Over the weekend, I watched a Front Line documentary on PBS that came out in July, called The Power of the Fed. You can watch it here, although you may have to be a member (like me!).

The documentary chronicles the power of the Federal Reserve, with particular attention to the bond-buying program called quantitative easing that followed the 2008 global financial crisis.

The documentary makes the case that the Fed created asset price inflation in stocks, bonds, and real estate, and most of the people they interview admit that they have no idea how the experiment ends.

I thought they did an excellent job, although there was nothing new – I’ve been hearing about it internally since 2008. However, FrontLine was able to get good interviews from economists, current and former Fed officials, and some notable investors.

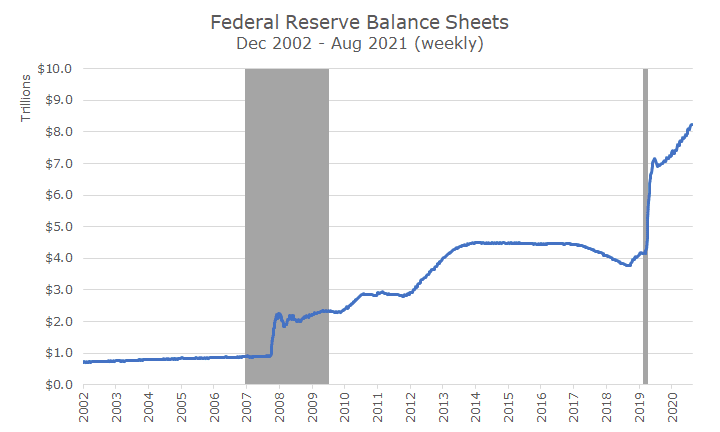

After the show, I pulled up the Fed’s balance sheet, from the St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED database, and here’s what it looks like today:

I have to admit that even though I know the Fed is out in the market buying bonds without abandon, the chart still gave me a jolt.

Prior to the 2008 crisis, and the recession highlighted in gray, you can see that the Fed carried assets and that they grew at a modest pace. It makes sense to me that they would have assets, and that they would grow gradually, along with the economy.

Then, you can see the assets skyrocket from $1 to $2 trillion dollars (yes, that’s trillion with a ‘t’). That was the initial bond-buying program, but you don’t have to look too hard to see the second and third rounds in 2010 and 2012.

Then, the assets stay relatively constant while the Fed figures out how to unwind the program. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke talks about slowing down the purchases in 2013 and the bond market has a fit, in what is now known as the ‘taper tantrum.’

Finally, in 2017, the Fed starts to allow the portfolio to run off, by not reinvesting interest payments and maturities. The discussions start to center around how far they should let it get down to, and a lot of people think that $2 billion is about where it would have been if there had been no purchases.

In 2019, however, long before we’d heard about the novel coronavirus, you can see that the Fed stops tapering and starts to add to the bond portfolio. At the time, investors were worried about a possible recession and the yield curve was inverted.

And then, of course, the pandemic arrives, and the recession (which we know now was just two months long) brings about even more stimulus than before. And, even after the initial jolt of buying, which was about three times more than in 2008, keeps going at a pace of $120 billion per month. In fact, since that initial jolt, the Fed has bought another trillion.

In July, Fed Chair Powell said that the Fed will hold accommodative policies in place until the job market has reached full employment and inflation exceeds the Fed’s two percent target ‘for some time.’

It’s possible that the strong jobs report and current inflation rate may mean that the Fed could start tapering sometime soon, but it’s hard to say. Later this month, Fed Officials will meet in Jackson Hole, which has become a ‘must watch’ for clues about where the Fed may go, so we may find out soon that change is afoot.

And while I’m happy that the Fed bailed us out twice, I am bothered by it because I don’t think we still understand the long-term consequences. It may work out just fine, but I think there are risks to the strategy that could lead to slower economic growth, higher interest rates, and other adverse effects.

But, at the same time, even though I think that the Fed’s actions have increased asset prices beyond where they might otherwise be, our approach of maintaining a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds is still appropriate.

I’m glad that we didn’t bail out when the debt went from $1 to $2 trillion, because we would have missed a lot of upside.

Just as importantly, as markets rose, we kept our allocations the same, which in a rising market means taking money from the risky assets and increasing the allocation to the safe assets. Sure, bonds have risks and aren’t safe like cash, but the downside just isn’t as low as it is for stocks (so safe may be a relative term here).

And, it’s important to remember that in addition to not really knowing what the outcome will be, we don’t have a clue for when we’ll feel those consequences. And while some people are scared that it might lead to a crash at some point (which it may), it could also just mean a long time where returns are modest. We just don’t know.

Lastly, we weren’t alone in this: every major central bank did the same thing, and I’d be willing to bet that we can afford to take the risk better than anyone else.