The junk bond market was under pressure again yesterday, but managed to finish off of their worst levels. The high yield market was roiled again after one hedge fund, Lucidus Capital, announced that it was shutting down its $900 million credit fund, and another hedge fund, Stone Lion, said that they were suspending redemption on their $400 million fund.

This comes after news from last week that Third Avenue, a well-known value/distressed investment firm, announced that they would stop honoring redemption requests and would liquidate their funds.

Since then, Third Avenue announced that their CEO David Barse, who has led the firm since 1995, was stepping down and that Massachusetts securities regulators will be investigating the details surrounding the abrupt closure.

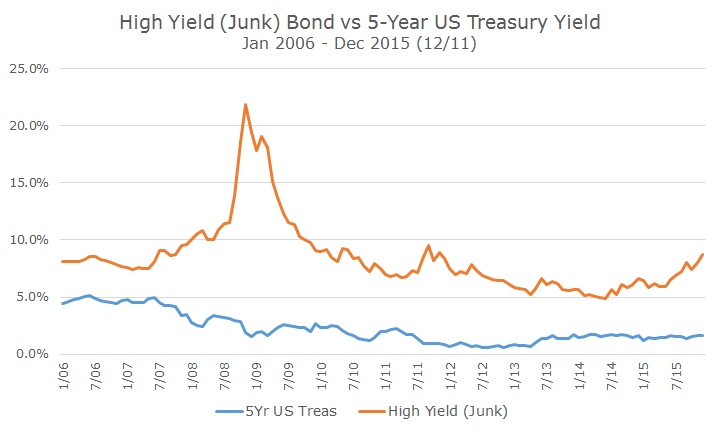

Like a picture, I think a chart is worth a thousand words. The following chart shows the yield for the Barclays High Yield (junk) index compared to the yield on the five-year US Treasury note.

It’s not a perfect comparison because the durations don’t match exactly, but it’s close enough to get the idea; the duration on the Treasury is 4.79 years and is 4.39 years on the High Yield Index.

The blue line shows the yield on the five-year Treasury and you can see that over the last 10-years, it has fallen from around five percent to 1.65 percent today after hitting a low of 0.60 percent. Remember, when yields fall, prices rise and when yields rise, prices fall.

The orange line is the yield on the Barclays High Yield bond index, which starts around 7.5 percent, jumps to over 20 percent in the crisis and then falls down to five percent last year.

The interesting part is that you can see the yield climbing, which means that prices are falling, especially compared to the Treasury yield, since June 2014. The rout in junk bonds is not new, it’s just intensified in the last week.

Even after last week, we’re nowhere close to where we were at the peak of the crisis, but a lot of people are wondering whether what we are seeing today is a prelude to a crisis, just like back in 2007 and early 2008. I’ve thought it too, because I vividly remember when two Bear Sterns hedge funds abruptly closed down and less than a year later Bear was gone.

I’m not convinced that junk bonds are the canary in the coal mine. It’s possible, but I also think that this kind of analysis leads to a lot of false positives. After all, if it was a lock, we would already know one way or the other.

Although I am not a chart reader, you can see in the chart above that when junk bond yields were rising in 2007 and 2008 that Treasury yields were declining – the spread between the yields on the two assets was happening at both ends, whereas today it’s confined to the junk market.

If Treasury yields were falling too, I would think that the problem goes far beyond the junk bond market.

You can’t see this in the chart, but the overall financial system is a lot less leveraged than it was leading into the 2008 financial crisis (now the government holds a lot of the debt that was in the financial sector).

Banks have more capital and investment banks are completely different animals than they were 10 years ago. Also, all of the bad loans back then were based on the idea that home prices couldn’t go down – models by the ratings agencies assumed that loans backed by real estate were AAA.

In this case, everyone knows that junk bonds are junk – hence the name. It’s true that some investors get caught up holding too much illiquid paper and find themselves in a death spiral like Third Avenue’s credit funds, but that’s not going to happen at the highest levels like it did in 2008.

Still, the junk market bears watching because even though we don’t have direct exposure to junk bonds, markets are highly inter-related. If a large fund or institution has too much exposure to a sector that’s getting crushed, they may have to sell their liquid assets at any price, which can push around liquid markets.

We’ve had our eye on junk for a while, not to buy it or because we own it, but because it impacts what we do own and may buy.