Each month, Bloomberg asks 75 professional economists to forecast a variety of economic indicators. At this time last year, the median forecast among the economists for inflation-adjusted (or real) economic growth was 2.6 percent.

At this point, we don’t have enough data to say what actually happened, but it looks as though the estimates won’t be too far off base. Assuming that the fourth quarter numbers come in as expected at 2.5 percent, real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) looks like it will come in at 2.5 percent.

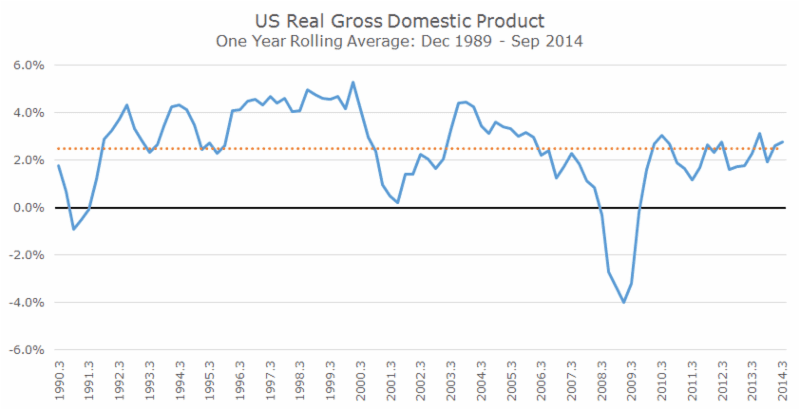

To put that into perspective, I pulled 25 years’ worth of quarterly data and found the average growth for every one-year period in the data. I was surprised to find that the average growth rate was 2.6 percent, a fair amount less than the three percent that I was expecting and not too far above the current growth rate.

Looking at the above chart, three things stand out in my eyes. First, you can really see the recessions – first in 1990, then 2001 and finally in 2008. That leads me to my second point, that the 2008 financial crisis was really horrible – much worse than the previous two recessions.

Finally, if you simply look at how the blue line, which represents the rolling one-year economic growth rate, compared to the dotted orange line that represents the average for the whole period, you can see that the first half of the period was a lot better than the second half.

I’m not doing any hard core analysis here; I am simply saying that growth between three and four percent really hasn’t happened since coming out of the recession in the early 2000s and that was fairly brief. You have to look at the 1990s to see any sustained growth over three percent.

Although it’s presented in many different ways, the persistent slow growth that we see in this chart is often referred to as ‘the new normal’ by clever marketing folks and ‘secular stagnation’ by actual economists.

One of the most important questions coming out of the financial crisis was whether or not the slow growth that we are experiencing is a temporary phenomenon or a permanent condition. Of course, in this case ‘temporary’ is measured in years and ‘permanent’ isn’t really forever, but measured in decades.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any unusually good insight into how long this low growth rate will last. It does seem reasonable to me that we should expect low growth for the next decade, partly because people are still cautious after the 2008 financial crisis and partly for two structural reasons: slower population growth and less productivity growth.

In the near term, though, it seems likely that we’ll continue to slog out some slow, bumpy growth. I realize that’s a pretty murky forecast, but no one else can offer anything more credible.

The median forecast for 2015 by the economists that Bloomberg surveys show a growth rate of three percent when you look at the annual number. When you break them down by quarter, though, not a single quarter comes in over 2.8 percent. How does that work?

My favorite forecasting group, Vanguard, thinks that there’s a 43 percent chance that growth will be between 1.5 and 3.5 percent, a 33 percent chance it will be below that range and a 24 percent chance it will be above that range. They’re my favorite not because of their accuracy, but because I think they are fair and largely unbiased. On the other hand, their forecast is so broad, they’re not saying much more than I am.

Perhaps you trust the Federal Reserve. The central tendency for their individual estimates is 2.5 to 3.0 percent. Last year, they thought that real GDP growth would be 2.8 to 3.2 percent. They could still be right, but it’s useful to remember that they have good reason to put out rosy numbers.

So, that’s a long way to say that no one knows that the economy will do in 2015, but most people, including me, think that it isn’t likely to be a terrible year, but won’t be a great year either. It will likely be another year of sluggish growth, but we could all be surprised to the down or upside.