and even if something does go through, it will be trillions lower than what was initially pushed for.

And, probably to a lesser extent, there is some concern about the impact of the delta variant, which could cause the reopening to slow down some.

Now, the question of whether the recent softening in expectations is a temporary pause in a march higher or the new baseline is an interesting question. It’s also impossible to answer.

Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal now expect core inflation, which excludes food and energy because they are so volatile, to come in at 3.2 percent in the fourth quarter, but fall to just over two percent in the coming years.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the 70 or so WSJ economists surveyed, expect inflation levels about like what the bond market expects. Sure, there are a handful that thinks it will come in higher and others who think lower, but on average, they think about what the market does, which makes sense since the market incorporated prices from all investors, not just 70 well-informed ones (who don’t have an incredible record at predictions, incidentally).

If they are right, and core inflation comes in between 2-2.5 percent over the coming decade, that will be relatively high versus the recent past. Since 1995, core inflation ran at just less than two percent.

So, you can still read a headline that says that economists expect higher inflation than we’ve seen in decades, which sounds pretty scary, but when you read the article and see the numbers, it should be a little less frightening.

At this point, there is no real indication that we’ll get 1970s style inflation, with persistent levels over 10 percent, but you never really know. I like to think that anything can happen but usually doesn’t.