Although the first exchange-traded-fund (ETF) hit the market in 1993, they really didn’t catch on until about 10 years ago. The first product ever is still one of the most popular, the Spider S&P 500 ETF Trust, which trades under the ticker SPY.

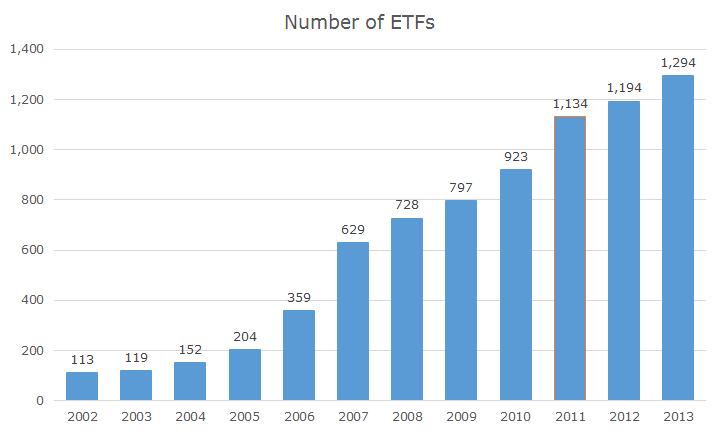

When we launched Acropolis in 2002 there were 113 ETFs on the market with a total of $102 billion in assets under management according to data from the Investment Company Institute.

As of 2013, there are 1,294 ETFs in the US with a total of $1.675 trillion in assets under management. Both the number of ETFs and the assets have grown by approximately 25 percent per year over the last dozen years. Not even the 2008 financial crisis could slow them down.

It makes sense – ETFs are attractive products. Their structure allows them to be more tax efficient than traditional mutual funds, you can buy or sell them during the trading day, unlike mutual funds and they are generally very low cost, partly because they were designed to compete with index mutual funds and cost was an important early differentiator.

Given the benefits that ETFs offer, it makes sense that they would grow significantly, although at this point, with so many products on the market, there is a lot of chaff in with the wheat. There are only so many ways that you can slice and dice the market, even when you include non-US stocks, bonds and a variety of asset classes.

Consider some of the extreme niche products on the market today

- An ETN that buys currencies that are currently pegged to the dollar.

- An ETF that tracks small cap stocks in Singapore

- An ETF that owns Chinese dividend paying stocks, except financials

- An ETF that buys diesel fuel and heating oil.

- AN ETF that shorts semiconductor stocks.

The list goes on and on. As a joke, someone once suggested an ETF that tracks Brazilian elevator operators, which I thought was pretty funny (nothing beats a good finance joke).

These goofy products don’t last forever, though; a lot are weeded out because they don’t attract enough assets to stay in business.

One of my favorite websites is called ETF Deathwatch and it maintains a list of ETFs that probably won’t make it because they haven’t caught on with investors (all five of my examples above were pulled from this list).

Consider the iPath US Treasury 5-Year Bull ETN with $500,000 in assets under management. It’s been on the market for three years and has performed comparably to the Barclays Aggregate bond index, albeit with a lot more volatility since it takes a leveraged bet that interest rates will fall.

The expense ratio is 0.75 percent, so the revenue should be about $3,750 a year, which surely means that they are underwater on the product. Unless something happens, management won’t want to fund that product forever.

An ETF liquidation is an unpleasant experience for taxable investors because the event effectively forces you to sell regardless of the tax consequences whether you want to or not.

Investors get the entire value of the ETF in a liquidation, so there is no special loss associated with the liquidation specifically, but the timing and tax consequences may not be favorable.

Although we’ve considered new ETFs, we generally wait for them to get established so that the risk of a liquidation is low. At one point, our clients owned more than five percent of an ETF and that was concerning.

Right now, our single largest reportable ETF holding (you don’t report mutual funds), valued at $63.5 million is just 0.28 percent of the total $22.9 billion ETF. (It’s funny, I say that we’re ‘just’ 0.28 percent of the fund because we’re the 35th largest holder. I wouldn’t have guessed we would be this ‘big.’)

Thankfully, keeping an eye on the ETF deathwatch is more of an academic exercise – where else can I get a list of crazy ideas? I think it would be fun to have an actual dead pool where people could wager on what ETFs will actually get liquidated next, but I suspect that’s a long time coming.