The mantra coming out of the 2008 financial crisis was that banks that are ‘too big to fail’ are simply too big.

Our government passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Protection Act and the countries from the G20 got together to create the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in an effort to create a safer banking system.

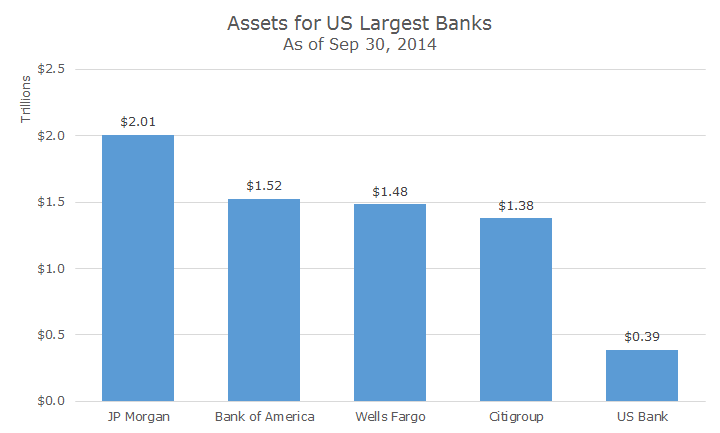

One of the great ironies of the too big to fail problem is that the banks all got bigger during the crisis as the less weak organizations absorbed the dead and dying zombie banks. The scale of the largest banks in the US is now staggering. The following chart shows the five largest banks by assets (which are effectively loans) and, yes, that’s in trillions with a ‘T.’

Last week, the FSB (the Financial Stability Board, not the new Russian KGB) proposed new rules for the 30 largest global banks that would help the banks absorb larger losses in an effort to keep taxpayers from having to bail out failing banks.

Under the current system, banks take in deposits, make loans with those funds and earn the difference between what they charge in interest on the loans and the interest they pay on the deposits, known as the net interest income.

Of course, if the loans go bad and a depositor wants their money back, a problem occurs. The FDIC (and other governing bodies) have created extensive rules to make sure that this doesn’t happen, mostly by requiring that banks hold reserves that serve as a cushion against loan losses.

As you might imagine, banks don’t want larger reserves because their profitability increases based on how much they can loan out.

Imagine a bank that takes in $100 in deposits and doesn’t pay interest (which isn’t a stretch in today’s world). If they can loan out all $100 and earn five percent in interest, their profit is five dollars. If the government requires a 10 percent capital cushion, they can loan out $90 and their profit goes down to $4.50. If the government required 50 percent capital cushion, the bank’s profits would fall to $2.50.

This is a natural and understandable tension best summed up by Charles Prince, the Chairman of Citibank going into the crisis. They were worried about the quality of loans but felt the pressure to keep making these low quality loans to keep profits high. At the time, he said, ‘as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.’

Although it will be bad for profits, I am glad to see regulators making the system safer. Analysts have suggested that the big four banks will have to raise an additional $100 billion in new capital to buffer against bad loans.

At the same time, we’re nowhere close to resolving too big to fail because the root of the system contains moral hazard. Banks earn more by taking greater risks because they believe that they will be bailed out — they keep the profits when times are good and someone else eats the losses.

There’s an old saying on Wall Street: IBGYBG. If you’re knowingly making bad loans and get a big bonus for it and someone questions whether that’s the right thing to do or not, you simply say ‘IBGYBG,’ or I’ll Be Gone, You’ll Be Gone.’ In other words, what’s the difference? We’re getting paid now to make these loans what happens tomorrow is someone else’s problem.

Even if these new rules are adopted and banks raise the additional $100 billion, who’s going to bail them out if they blow through that cushion? Taxpayers. The new rules are good and I support bank safety, but everyone should recognize that it’s a risk that’s as old as the hills and will continue on indefinitely.

As David Byrne, lead singer for the Talking Heads sings, ‘Same as it ever was.’

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott