One of the things that I have heard many times over the years is that lower interest rates equal higher equity valuations. To be honest, I always struggled to understand why that relationship would be dogmatic.

In the past, I reconciled the idea by thinking about the price-earnings ratio (PE-ratio) as an earnings yield, which is simply the inverse of the PE-ratio. If the PE-ratio is 20, then the earnings yield is five percent (1/20).

In some sense, if interest rates fell in general, then the earnings yield ought to fall with it – there ought to be some equilibrium relationship. If earnings yields are falling, its axiomatic that valuations are rising.

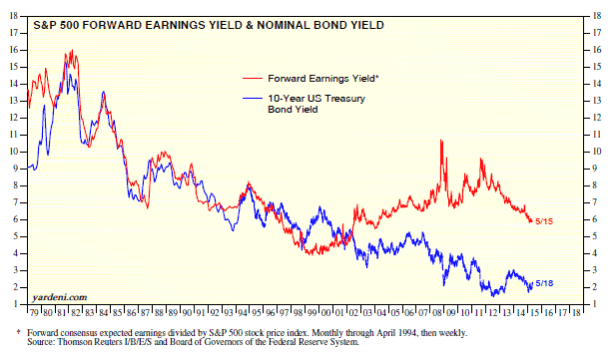

While I could follow the logic, I could never really buy the story because over the long run, that equilibrium relationship doesn’t really exist. It looked perfect starting in the 1970s as the chart below shows, but has been pretty far off the mark since the dot-com bubble burst.

* This chart comes from Ed Yardini’s website, the person thought to be responsible for calling this model ‘The Fed Model.’ Here is a link to his site.

Given today’s super-low interest rate environment, with the 10-year US Treasury yielding just two percent (or so), that would imply a 50 PE-ratio for stocks, which is beyond comical.

It’s true that with relative valuation models, you can’t always tell which input is off – are stocks undervalued in the context of a 50 PE-ratio or are bonds overvalued? The latter seems obvious, but it really isn’t given the low growth and inflation expectations over the next decade.

If you think about the most basic idea in finance, that an investment is worth the present value of it’s future cash flows, lowering the interest rate will increase the present value if you assume that the cash flows stay the same (here’s a link to a calculator if you want to fuss with the math).

This is pretty straightforward and is really how I think about the issue now, but I’m still a little unsettled because I’m not sure it’s fair to assume that cash flows will stay the same when the discount rate is reduced.

It seems to me that if I am lowering the discount rate because I think growth will be slower then I also have to assume that cash flows will be smaller in the future.

I guess what I am saying is that I still don’t fully understand when people say that it’s okay to have high valuations when interest rates are low. I can see how it makes some sense in very general terms, but it doesn’t really provide much information about the magnitude of market over/under valuation.

Personally, I still think that valuations are high, which means that expected returns over the next 10 or so years will be lower than the long-term averages. That doesn’t mean a crash necessarily (although we are certainly due for a correction), it could be years where nothing happens but a lot of price volatility (like this year so far).

I’ve been thinking and saying that since at least February of last year, so these tools can be useful for setting long-run expectations, and useless for short-term predictions.

If you’re like me, the next time you hear someone say that current stock market valuations are justified due to the current low interest rate environment, you’ll wince just a little bit.