James Grant is one of my favorite market gadflies. He is the editor of the eponymous James Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, a columnist for Barron’s, and host of the Grant’s Current Yield podcast.

Grant is intelligent, funny, and a long-term market skeptic. I’ve heard him say he doesn’t like being described as a perma-bear, but he’s been bearish for as long as I can remember and seems a true gold bug.

So, I don’t follow his investment recommendations, but I always like to hear what he has to say because he’s insightful and engaging.

In a recent episode, he read a quote from Scott McNealy, the billionaire businessman who co-founded Sun Microsystems, a darling of the late 1990s tech bubble that crashed in the tech wreck.

In 1998, the stock traded at $100 per share, rose to as high as $250, and then fell to less than $10 (but recovered to $20 before being bought by Oracle).

According to Grant, McNealy said of the stock’s collapse:

We were selling at 10x revenues. At 10x revenues, to give you a 10x payback, I have to pay you 100 percent of revenues for ten straight years in dividends. That assumes I have zero cost-of-good-sold, which is very hard for a computer company. That assumes zero expenses, which is really hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that assumes with zero R&D over the next ten years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate. Do you realize how ridiculous those basic assumptions are? You don’t need any transparency. You don’t need any footnotes. What were you thinking?

He’s scolding the market for taking the valuation too high, at 10x sales.

And he’s right.

Think about it. If a company has revenues of $1 million, at 10x sales, the market value is $10 million. He’s saying that the entire $1 million has to be profits, which is impossible, and that even at that level, it would take ten years to get your money back with no interest.

Of course, he’s oversimplifying for effect. The company shouldn’t be worth zero in ten years, and the point of that valuation is that the market expects growth: lots and lots of growth.

What’s relevant about McNealy’s quote today? Nvidia, which makes processors that power artificial intelligence (and appears to be missing a vowel), is now trading for 41x revenue.

That’s right—41x revenue. The 10x revenue that McNealy is talking about seems almost pedestrian compared to Nvidia.

In the most recent 12 months, Nvidia has had revenues of almost $26 billion, which is impressive given that their revenues were $11 billion in 2020. The market value of Nvidia’s stock is 1.05 trillion. That little $0.05 over $1 trillion – that’s $50 billion, or twice the company revenue.

While Nvidia is in a class by itself, I counted about 35 companies in the S&P 500 with market values of more than 10x revenues. Wow. And they’re not all associated with artificial intelligence, the hot topic de jour. One is MSCI, the index provider, which trades at almost 17x revenue.

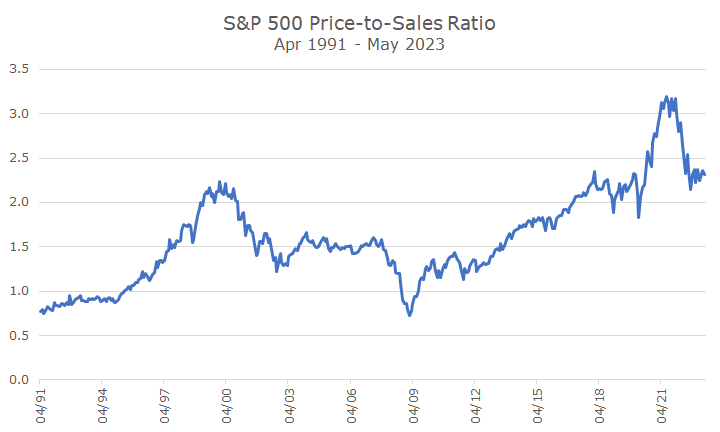

Naturally, I wondered about the overall market and found that it traded 2.3x price-to-sales as of May. That seemed expensive to me, so when I pulled the historical data from Bloomberg, I could see why – that’s about the level in the tech bubble, which cooled off to 1.5x in the aftermath.

I’m not calling for a 2001-style tech wreck. Long-time readers, and maybe even short-time readers (is that a phrase?), know I don’t call for drastic action.

I want to maintain our buy-and-hold approach when stocks are cheap like they were on this basis in the 2008 global financial crisis (and rebalancing, to buy a little more stock). And, I like to buy-and-hold when they are expensive, like a year or two ago (and rebalance again, and sell a little stock).

That said, I’m happy that we don’t own any Nvidia stock, which is odd because it’s up 192 percent so far this year. I don’t mind missing that kind of performance, because I don’t think it will last. I could be wrong; it may be the best stock of the coming decade.

I fear that it’s like the Ark Innovation fund that rose 250 percent from March 2020 to March 2021, only to less all those gains by March 2022. A lot of money was lost because most investors poured in after the big gains and held on through the big losses.

But Nvidia could be like Tesla, which seemed like it was on the verge of bankruptcy right before it shot up 1,500 percent. Tesla is down recently but is still up 1,000 percent in the last five years.

These examples are why we don’t bet big on any company. And why we hold an index fund that owns just the S&P 500. All of these momentous gains and losses are happening inside the index.

We caught every bit of the Nvidia gain in the index, and it’s now the fourth largest holding in the S&P 500 at 2.7 percent. If it continues to rocket forward, we’ll catch part of that, and if it craters, we’ll catch that too.

That’s the power and the beauty of diversification and indexing. I wouldn’t have the nerve to buy Nivida on its own. But when it’s paired up with another 499 stocks or several thousand if you consider our other equity asset classes, I can live with it.