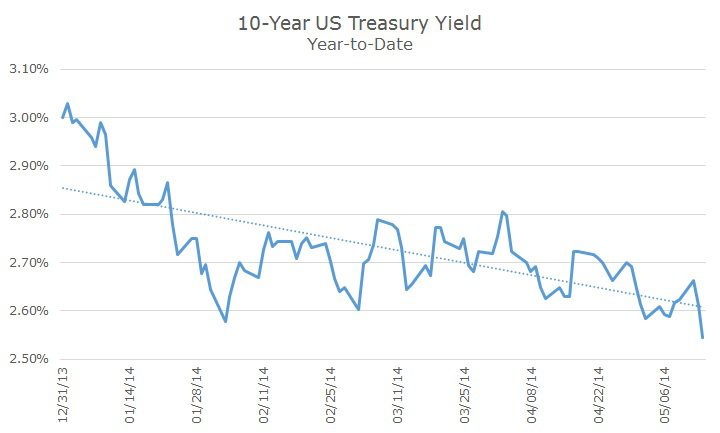

Yesterday, someone asked me what’s going on in the markets. I said that stocks are flopping around zero – plus two percent or minus two percent depending on what you look at, nothing really. I said that the interesting story, in my opinion, was that the yield on bonds has been dropping all year, much to everyone’s surprise.

When I hung up the phone, I looked up the yield and was shocked to see it was 2.545 percent – a big move from the previous day, when the yield was 2.61 percent. I realize that five basis points (or five one-hundredths of a percent) doesn’t sound like much, but that’s a big move and we’re now at the low yield for the year.

The bigger surprise though is that really no one thought that yields would drop this year and would instead rise from three percent, the yield on the last day of last year. Of course, the year isn’t even half over, so yields could still rise, but the bond market seems to be settling in on lower yields for the time being.

The forecast that I had put the most personal weight on was from Vanguard who posted a range from 2.75 to 3.50 percent. I liked that one because it wasn’t a single point estimate and was humble enough to admit that they couldn’t even say which direction yields would go. As of right now, the yield isn’t even within their band.

I’ve been humbled too. Five years ago, when the 10-year Treasury yield was at a historically low yield of ~3.5 percent, I thought that they weren’t likely to go lower, which meant that they would have to go higher.

I was wrong on both counts. First, I’ve come to believe that until rates are at zero, they can always go lower. Take a look at 10-year government bond yields around the world: Japanese bonds pay 0.59 percent and Euro-denominated bonds are 1.60 percent (unless you want German bunds: you have to pay up and the yield is only 1.37 percent).

Second, I finally realized that interest rates can go one of THREE ways – they can go down, go up OR stay the same. It seems to me that this is a fairly likely outcome, especially when you consider that I didn’t even think of it as a possibility in years past.

Although there’s no single cogent explanation for the falling yields, investors seem to be factoring in that inflation is likely to stay low for some time and central banks are going to keep their ultra-loose monetary policy in place for some time (or extended period, whatever you want to call it).

Even though the Federal Reserve is winding down their bond buying program, Yellen has indicated that they won’t even think about raising rates until the latter part of next year. Germany’s central bank indicated this week that they are willing to support stimulus measures that European Central Bank (ECB) is considering.

If you think about it, there isn’t much on the horizon that might make you think that yields will rise sharply anytime soon. It’s not like growth robust, inflation is out of control or there’s a labor shortage. All of those things will change, but there doesn’t appear to be anything immediate on the horizon.

If rates stay largely unchanged (bouncing around of course) for the next several years, having a portfolio of short-term bonds won’t far well compared to the overall bond market because the interest rates are lower (the yield curve is upward sloping). Investors with a short-term bond portfolio won’t lose money, but there’s an opportunity cost if more could have been earned in an intermediate-term portfolio or something like the Barclays Aggregate, a bond index that’s akin to the S&P 500.

Nearly three years ago, in July 2011, the yield on the 10-year Treasury was 2.79, not far from where it is today (yes, I am cherry-picking the time frame so that the beginning and ending yields largely match).

If an investor owned an index tracking the Barclays Aggregate, they would have earnings something like the index, which gained approximately nine percent, or a little more than three percent per year. If they were worried about rising rates and owned a short-term bond portfolio like the Barclays 1-3 Year index, they would have earned just less than four percent or 1.5 percent per year.

Obviously, the Aggregate had more volatility since yields fell for two years and then rose sharply last year. In the losing year, the short-term bonds outperformed the Aggregate. If you can time it, great, but we haven’t seen anyone able to do that and over this time period, there was an opportunity cost of five percent – a lot given where yields are today.

We don’t know where yields will be in the future, and that’s the point, no one does. It seems like it ought to be easy – interest rates can only do three things: go up, go down or stay the same.

Unfortunately, the same is true for the stock market and we know that no one can time that.