I’ve written about David Swensen and the Yale Endowment several times over the years (here and here, for example) because i find both fascinating.

I first learned about Swensen in 2005, when he was heralded ‘Yale’s $8 Billion Man’ upon the 20th anniversary of taking over the endowment. The performance during that period was remarkable: 16.1 percent versus the S&P 500, which earned 11.9 percent during the same time frame. Like everyone, I was amazed – I couldn’t stop wondering how they did it.

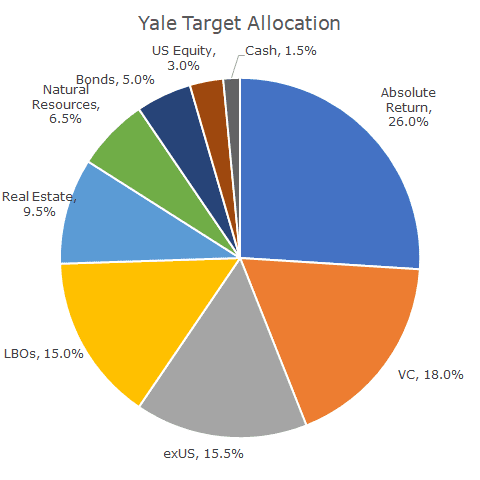

Swensen was credit for creating the ‘endowment model’ of investing that stressed an equity-oriented asset allocation that relied heavily on illiquid investments. All of a sudden, everyone wanted the endowment model.

That changed somewhat during the 2008 financial crisis when other organizations like Harvard, struggled with 30 percent losses that they couldn’t exit because of the illiquidity, which hurt the operational budget of the school.

Following the crisis, the returns haven’t been as attractive, often falling below the S&P 500. For the last 10-years, the Yale endowment earned 7.4 percent per year.

I love reading the report because they seem to reveal more and more about how they achieved their spectacular returns. In my opinion, they are being forced to share more because the returns aren’t as strong as they were before and stakeholders are demanding an explanation.

More and more, I’m convinced that their remarkable returns can principally be attributed to a large allocation to Venture Capital (VC), a strategy that seeds start-ups in hopes that they will one day become corporate titans like Apple, Google and Facebook.

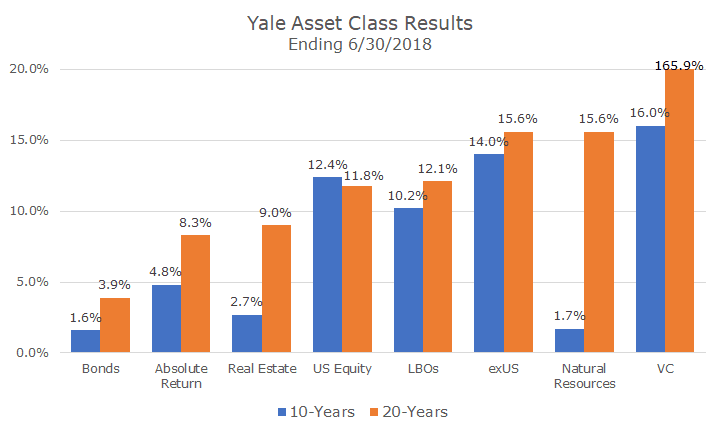

Currently, Yale allocates 18 percent of their portfolio to VC and note that their 10-year return on that portion of the portfolio over the last 10-years was 15.0 percent. Remarkably, they report that the 20-year return was 165.9 percent annually.

The returns in the chart above are impressive, but you can see where Yale has struggled in the last 10-years. Natural Resources and Real Estate, which has been big winners in the previous decade, have struggled in the last decade, partly because of the 2008 financial crisis.

Simple algebra will tell us that to earn 15.6 percent over a 20-year when the second 10-years only earned 1.7 percent as their Natural Resources did, then they must have earned 29.5 percent in the first decade. We see major reductions in returns

And you can see that they don’t have anything special going on in the bond market, where they’ve underperformed the Barclays Aggregate, which earned 3.7 and 4.7 percent over the last 10 and 20-years respectively. Absolute return, which relies in part on interest rates, suffered lower returns as rates fell.

None of this is a criticism of Yale, they’re amazing and, to be fair, these returns still include part of the 2008 financial crisis since Yale is on a June-to-June fiscal year.

I should also note that I altered the scale on the chart above and capped it at 20 percent, which understates the VC performance since you can’t see 85 percent of the bar in that chart. I did that because the rest of the chart would be unreadable if I didn’t do that.

Speaking of VC, I did a quick and dirty attribution analysis that assumes that Yale held the same asset allocation for 20-years (which I know they didn’t) and found that the VC return accounts for about 75 percent of their entire portfolio return.

Over the last 10-years, VC only accounts for 30 percent, but the return of the portfolio is much lower, which furthers the case that their big success came from VC.

The bad news is that there is no way we can replicate VC returns, they’re one of a kind. They’re so one of a kind, in fact, that most VC investors don’t get anything like Yale did.

Yale has an edge over almost everyone else in that their students graduate and head to California to start the next Apple, Facebook and Google. I don’t have any numbers, but I’d bet that just as many go out to join the premier VC firms. In an industry where access matters, Yale has a deep and wide alumni network at the center.

Stanford and Harvard have the same advantage, but sadly, Acropolis does not. Unfortunately, knowing their ‘secret’ doesn’t get us any closer to being able to get their returns.

Yale excels in a lot of areas, not just VC, and I’m a huge admirer of everything that they do. I mostly wanted to understand how they got the returns that they did, and more than a dozen years later, I’ve got an answer that makes sense to me.