A few days ago, I was listening to the podcast EconTalk (yes, that’s what I do in my ‘off’ time). The host, economist Russell Roberts interviews well known economists about a whole hos to economic subjects, from the broad theory to the day-to-day application.

The episode that I was listening to (but haven’t yet finished), featured Gene Fama, the University of Chicago Booth School of Business professor who came up with the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH) and recently won the Nobel Prize.

(A quick aside: one of the other Nobel Prize winners this year was economist Robert Shiller. He was interviewed in the Wall Street Journal yesterday and was asked, ‘Do you tell investors that they can pick winners … or do you tell them they’re not expert enough…?’ I loved his answer: ‘I tell people to get an investment advisor, that makes sense to me.’ My check is in the mail, Professor Shiller).

Back in the podcast, Roberts asked Fama how he got started and Fama said that when he was getting going in the early 1960s, computerized data analysis was just getting started. He and others were loading market returns into the room-sized punch-card computers to see if they could figure out ways to time the market.

They were hoping to find what’s called auto-correlation. We talk a lot about correlation, but when we do, it’s almost always cross-correlation, which refers to how two or more assets relate to each other. We know, for example, that the returns for stocks and bonds have almost no cross-correlation, which means that they work well together to diversify a portfolio.

Auto-correlation looks at whether the return of an asset from one period can tell you anything about the return for the asset in the next period. If something is has high-autocorrelation, then you can say that what’s happening today is likely to be good indication for what’s happening tomorrow.

Most investors know that that they can’t time the stock market, but when I ran this last summer while working on a project, I was surprised to see that bonds have equally low auto-correlation.

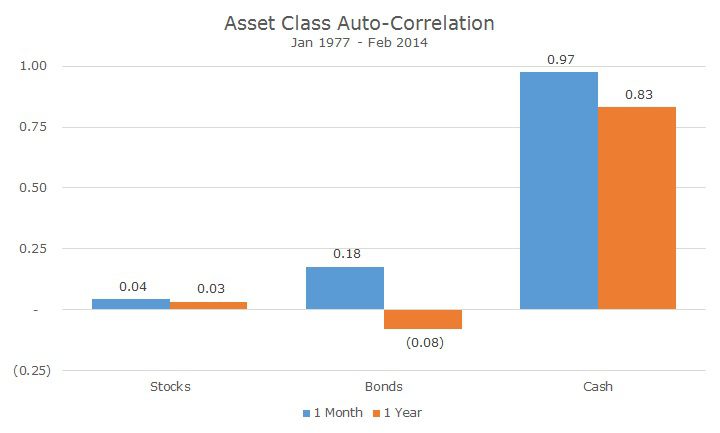

The chart above shows that the auto-correlation for stocks over a one-month period is 0.04, which is basically zero – the return from one month’s return tells you nothing about what will happen the next month. The same is true for the one-year period, where the auto-correlation is 0.03.

For bonds, there is a slightly higher autocorrelation from month-to-month at 0.18. That’s still so low that the information you have is really pretty weak, certainly not enough to trade on. Over the course of one-year, the autocorrelation goes negative, although it’s so close to zero that it basically means that you don’t have any information at all.

Cash is interesting because the autocorrelation is very high – on a month to month basis, it’s almost 1.0, which would be perfect correlation. This makes some intuitive sense since one-month rates are largely driven by monetary policy.

The bad news is that one-month Treasury bills pay nothing, so I can say with near certainty that they won’t pay anything next month either. The strength of the correlation drops somewhat over the course of a year, so I’m sorry (again) to report that rates will likely be very low on cash a year from now.

Most people seem to have accepted that they can’t time the stock market, mostly through their own experience with trial and error. While most investors say that they don’t understand bonds very well, their confidence about their own market timing abilities in the bond market seem higher to me.

Our strategy today does not involve attempting to time the bond market. Like most people, we assume that interest rates will rise in the coming years, but with a dose of humility, we recognize that we don’t really know. Even if that basic proposition is right, we still don’t know the timing or the magnitude, which means that we ultimately don’t have enough to trade on with any degree of confidence.

Thankfully, the buy and hold strategy that we use for stocks, applies to bonds as well. Bond returns have risks, just like stocks do, albeit with much less volatility.

Even cash, the least volatile asset class, has the risk that inflation will take away its purchasing power over time and right now, with cash yields as low as we are, the inflation risk of holding cash is unusually high.

Whenever you’re tempted to try and time the bond market, think of that auto-correlation chart and ask yourself whether you can really beat the odds that are stacked so highly against you.