In last week’s market turbulence when the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) fell by 1,100 points in a single day, I had to talk about something that I don’t like talking about: the DJIA itself.

For the most part, I’m able to avoid talking about the DJIA, which is nice, because I think the index is pretty much an almost worthless relic of history.

That said, when markets are volatile and people ask me what’s happening, I know that they want the answer in DJIA points and in the form of a percentage change for the lesser known but far better index, the S&P 500.

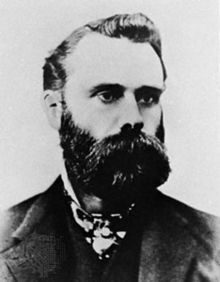

Back in 1896 when Charles Dow (pictured with an admirable beard) first created the DJIA for his financial news bureau, Dow, Jones & Co., it was a real innovation.

Dow Jones had 1,000 subscribers that followed the market and a series of mergers in 1893 created a number of large corporations and Dow wanted an easy way to track the performance of all of them.

He picked 12 companies (including St. Louis utility Laclede Gas), took their prices and divided by 12 (hence the word ‘average’ in the name).

It made sense at the time and when Dow and his partners launched the Wall Street Journal in 1889, it included the DJIA.

In the ensuing 119 years, however, there have been some useful innovations that improved on the DJIA. The most important enhancement was to weight the indexes by the size of the company, not the price of the stock, which is pretty random.

The largest stock in the DJIA today is Goldman Sachs with a 7.5 percent weight and the second smallest stock is Verizon (the smallest is on our Approved List, which prohibits me from talking about it for regulatory reasons) with a 1.8 percent weight.

Why is the weight in Goldman four times larger than Verizon’s? It’s not because they are bigger: Goldman has a market capitalization of $81.6 billion, which is pretty good, unless they’re being compared to Verizon, which has a market cap of $187.1 billion – more than double Goldman’s market value.

The reason that Goldman has a bigger weight is that its stock price is around $188 per share, while Verizon’s is only $45 per share – a difference of fourfold. Charles Dow should have cared that Goldman only has 451 million shares outstanding compared to 4.1 billion for Verizon.

The other quirk for the DJIA is that a committee picks the constituent stocks and they have famously picked stocks after large run ups that suffered after being added.

The Dow committee added two of the most famous tech stocks in 1999 (again, they’re on our Approved List) and Bank of America at the outset of the 2008 financial crisis (it lost 90 percent in the year after it was added).

One stock (that I can’t mention by name) was added to the index in 1932 only to be removed in 1939 and re-added in 1979. If that one stock had stayed in the index, it’s been estimated by research firm Global Financial Data that the DJIA would be 22,000 points higher than it is today.

That leads to the third problem for the DJIA: it’s very concentrated with just 30 holdings and, therefore, isn’t representative of the overall market. Even the S&P 500 suffers from this to some degree since it represents 70 percent of the total market, but that’s still a lot better than the DJIA.

Despite my misgivings, I also know that when the DJIA moves in an out of the ordinary kind of way that I will have to report on it. But now I can link to an article that describes its folly when that time comes.