Last week, I was asked to consider writing an article about how the dollar’s strength or weakness impacts a portfolio.

I’ve covered it a bit over the years, but I thought now would be a good time for an update, and I’m always interested in writing about what readers want to read about, so I try to address specific issues whenever possible.

I will illustrate later how the dollar has impacted developed and emerging markets stocks, but the dollar goes beyond those foreign stocks.

For example, when a US company manufactures a product in Mexico and sells it in Europe, the exchange rate between the dollar and peso matters as well as the price of the dollar compared to the euro. Therefore, what happens to the dollar matters greatly to US companies that do business overseas, which is almost all large-cap companies.

That’s also what makes “the dollar” a little hard to measure because it has an exchange rate with every country in the world with a currency. The dollar can be strong against the Japanese yen but weak against the Swedish krone.

Since I like to illustrate concepts in charts, I thought I would show the difference in returns in the developed and emerging markets over time. I used data from MSCI and went back as far as I could.

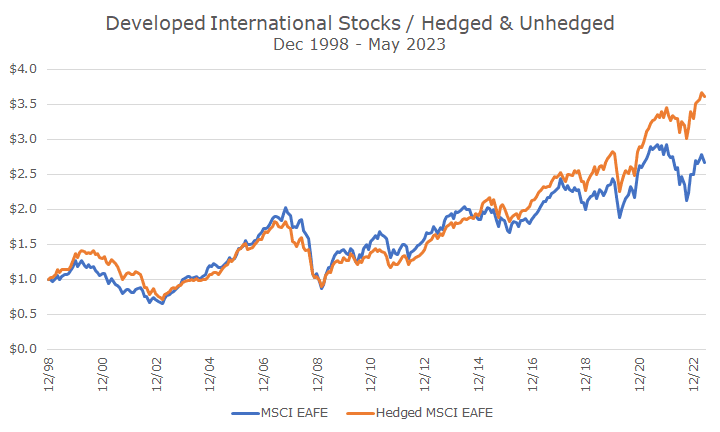

The first chart shows what a US investor would have earned in the major index of developed market stocks on a hedged (in blue) and unhedged (in orange) basis.

In the unhedged version, investors are taking currency risk. If you buy Nestle, for example, you’re taking the risk of whatever the Swiss franc does versus the dollar in addition to the risk of Nestle stock (forgetting that Nestle buys and sells all over the world and the risks associated with that, as outlined above.

In the hedged version, an investor buys the equivalent of Nestle but engages in an additional transaction to remove the currency risk.

The chart shows that the returns were roughly similar for a very long time until the pandemic, whether you hedged your currency risk or not.

During the pandemic, the dollar was very strong, which was bad for investors who didn’t hedge the currency risk — US investors who hedged the currency risk benefited by not having exposure to other currencies.

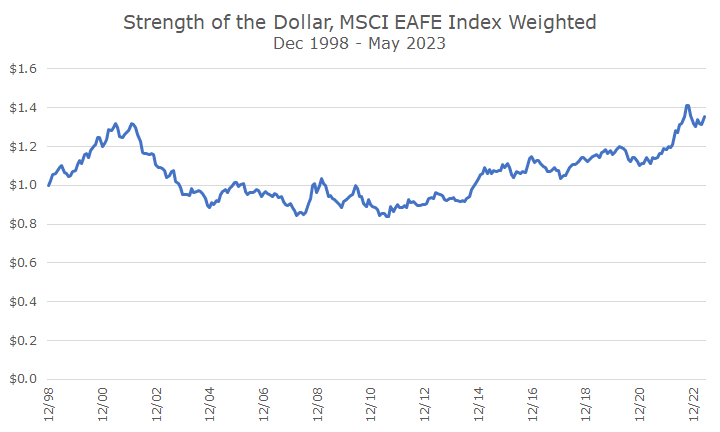

The chart below shows how the dollar impacted returns over time. You can see that in the late 1990s (when I worked in foreign exchange), the dollar was very strong, but then gave up all of the strength in the early 2000s recession.

The dollar was essentially flat until 2014 and then gradually strengthened until it took off at the pandemic’s start. Then, you can see it sold off some recently.

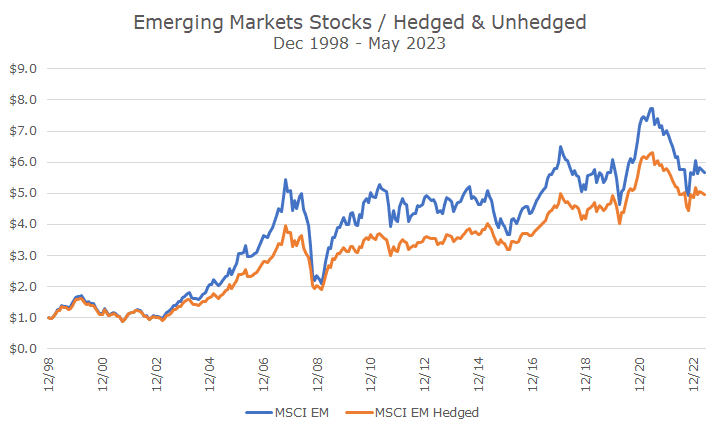

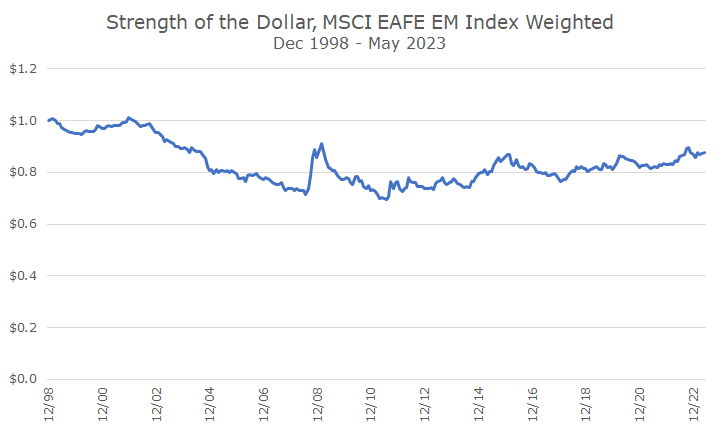

The following two charts show the exact same thing over the same period, but now look at emerging markets instead of developed ones.

In emerging markets, the impact is quite different. While the dollar was strong against the euro, yen, and other developed market currencies, it wasn’t against the Chinese yuan, Taiwanese dollar, and Indian rupee (the largest three currency exposures constituting about 55 percent of the index).

It’s surprising that the dollar would have fared better against developed markets than emerging ones. That’s part of why we don’t attempt to pick and choose what we should hedge and leave unhedged.

Investing overseas has typically carried currency risk. Five or ten years ago, many products hit the market that took the same country and market risks but hedged out the currency risk.

Our view is that, on average, over the long run (which sometimes feels like an eternity), the currency impact should be minimal because the long-run expected return on a currency is zero.

The hedged products cost about seven times more than the products that we use, and we would rather not pay up for an exposure that we don’t think adds a benefit in the long run.

It would have paid off in the last five years, but that could reverse in the next five years as it did in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The price of the dollar is another important and impactful thing that is also impossible to forecast with any accuracy, like stock prices, short- and long-term interest rates, inflation, elections, and the next TikTok craze. Okay, that one isn’t important or impactful, but it is baffling.