When I graduated from college and started working for Mark Twain Bank’s brokerage unit, there was an older gentleman who occupied one of the offices in the branch. I’m not sure he was actually employed by the bank at that point, but I was told that he had been an important executive at one time.

He came in around nine, read the newspaper (we all did in those days), made a few phone calls, probably scheduled a tennis game and left around noon for a lunch appointment.

This fine old fellow didn’t have a Quotron, the old-fashioned machine that told us what was happening (pictured below from the movie Wall Street), and so he would pop into other brokers’ offices to see what was happening with the market.

I thought of the old elephant’s graveyard when I read about a mutual fund that caught my eye last week. This fund, the GAMCO Mathers fund, has the strangest performance that I have ever seen.

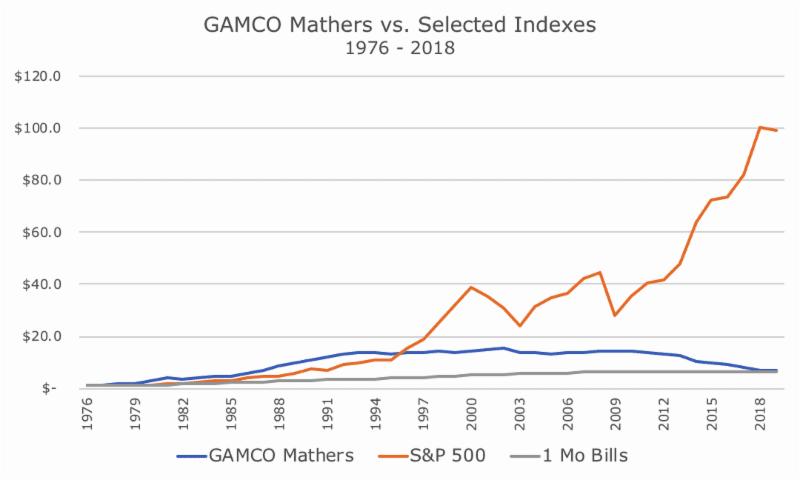

Taking data from the company’s website, which you can find here, I charted the annual results since 1975. The fund was in existence since the mid-1960s, but the fact sheet doesn’t break out the performance annually until 1975.

The fund lists its benchmark as the S&P 500, so I’ve included that along with one-month Treasury bills, which are a proxy for cash. You can see that since 1975, the fund basically earned by cash returns, but the chart above doesn’t really tell the full story.

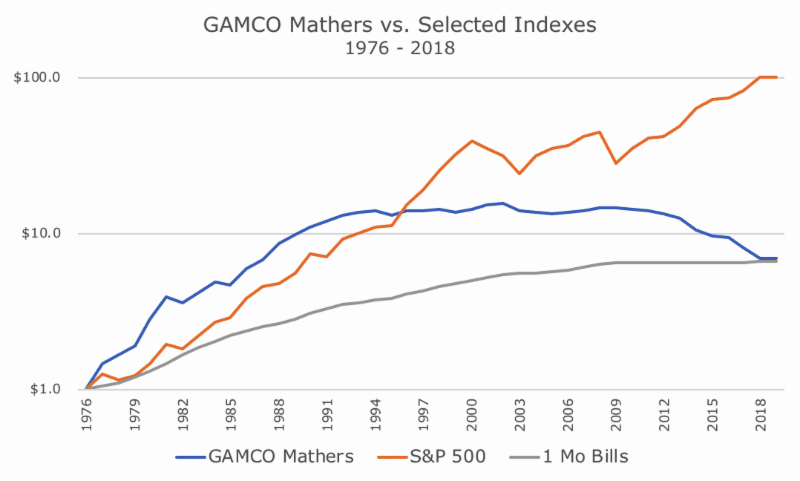

The chart below shows the same data, but lays it out logarithmically so that you can see the early years in better context.

Viewed this way, you can see that the fund dramatically outperformed the market in the early years, leveled off for a while and then suffered some losses in recent years. But even looked at this way, you can’t really see how bad the returns have been in recent years, so I’ve included a drawdown chart too.

