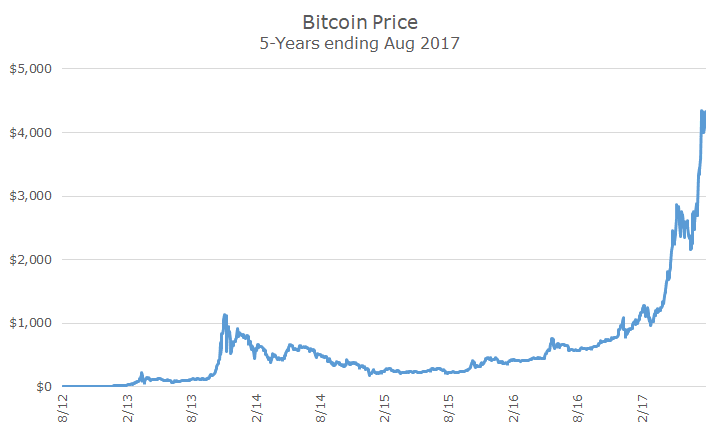

In 2013, when Bitcoin prices were surging, a few readers asked me to write about Bitcoin. I didn’t know much about it and didn’t write the article because I thought that Bitcoins didn’t seem legitimate, but they’re on a tear, so I’m giving it a shot.

Bitcoin is the first, largest and best-known crypto-currency. But what is a crypto-currency? That’s a harder question. To answer it for myself, I thought about the definition of money, which traditionally has three components.

First, money is a medium of exchange, which simply means that, as a society, we use money s an intermediary that is used to avoid the inconveniences of bartering. The local grocery store won’t accept my cowry shells in exchange for food (or half of a cowry shell for half as much food).

Second, money is a unit of account, which means that it serves as a standard, numerical measurement of market value for goods and services. Money has to be divisible into smaller units without losing value, which is why we can use gold as money but not a Picasso.

Who would accept half a Picasso as payment? As a unit of account, money has to be fungible where one unit is equal to another. That’s true for $100 bills, but not diamonds, which vary in carat, color, and clarity.

Finally, money is a store of value, which means that I can save it for later and use it as a medium of exchange in the future. Obviously, saved money has to maintain its value to be useful in the future.

When Germans tried to spend their Weimar Republic reichsmarks in 1933, they weren’t worth the paper that they were printed on, which meant that the old currency was used as wallpaper and in the furnace for heat.

If you think about the money in your wallet, it fits those definitions. So does the yen in a Japanese person’s wallet or euros in the Frenchman’s billfold.

Gold meets those standards as well with an important additional feature: it’s not tied to a particular government. The gold that I own can be used in Japan, France and anywhere else in the world. That was true thousands of years ago and will almost certainly be true in the future whether you think it makes sense or not.

Getting back to crypto-currencies, let’s look at how they meet our three tests. Are Bitcoins a medium of exchange? Yes, they have a universal price and can be used in exchange for goods and services instead of traditional currencies. Are Bitcoins a unit of account? Yes, one Bitcoin is one Bitcoin, anywhere in the world.

Are Bitcoins a store of value? Hmm… Yes, so far they have been a store of value. In fact, as noted at the top, they’ve been a phenomenal store of value – you can buy far more goods and services with a Bitcoin today that you could at any time in the past. That said, I am personally skeptical that they will be a good store of value in the future.

I may be completely wrong about that, as I have been so far. And, I don’t have any particular evidence to back up my claim except that crypto-currencies are new.

I trust my US dollars because even though they are new compared to gold, they’ve worked my whole life. Maybe if I had been born in Zimbabwe, which experienced hyperinflation that made their currency worthless, I’d have a different view.

In addition to the newness, my other problem with Bitcoin is that it is somewhat tainted by scandal and theft. The Silk Road marketplace, which helped put Bitcoin on the map, was a large platform for selling illegal drugs.

The anonymous nature and the ability to use Bitcoin electronically created an easy way for criminals to do business. It’s true that regular currencies were used in illegal transactions long before crypto-currencies, but Bitcoins make it easier to evade detection. Anonymity in the real world requires large amounts of physical cash or gold, which creates problems that make it harder for criminals.

In addition to being the currency of choice for criminals, crypto-currencies have been lost or stolen. In 2014, the largest Bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, announced that 850,000 Bitcoins were ‘missing.’ At that time, those Bitcoins were worth $450 million and represented about six percent of all Bitcoins at that time.

Since then, about 200,000 of those Bitcoins have been ‘found,’ but the size and mystery of the loss is enough to keep me away.

Lastly, I’ve got some small operational concerns. I view gold as a doomsday currency, but I don’t think Bitcoins would work. If there’s an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) that wipes out computers, the money that I’ve got in bank and brokerage accounts won’t be very useful. If I had gold, maybe I’d be okay, but Bitcoins won’t help me in that particular scenario.

It hardly seems like the end of the world for Bitcoin owners – just the opposite, in fact. They are riding high; so much so that it feels like a bubble to me.

Maybe my grandkids will lament the fact that I could have bought a Bitcoin for just $4,344 and didn’t, but hopefully, they’ll be satisfied with the stocks that I bought them instead. Either way, I think that crypto-currencies are here to stay.