One of the areas of the market that we’re paying close attention to right now is corporate bonds. To raise money, companies borrow money in the form of bonds or issue stock by selling ownership in the form of equity.

Corporate bonds are safer than stocks in the aggregate because if a company fails, the bond holders get their money back before the equity holders. While corporate bonds may be safer than stocks, they are a lot riskier than Treasury bonds.

Unlike a corporation, the Treasury can print money to make the interest and principal payments. (And, the Treasury can get the Federal Reserve to buy their bonds, but that’s another story for another day).

If we compare the prices between Treasury and corporate bonds, we can get a sense of the market’s risk appetite at a given time. Sometimes, investors aren’t willing to pay very much for corporate bonds, and sometimes they’re willing to pay a lot. That variance signals investor risk tolerance, which is useful to know.

Now, the best way to look at the price of a bond is actually by looking at the yield. Here’s a chart that shows the yield on US Treasury bonds compared to Investment Grade corporate bonds since 1971.

You can see that almost all of the time, the yield is higher on corporate bonds than Treasury bonds. Investors require compensation in the form of higher yields to offset the extra risk of corporate bonds.

The trouble with the chart above is that in addition to the difference between corporate and Treasury bonds, we’re also seeing a lot of information about the level of interest rates overall.

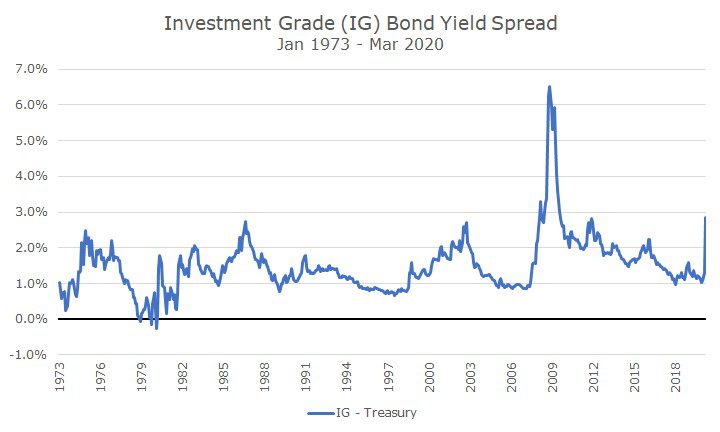

Since the level of interest rates tells a different story, let’s strip that out and just look at the difference between the two yields, what bond market investors call the ‘spread.’

The label at the bottom says ‘IG – Treasury,’ which means Investment Grade minus Treasury, referring to yield (tomorrow we’re going to look at junk bonds).

The average difference, or spread, between corporate and Treasury bonds is 1.5 percent, but you can see that there’s a range. Most of the time, that range is somewhere between 0.7 percent and 2.3 percent, but there are some extremes.

For example, you can see in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the spread is negative, which meant that Treasury bonds had a higher yield than corporate bonds. I’m not sure why that happened, but my first guess is that the level of interest rates was just so high, that people wouldn’t pay up.

We see the opposite in 2008, when the spread jumped to 6.5 percent. At that point, during the 2008 financial crisis, investors were worried that corporate bonds would miss their interest payments and default on their bonds, so they demanded huge yields to offset that risk.

In the bond market, we call that ‘blowing out,’ although I’ve always thought we should just say blowing up.

As the economy got back to normal after that recession, the spread on corporate bonds fell back to normal levels and then the spread became narrow, what we call ‘tight.’

And, finally, in the last two months, you can see the spread blow out again, as investors sold off corporate bonds and bought the heck out of Treasury bonds.

We can see that at almost three percent, the spread is the widest that it’s been outside of the 2008 financial crisis. But, still, at three percent, it’s less than half the level it was in 2008.

When spreads blow out, corporate bonds are suddenly more attractive, but they’re scarier because of the higher risk. Does that sound like stock market investing? It should, especially since corporate bonds and stocks are appendages of the same animal.

Because the spread between Treasury bonds and investment-grade corporate bonds was narrow, we decided to reduce our exposure to corporate bonds to underweight the market at the end of 2018. The next year, that didn’t look like a good idea because spreads began tightened further. But, it’s looked so good this year, that it made up for all of last year.

At this point, we haven’t made any decisions, but it may make sense to consider over-weighting corporate bonds again. Obviously, corporate bonds entail more risk but with the Federal Reserve backstopping the market to some extent, corporate bonds may make sense.

Time will tell – we need to do more research and consider the risks and potential benefits. But, given the size of our bond allocation, I thought it might be interesting to show you the kind of thing that we’re evaluating as we shelter-in-place.