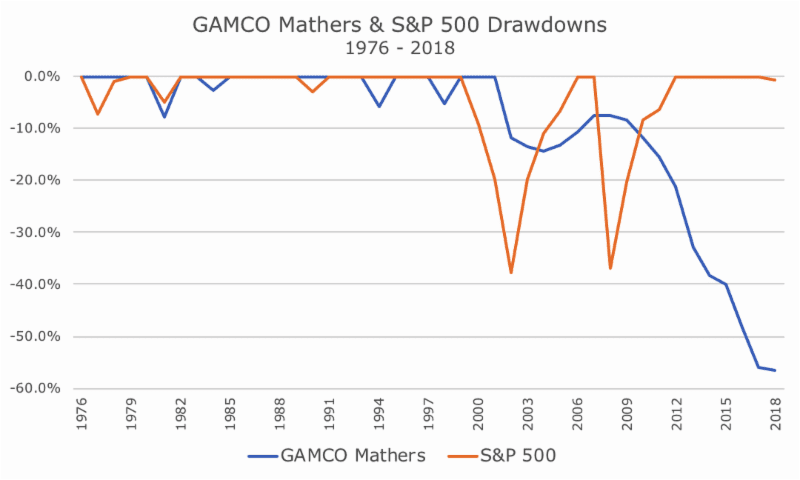

Yes, you’re reading it correctly – the fund is down more than 50 percent since it beaked in 2002. You can see both the tech wreck for the S&P 500 in the early 2000s and the 2008 financial crisis, but those don’t compare to the damage that this fund has endured since the since the 2008 financial crisis.

As soon as I saw these results, I knew that I was going to write about it, but I had no idea what happened since I had never even heard of this fund until last week.

As I Googled around, I found this fund listed in Kiplinger’s article from 2007 that included the fund in a ‘Hall of Shame’ list of terrible funds (you can find the article here).

The article doesn’t say much, but it does pronounce the manager, Henry Van der Eb, a permabear. He’s been the manager since 1976 and still runs the fund today.

Looking at the results, I would say that there are three distinct phases for this fund. The first, from 1976 through 1991, was awesome. The fund earned 17.5 percent while the S&P earned 14.9 percent. That’s a long time to do so well, and I am certain that Mr. Van der Eb was rightly considered brilliant.

The next phase of the fund, from 1992 through 2008, the fund earned almost nothing – just 0.6 percent per year, while the S&P 500 earned 6.7 percent. Our proxy for cash earned 3.7 percent per year during this period, so you could say that it was a tough stretch, except that as we saw above, it’s about to get worse.

In the third phase, which starts in 2009 and ends with the first quarter of this year, the fund falls at an annual rate of -7.3 percent. Wow! The fund’s stated benchmark, the S&P 500, earned 13.5 percent. Cash, which as been anemic since the crash, managed to scrape out 0.2 percent per year.

I don’t know exactly what happened to the fund. I’m not a journalist, so I didn’t call them for comment and I didn’t find anything on Google.

Here’s my theory. Mr. Van der Eb believed in stocks at the outset, took risks and his swashbuckling paid off handsomely. If we think about his results in cumulative terms, he knocked down a 1,211 percent return during his first phase when the S&P 500 ‘only’ made 822 percent.

Then, I think he got cautious, maybe over valuations. I was just starting to pay attention to stocks during college when he results started to cool off. I remember my finance and investments professor talking about how risky markets looked at that point.

Again, I don’t know what happened, but I suspect that Mr. Van der Eb thought that the ‘big one’ was coming any day for the following 17 years while his fund earned almost nothing. And then, the crisis does come in 2008 and he earns 0.2 percent while the S&P 500 loses -37.0 percent.

At that point, I assume that he thought that things were only going to get worse – much worse, because it appears from his results that he wasn’t content to hold cash and shorted stocks. According to the most recent filing, he’s about half of the fund is short stocks.

As I researched this last night, I saw that the fund will be liquidated at the end of the month. I’m not surprised given the results, which has caused assets to dwindle down to six million dollars.

I wonder why they didn’t shut it down sooner, which gets me back to the elephant’s graveyard. He’s only 73, which seems younger and younger as I get older. I suspect he has had the respect of Mario Gabelli, the founder of GAMCO, thanks to Van der Eb’s spectacular results 30-40 years ago.

If that’s what happened, I think the kind thing for everyone would have been for Gabelli to kill the fund years ago and simply let Van der Eb office at GAMCO’s headquarters.

I hope that when my day comes, the Young Turks running Acropolis will put me out to pasture kindly. I’ll come to the office to read the paper, get stock quotes and make tennis appointments. I don’t play tennis, but that’s a long way off, and you never know what the future holds.