Given the low interest rate environment that we’ve endured over the last several years, a lot of our clients ask how we can increase the yield of our portfolios.

While yield is an important component of total return (which is income and appreciation/deprecation together), we sometimes see investors stretch for yield without fully understanding the consequences of their decisions.

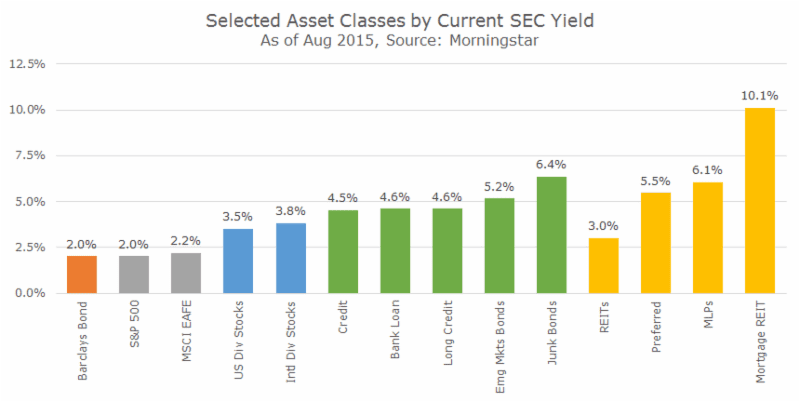

The table below shows the SEC-yield (which is a whole story unto itself for another day), for 14 different kinds of assets. The lowest yield, in orange, is for the Barclay’s Aggregate Bond index.

Right next to it in grey is the S&P 500 and the MSCI EAFE index of international stocks. Although we can do a little better and this is oversimplified, those yields are a good approximation for our portfolios.

Next, in blue, are two S&P indexes that tilt stock portfolios towards dividend stocks. The yields are, on average, about 1.55 percent higher than the non-dividend tilted indexes.

The next five bars are various high yielding bond strategies. The only one that we invest in for our clients is credit, which is another, more technically accurate name for corporate bonds. The four have higher yields culminating in junk bonds, which are head and shoulders above the other four (for more on why we avoid junk bonds, click here)

Finally, in yellow, I’ve included five strategies that are often considered good sources of yield. We invest in REITs (or Real Estate Investment Trusts), although the yield isn’t much better than traditional stocks and bonds.

Preferred stocks are hybrids of stocks and bonds, MLPs are master limited partnerships (more details here) and the last are mortgage-REITs, a subcategory of REITs that we avoid like the plague for reasons that you’ll see in a minute.

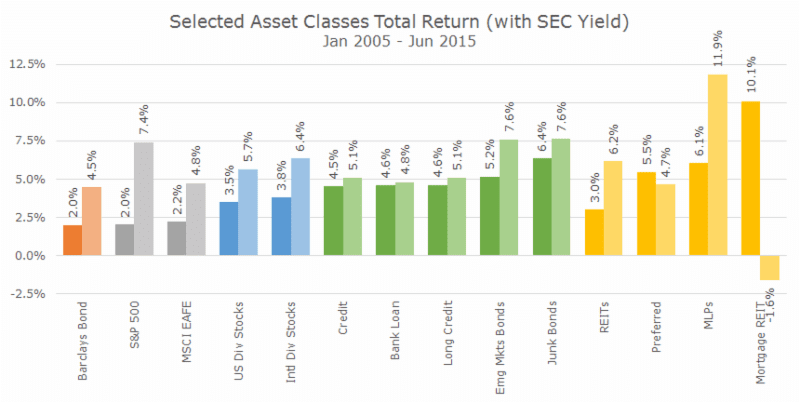

The first thing that I think people need to realize is that yields and returns aren’t the same – yields are only part of the equation. I adapted the chart from above to include the total return for the last 10.5 years (that was as far back as the mortgage-REIT index went).

Notice how the yields and the returns (over this period) are often quite different. First, take a look at how the dividend-tilted portfolios fared (vs. the grey bars) – where this approach cost you in the US and helped overseas.

The most dramatic differences are in the alternative yield section. MLPs had returns over the past 10.5 years that were nearly 12 percent – much better than the current yield. However, mortgage-REITs actually lost money despite the big income.

This isn’t a perfect analysis (comparing past returns to current yields), but hopefully it breaks the idea that yield equals return.

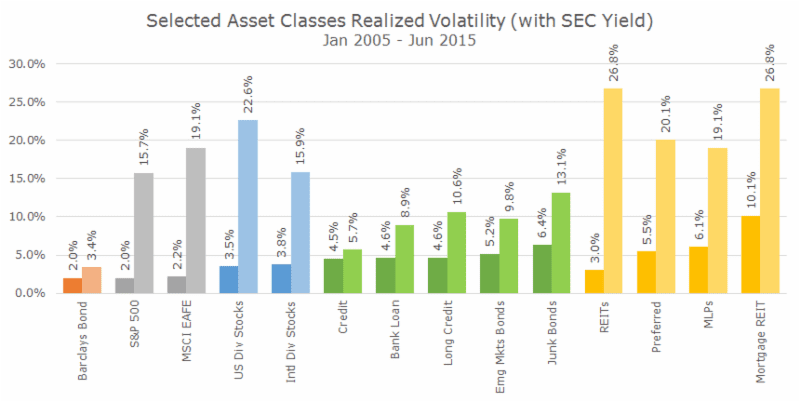

Of course, investors don’t care just about returns, they also care about risk. In the following chart, I show the same indexes, still with their current yield, but with the realized volatility of each index over the same time period.

When you look at the bond alternatives, in green, you can see that the volatilities are much higher than the volatility for the good ol’ fashioned Barclays Aggregate. The volatility for junk bonds is almost four times higher. It’s not as much as stocks, but it’s about 85 percent of the way there. That’s partly because of the financial crisis, but the point is that there are risks in those higher yields.

It really gets nutty when you look at the volatility on the alternative yields, where realized volatility was the same or much higher than stocks. Again, this is partly due to the 2008 crash that was particularly tough on REITs and mortgage-REITS, but when people tell me that they are investing in any of these asset classes as bond alternatives, I shiver.

All this isn’t to say that these asset classes are bad – after all, we use some of them like corporate bonds (credit) and REITs.

I’m simply saying just because something has a high yield, it isn’t necessarily a good investment and, when you do see higher yields or higher total returns, you have to know that risk and return go hand in hand, there just simply isn’t a free lunch.

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott

- David Ott