A few years ago, I was listening to a financial podcast, and the person being interviewed said something like this: “Look, I’ve got a big China overweight in my portfolio. Look how much they’re growing – they’re going keep doing that, and I just want a part of that.”

He was clear that he hadn’t done a lot of research on China, but thought it was ‘obvious’ that they were going to grow, and it made sense to be in that market.

That forecast may still prove accurate, and while I don’t remember when I heard him exactly, so far, it’s been a rough ride.

This was supposed to be a boom time for China, as they abandoned their ultra restrictive zero-Covid policies. That hasn’t been the case, though: foreign direct investment is the worst in 30 years, their over-leveraged real estate market is struggling mightily, and Chinese investors are losing money and confidence in their market.

We’ve got some exposure to China, but not much. Our all-equity allocation has a five percent weight to emerging markets, and the index that we predominately use is 35.6 percent invested in Chinese stocks, which means that an all-equity Acropolis model has a ~1.8 percent exposure to China.

Not many of our clients are all-equity, though, so a better example might be a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio, where the China exposure is more like ~1.1 percent.

Since Chinese stocks have been faltering for a few years now, exchange-traded fund (ETF) companies are rolling out Emerging Markets exChina funds, trying to capture shifting investor preferences.

Although we’re almost certainly going to continue with our broad-market exposure, I thought I would take a look at the longer-term results between emerging market indexes that do or don’t have Chinese stocks.

I settled on the MSCI indexes, even though the index fund that we predominately use tracks a FTSE index. I couldn’t find an exChina FTSE emerging markets index. I think the FTSE would be more relevant, but I had to go with the data I have.

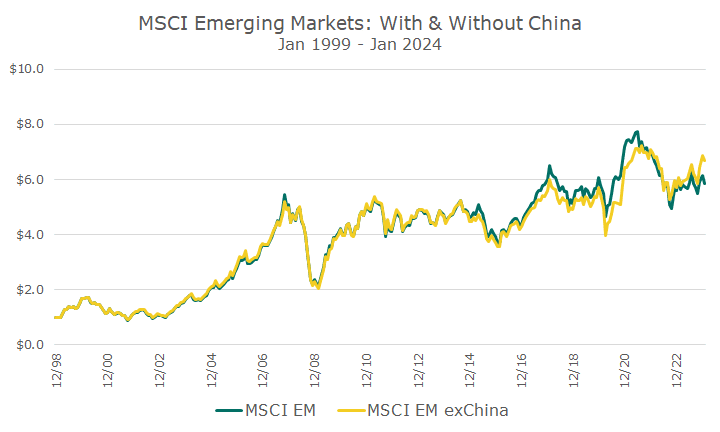

The first chart shows the MSCI Emerging Markets and the MSCI Emerging Markets exChina back to 1999.

It’s important to note, though, that there was no material exposure to Chinese stocks for the first few decades because their government didn’t allow foreigners broad access to their markets. As a result, the indexes look about the same for a long time.

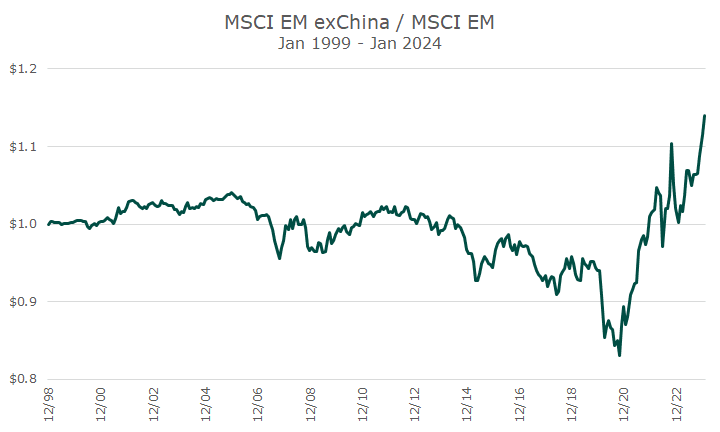

The next chart strips out the overall market performance of each of the two indexes, so you can see the relative differences more easily. It’s nothing more than dividing the exChina index growth by the overall emerging markets growth.

As noted above, there aren’t major differences until about 2013, which is probably when Chinese stocks became a more material part of the index. At first, Chinese stocks were hot, which is why the index falls in this chart (since the index with China is outperforming the index without China).

Then, at the end of 2020, when the Chinese government enforcing their zero-Covid policies, other emerging markets start to outperform Chinese stocks. At the end of 2020, the exChina index has only made about 85 cents on the dollar compared to the China index. But, barely more than three years later, it’s now earned 1.15 cents on the dollar compared to the China index.

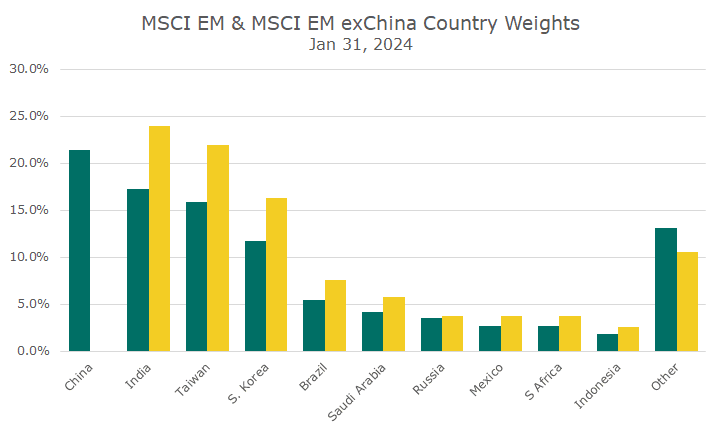

That’s pretty dramatic, but I wondered how the country weights varied between the two indexes. As of the end of last month, you can see the top ten country weights in the chart below.

China is the biggest part of the overall emerging markets index at a little more than 20 percent but is (obviously) zero percent in the exChina index. That means that in the exChina index, the weights of all of the other countries go up about 38 percent. Inda, for example, is 17.3 percent of the broad index and 23.9 percent of the exChina index, an increase of 38 percent.

I think it’s interesting that you don’t really avoid the risks associated with China by investing in an exChina index, because Taiwan is the second largest weight in the exChina index at about 22 percent.

As for whether we should adjust our exposure to eliminate China, I don’t think it’s a good idea. We’re already underweight by quite a bit. If you look at the total global equity market (MSCI ACWI), China has a 2.2 percent weight. That’s pretty small, and as I noted above, we have less than that. Shifting to an exChina fund wouldn’t really move the needle.

It’s also worth noting that there are four companies in the ACWI that have a larger market weight than all of China. I can mention two that aren’t on our Approved List: Nvidia at 2.2 percent and Amazon at 2.1 percent. The other two are household names and each one of them is twice as big as all of the Chinese stocks put together. Wow.