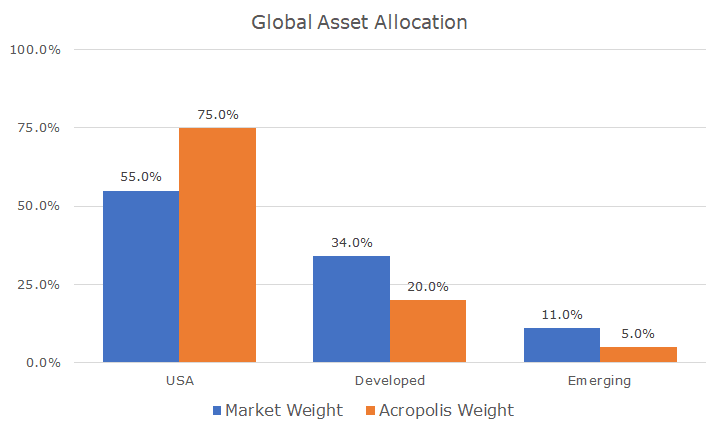

According to data from Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA), the value of the US stock market at year-end was worth $28.1 trillion – about 55 percent of the market value for all of the world’s stocks, which totals $51.2 trillion. Developed international stocks are worth $17.4 trillion in aggregate (34.0 percent), and emerging markets stocks are worth $5.7 trillion (11.0 percent).

In theory, passive investors should allocate their portfolio accordingly. In reality, almost no one does that, including Acropolis. We substantially overweight the US with a 75 percent allocation (of our equity allocation), put 20 percent into developed markets and five percent into emerging markets.

There are a lot of good reasons to have a “home country bias” like ours, but the question that I’ve been getting for the last few years is: why bother with international stocks? Shouldn’t we put all of our money into US stocks?

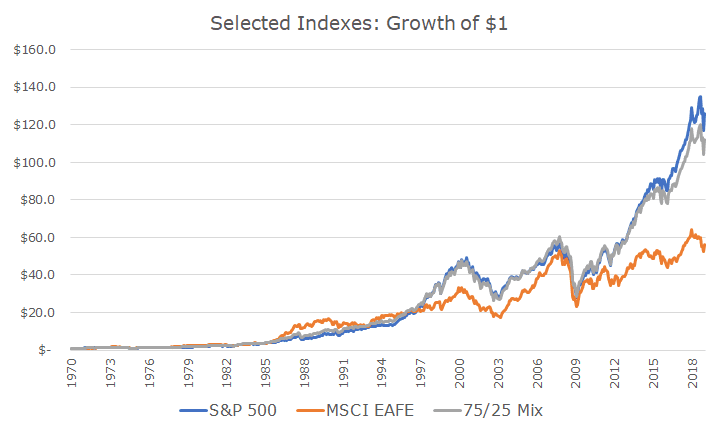

It’s easy to understand why people are asking: the performance of the S&P 500 has dominated developed and emerging market stocks for what feels like forever.

Over the last five years, for example, the S&P 500 has earned 10.96 percent through January 31st, while the MSCI EAFE index of developed market stocks has puttered along at 2.66 percent: only two percentage points better than one-month Treasury bills with 57x the volatility.

If you look back ten years, it seems better at first because the MSCI EAFE earned 8.11 percent – pretty respectable right? Maybe so, but not when compared to the S&P 500, which earned 15.00 percent during the same time. That means that a dollar invested in the S&P 500 10 years ago is now worth $4.05, while a dollar invested in the MSCI EAFE is only worth $2.18.

In fact, if you look today at the data that goes back to the inception of the MSCI in 1970, you might wonder why bother with international stocks: they’ve underperformed the S&P 500 by 1.81 percent per year and were about 10 percent more volatile.

The answer, as you may have already guessed, is diversification.

In my opinion, there are two ways to think about diversification. The first is pretty easy and is nothing more than the idea of not putting all of your eggs in one basket. If something terrible happens to the US, having some money in other markets could help. Of course, if something happens to the US, foreign markets will hurt too, but maybe less so.

I like to imagine what would have happened to my portfolio if I were Japanese. If you look at the summary statistics for the MSCI Japan index, they’ve earned about nine percent since 1970. The problem is that they earned all of that before 1990. Since then, the Japan index is only up 0.38 percent per year, which is well below inflation in the US and one-month Treasury bills. It’s a horrendous return.

I don’t think that’s going to happen here in the US, but it’s a good reminder of what can happen since the Japanese stock market is the second largest in the world (available to global investors – China is the second largest if you include what’s not available to outsiders).

The second concept behind diversification is a little more technical. The basic idea is that when investments aren’t perfectly correlated, a mix can lower the overall volatility of the portfolio.

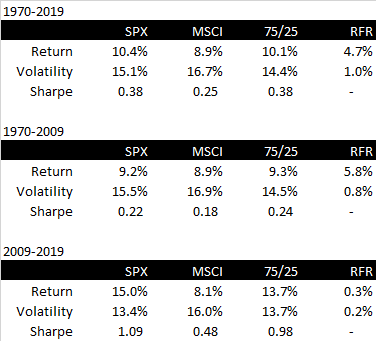

Let’s look at the data for the entire period, 1970-2019. I had the realized returns and realized volatility for the S&P 500, the MSCI EAFE, a 75/25 SPX/MSCI mix of the two and cash. You can see in the first table, that the returns for the S&P 500 are the highest, but the lowest volatility is the 75/25 mix.

This is one of the most powerful ideas in finance: the volatility of a diversified portfolio is lower than both of the constituents.

Over the entire period, you do give up some return for diversification, but the risk-adjusted return is basically the same (it’s actually higher for the 75/25 blend, but you have to go out four decimal points, so I’ll just say that they’re the same).

Okay, now let’s look at the second table, which is the information that we had at our disposal 10-years ago, before the epic rally for US stocks. This is interesting because not only is the volatility the lowest for the diversified portfolio (as expected), the return is a little better too. As a result, the risk-adjusted return is better.

The third table shows what happened over the last decade. Here, the volatility is lowest for the S&P 500 – not the diversified blend. And the risk-adjusted return for the blend isn’t as good as just the S&P 500. That’s why people are asking about whether we should bother with international stocks.

My response is twofold. First, I’ve got the diversification argument that I laid about above. I believe in both elements, the simple eggs-in-the-basket argument, and the technical argument.

But the second response, though, is to try and look less at the rearview mirror and more out of the front windshield.

If you didn’t know what the returns were for the past decade (or four and a half decades), you might ask yourself which market was cheaper. The same DFA reports that the price-to-book (PB) for foreign stocks is a lot less than for US stocks. The PB ratio looks at the price of a stock compared to its accounting value (or book value) per share.

In the US, the PB-ratio is 3.02, which means that the price is three times the accounting value. In developed international stocks, the PB is 1.61 – almost 45 percent less! There are some good reasons why the PB is higher in the US than overseas, but those arguments don’t explain that massive difference in valuation. (For emerging, the PB ratio is 1.55).

Other valuation metrics show that foreign markets are cheaper, though not always by that margin. This valuation gap has been in place for half of a decade at least, and it may not close for some time (or ever!). The point, though, is that foreign markets offer a good value, better than the US, and it makes just as much sense to look at valuation as realized returns.

Even if foreign markets were more expensive, we’d stick with them for diversification reasons, but it’s a lot easier when it’s cheap overseas. We’re not planning on increasing our weight either and intend to continue with our home country bias.