When markets are falling, clients often ask about whether certain ‘risk mitigation’ strategies make sense.

Mitigation isn’t a word you use every day unless you’re a lawyer or in the insurance industry, but the meaning is simple: it is an action that reduces the severity, seriousness, or painfulness of something.

Usually, when someone talks about it from an investment standpoint, they usually mean some kind of complicated hedging strategy.

Over the years, I’ve investigated a lot of options strategies, and while I haven’t found anything interesting, one strategy shows why a long-term, buy-and-hold approach to hedging doesn’t fair very well.

There is an exchange-traded fund (ETF) from a provider that I admire and respect that seeks to ‘mitigate significant downside market risk’ by investing in put options and Treasury notes (I didn’t realize they used the word mitigate in their strategy summary until after I wrote the first two paragraphs).

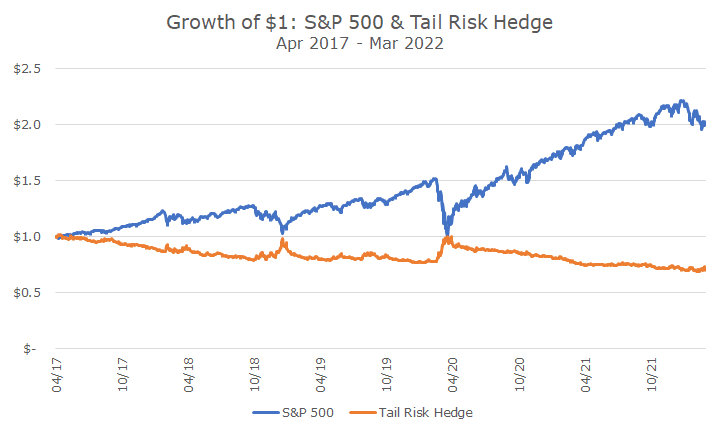

The fund has been around for about five years, so we can see how it’s managed, but to be fair in the analysis, the market has gone up tremendously during that time period.

The good news is that the risk hedging product is nearly a mirror image of the stock market, and spikes when the market falls. The bad news is that it’s lost about 25 percent over the past five years. And, it’s been about 75 percent as volatile as the S&P 500 and had a bigger drawdown.

And, it makes sense. If you want to bet that the stock market is going to fall, you have to pay a premium to buy put options. Since options are leveraged, you don’t have to use all of the money to get your short exposure on the market and can invest the difference in Treasury notes.

That bond exposure may be why the hedging hasn’t worked as well during this selloff. This particular product is up 1.7 percent while the S&P 500 is down -11.5 percent, and I suspect that it would be doing better if the bond market was in the black.

But we don’t need a lot of heavy math to see why we don’t love this approach. Yes, it provides risk mitigation for a falling stock market, but at a -5.6 percent cost per year so far, I’m not interested. I’d rather have cash that earns nothing. Or, bonds that earn something most of the time, even though they are losing this year.

Over the life of the risk mitigation fund, a 60/40 stock/bond allocation earned 10.1 percent, had a realized volatility of 10.7 percent, a drawdown of -6.1 percent, and a Sharpe ratio of 0.85 (the Sharpe ratio is a measure of risk-adjusted return, and higher is better).

If we had replaced the bonds with the risk mitigation fund, the return was 8.1 percent, the realized volatility was 6.7 percent, the drawdown was -4.7 percent, and the Sharpe ratio was 1.03.

So, if your focus is volatility, then the risk mitigated portfolio may be better because having the hedge lowers the volatility of the portfolio, which makes sense because the risk mitigation is offsetting the stock market risk directly, whereas the bonds provide a different risk.

But if you care about returns, the stock/bond portfolio is better, because it generated two percent per year more than the risk mitigated portfolio over this period. Other periods may be different, but this fund has the longest track record of this strategy that I am aware of.

But the point is that the hedge is a drag on the portfolio. It turns out that if you didn’t invest in bonds or risk mitigation and just held a 60/40 stock/cash portfolio, your return is about 1.5 percent higher than the hedged portfolio.

Rather than invest in a complex product that produces a drag on your portfolio, we think it makes much more sense to keep it simple. Risk mitigation sounds thoughtful and sophisticated, but, really, the best risk management can simply be avoidance.