The most salient question today is whether or not the US and the rest of the world will enter a recession.

The answer, of course, is that, at some point, we will enter a recession. I think that a much harder question is when we enter a recession.

I’ve heard a few people say that we’re in one now because the first quarter’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was negative, and the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s real-time estimate for GDP is at zero. That means we may get to consecutive quarters of negative growth, which is the old definition of a recession.

Today, a recession is determined by a committee at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and they look at a variety of factors, not just the two consecutive quarters of GDP. These factors include rising unemployment, declining consumer purchases, businesses going bankrupt, people losing their homes, and post-education employment.

I’m not an expert in all of those areas, but the big one to me is the employment situation, which is still relatively good with new jobs each month and a low unemployment rate.

I’ll tackle the recession in more depth later, but today I want to jump ahead and consider the question of whether this could be like the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC).

In 2018, I saw a presentation by a local Federal Reserve official who said that there are three types of recessions. The first is when the economy gets too hot and encounters labor or capital constraints. Examples include the recessions in 1969, 1990, and 2001.

The second arises when financial conditions deteriorate, cumulatively or sharply. The 1980, 1982, and 2008 recessions are the poster children here.

The third type is when something happens out of left-field, like the 1973 OPEC oil shock. This presentation was before the pandemic, but I think we can safely add the 2020 recession to the left-field category.

If we enter a recession this year or next, I think we could make the case that it is a mix of the over-extended economy with labor shortages and the deteriorating financial conditions issue because of inflation.

I’m not ready to sort that out, but I also think it’s useful to distinguish one of the key differences between the economy today and what happened in 2008.

The 2008 financial crisis was a combination of a variety of factors, but mostly people borrowed money that they couldn’t afford to pay back, and lenders obliged (and sometimes encouraged).

The good news that I promised in the subject line is that, as of right now, the banking system looks like it’s in good shape.

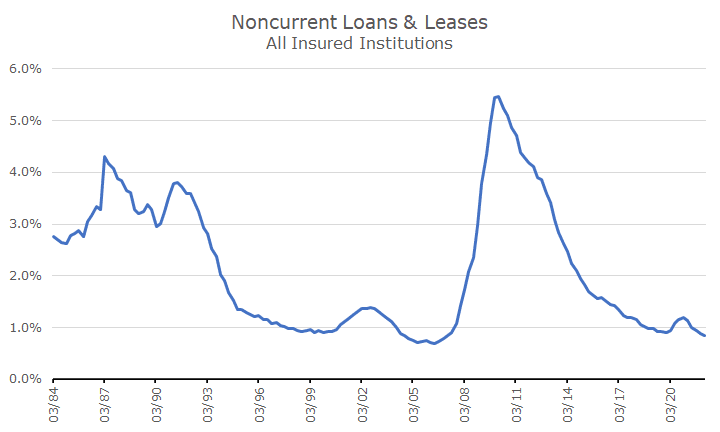

I pulled a lot of data off of the FDIC website that I found interesting, although all of it is as of the end of the first quarter. The FDIC breaks it out across the different bank sizes (community banks versus mega banks), but I just report on all banks.

The first chart shows the percentage of loans or leases that aren’t current, which is pretty self-explanatory. I find it interesting that at the worst of the crisis, 95 percent of borrowers were current, but the bigger point today is that 99 percent of borrowers are current.

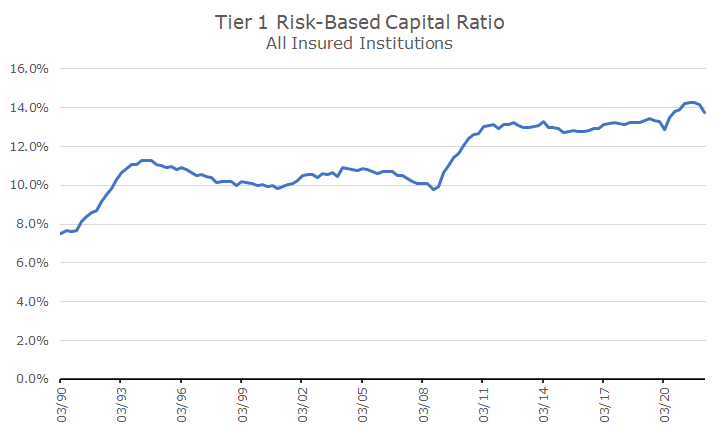

This next chart shows what is called the Tier 1 Risk-Based Capital ratio, and it’s a core measure of a bank’s financial strength.

The computations can be complicated, but the basic idea is that you want to know how much core capital a bank has compared to the credit risk that they are taking with their loans. In other words, what is the buffer a bank has compared to its loans outstanding.

The good news on this chart is that the banks have much more capital today than they did in the 2008 financial crisis. Regulators got pretty tough not wanting to have another bank run, and the capital requirements got a lot higher.

The puzzling thing to me about this chart, though, is that it doesn’t look that bad in 2008. Maybe that’s because of the government bailout, I don’t know. I know some bankers read this, so feel free to enlighten me.

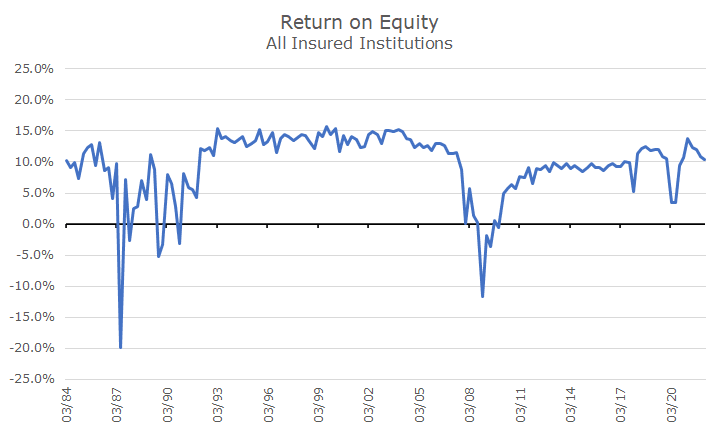

The last chart shows bank profitability, as measured by the return on equity. The Occupy Wall Street gang doesn’t want banks to make money, but the rest of us do! A bank that isn’t profitable will go under, and while the FDIC will help with most deposits, we don’t want bank failures – the knock-on effects are too powerful.

You can see that banks struggled in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which I assume is related to the slow-moving savings and loan crisis that lasted from 1986 to 1995. Then you see the 2008 financial crisis pretty starkly.

And, much to the frustration of bankers, you can see that the overall level of profitability isn’t as high after the GFC as it was before, probably because they couldn’t loan as much out in order to maintain the higher capital cushion.

So, as noted above, I think banks are still healthy. That could change, but so far, the market issues haven’t spread to the banking system.

I take heart that the crypto-collapse has been contained so far. The same with the SPACs, fintech stocks, and other frothy parts of the market that are now struggling.

That’s not to say thank bank stocks are doing fine – they’re down about as much as the S&P 500. That may not seem like great news, but bank stocks vastly underperformed the S&P 500 during the 2008 financial crisis.

As you can imagine, everyone will be looking for clues in the next round of bank earnings, but the quarter isn’t even over yet, so we won’t have any new information for another month or two.

Next week, I’ll look more at the recession question, but this week, I thought I would reflect on one of the relatively good things happening at the moment.