Several years ago, I was convinced that bond yields were likely to move higher simply because they were at historic lows. As time went on and bond yields fell to even more historic lows, I changed my tune.

People asked me how much lower they could go and while I didn’t really know the answer, I would simply quote the yields in Germany and Japan, which were lower.

Then, I started to say that they could go to zero, really not believing that they could go below zero. I had seen zero rates on Treasury bills during the 2008 financial crisis for a day or so, but that seemed different.

An article in Bloomberg a week or so ago got me thinking about this again because they were talking about how the yield on the 10-year Japanese government was negative and how long the yield on the 10-year there has been below two percent.

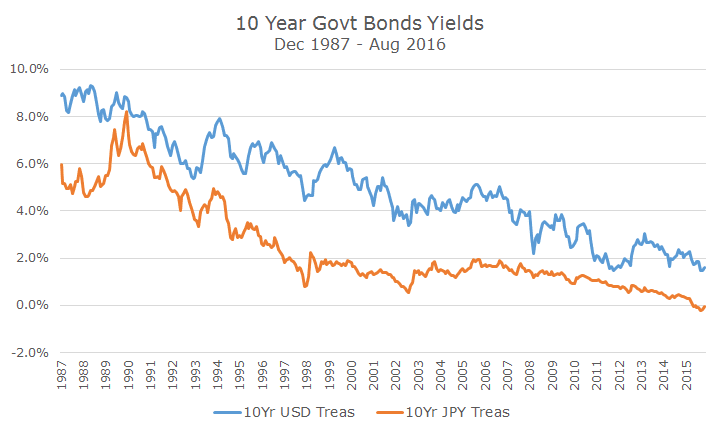

You can see in the chart above that the 10-year yield in Japan (in orange) first fell below two percent in the late 1990s and has been almost permanently below that level since then.

There is nothing special about two percent per say, but the thrust of the article (which I tried to find over the weekend and couldn’t), was that the 10-year yield has been below two percent for almost 20 years.

Our own 10-year Treasury fell below two percent in 2011, but then went reasonably back above that level until this year when it fell back down again.

In my mind, the question has changed from how far will rates fall to how long will they stay so depressed? Just as I looked to Japan a few years ago, I think it makes sense to use them as a reference again.

That’s not to say that our issues are just like Japan or that we are destined to have a Japanese like experience, but simply to say that I think that bond yields could stay down at this level for a long, long time.

The chart below shows the yield history for the US and Japan since crossing below the two percent level. I wish that I had labeled the x-axis to show the number of years, but the idea is that if we do end up with a Japanese like experience, then we’ve only just begun.

Not only have Japanese investors been dealing with low rates for 15 or so more years than we have, they are farther from two percent than ever and there are no obvious signs that they are getting back to two percent anytime soon.

I could be proven wrong any day, but it seems to me that the risk of sharply higher interest rates in the US (or Japan) isn’t particularly high today.

Of course, that can change quickly in unforeseen ways, but the risks of sharply higher rates don’t seem high in the near term and the Japanese experience suggest that the risk may not be high for the long term.

It sounds funny, but I wish the risk of higher interest rates was higher, even though it would hurt our bond portfolios in the short run. But the reason that rates are low is that markets don’t see much economic growth – just as they didn’t for Japan 20 years ago.

I would prefer that markets thought that robust growth was around the corner, which should support earnings and stock prices. For now, though, and in the foreseeable future, it appears that low economic growth is on the horizon.

The silver lining is that inflation should also be subdued, as it has been in Japan. Indeed, they’ve struggled with deflation and were thrilled to get inflation over two percent in 2014 (although its CPI was only 0.19 percent in 2015).

As always, we will do the best that we can in the environment that we’re dealt. Although it wasn’t based on the Japanese experience, we did extend our duration a few years back from around three or four years to five or six years.

So far this decision has helped and if rates fall or stay roughly the same for the next 15 years, it will have proven to be a good call. If rates spike unexpectedly, we’ll wish we were short term again, although a bear market in bonds is not nearly as dramatic as a bear market in stocks.

One of the popular phrases on Wall Street for the last several years has been ‘lower for longer,’ referring to short term rates set by the Fed. I would say that even though we are likely to see some kind of Fed action in the coming months, the ‘lower for longer’ mantra still holds across the curve.