I wrote a lot about inflation in 2021 for pretty obvious reasons. I also wrote that bonds are difficult investments to own right now because the expected inflation rate over the coming decade is more than the current interest rates.

After receiving a lot of inquiries about bond alternatives like REITs, utilities, and the like, I wrote an article shooting down those too. This article is a variant on that theme: why not other, true alternatives? It’s a good question, but since alternatives can mean so many things, I’m going to tell a story about the alternative investment ‘that got away.’

Interest rates seemed impossibly low 10-years ago. I thought that they couldn’t go below zero, but guess what, they sure did! And not just for a hot minute either. But, what seemed like a low-yield environment made me investigate a lot of alternative investments.

At Acropolis, we eat our own cooking and invest alongside our clients in the same investments. As the Chief Investment Officer, I view my account as part of the test kitchen, because there is no better way to understand an investment or strategy than by owning for a few years.

I can tell you that in the test kitchen, I sometimes enjoy something sublime, but more often, I feel sick to my stomach.

With that in mind, I started investing in what I am going to call Alternative Fund X. This fund pursued a variety of arbitrage strategies. Arbitrage can mean a lot of things, but it mostly refers to when securities that should trade together for some reason, stop doing so for some reason.

Here’s one example: Back when AB InBev bought Budweiser, they offered $100 per share (I don’t remember the price, so I’m making these numbers to make the math easy). Upon the announcement, AB’s stock rose from $75 to $95, reflecting the high probability that the deal would go through.

Importantly, Bud didn’t get all the way to $100 per share until the deal closed, and the difference between the market price of $95 and $100 reflected a profit opportunity for arbitrage investors.

Most deals go through, so if they can pick up a five percent return over a few months over and over again, they can make great money, with relatively low volatility and, importantly for an alternative investment, in a way that is largely uncorrelated with stocks and bonds. Of course, this is just one strategy, it isn’t this easy and there are a bunch of complications, but you get the idea.

So, if we look at Alternative Fund X compared to the bond market since the launch of the fund in 2009, it looks pretty good:

The performance is a little better from start to finish, but there was a long, multi-year period where bonds were faring better than this fund. The volatility is pretty similar too, although the Alternative Fund X was more volatile than the bond market. And, as noted, the correlation between the Alternative Fund X is low compared to both the stock and bond market.

Based on the statistics, an optimizer would tell you to put 60 percent into bonds and 40 percent into this fund. There are a lot of reasons why you don’t follow optimizers blindly, but the point is that this fund was a good one.

Despite all that, I sold it, both for myself and the handful of clients that I bought it for. Why? Because the fund was *different* and did its own thing. Yes, that’s the informal definition of uncorrelated, but when bad things are happening, and you’re not confident in the strategy, most of the time, you don’t hang on. So, good fund, bad user.

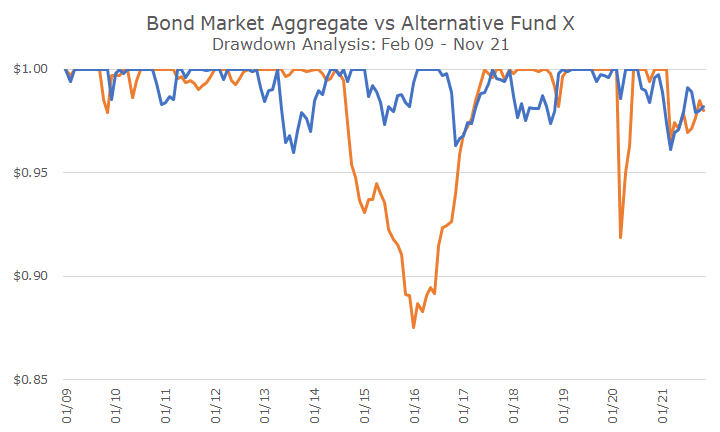

The next chart shows the rough patch that blew us out. This chart shows the drawdowns of bonds and Alternative fund X.

You can see that bonds, in blue, had periodic drawdowns, but they were never more than five percent over this time frame, and most people can handle that without much issue (especially when there are stocks in the portfolio that really grab your attention).

But the Alternative Fund X had a drawdown of more than 10 percent?

Back in the early 2010s, US companies were buying foreign companies to lower their taxes in a process known as an ‘inversion.’ A US company, paying relatively high US taxes, would buy a foreign company in a country with a lower tax rate and move the domicile to that country. If you can believe it, we almost lost Burger King so that they could move to Canada and pay lower taxes!

Well, back in 2014, Congress started rattling around and said that they were going to put a stop to inversions. There was a major deal in the works, and it was called off. If you go back to my Budweiser example, if the deal had broken, the stock would have fallen from $95 back to the pre-merger price of $75.

I understood it at the time but was so inexperienced with the strategy (it was the test kitchen!), I didn’t have the confidence to stay with it. And that was to my detriment, because not only did the strategy recover, it massively benefitted from the crazy SPAC situation over the last 18 months. That’s the spike that took it from underperforming bonds to outperforming.

It’s an old saw that the best allocation is the one that you can stick with, and a lot of what we do is help people stick with their portfolio when times get tough. It happens to all strategies and can go on for what feels like a long time. Usually, it isn’t that long, but when you’re living it day to day and can’t see around the corner, you just don’t know.

We’re sticking with stocks and bonds for the foreseeable future, in no small part because we understand them through and through, even though we can’t predict their future prices.

The last Insights for 2021 – Have a wonderful holiday and Happy New Year!