In response to the economic shutdown caused by covid-19, the government has effectively printed almost $5 trillion dollars.

Congress passed a fiscal stimulus package of $2.9 trillion and the Federal Reserve has bought more than $2 trillion in bonds from the open market.

Moreover, there is a debate in Washington to see whether Congress should pass another stimulus package and the Fed has committed unlimited funds to fight the economic slowdown.

Inflation is often described as ‘too much money chasing too few goods.’ Given that there is now $5 trillion new dollars floating around the economy and the economy is shrinking, shouldn’t we be worried about too much money chasing too few goods?

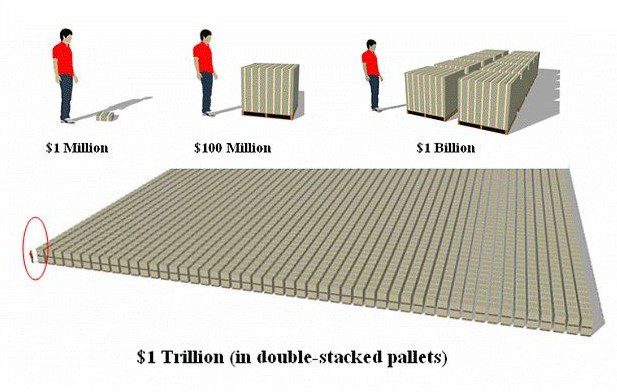

Before we look at that, let’s think about $1 trillion dollars; these numbers are just so big that they’re hard to understand. The image below shows how much stacks of $100 bills would be in various amounts.

Wow! Now remember that the monetary and fiscal stimulus packages so far are five times larger than that bottom image with more to come.

The US economy is much bigger, about 20 times larger than the bottom image at $20 trillion. Still, $5 trillion in stimulus is massive, getting back to the inflation question.

The most truthful answer is that nobody knows whether the massive stimulus will lead to inflation, but at this point, markets don’t think that it will.

One way to measure what markets think about future inflation is to look at the difference in yield between US Treasury bonds and US Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPs).

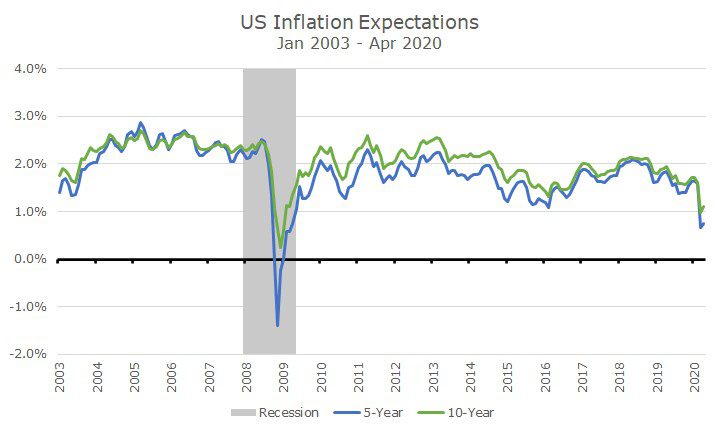

The chart below shows the expected inflation rate over five and 10-year periods since 2003 based on this metric, known as a breakeven.

While breakevens don’t tell us what will happen (wouldn’t that be great?), the chart shows a few interesting things.

First, you can see that inflation expectations over the next five and 10 years mostly hovered between two and three percent before the 2008 financial crisis.

Then, in the crisis, markets began to expect deflation over the five-year time horizon and no inflation or deflation over the 10-year time horizon.

After the crisis, inflation expectations mostly hovered between one and two percent, even as the Federal Reserve amped up their stimulus in the form of quantitative easing.

And now, like in 2008, you can see that inflation expectations over the next five and 10-years are right at one percent or so. While markets aren’t worried about deflation like they were in 2008, they are expecting lower than average inflation in the coming years.

Right now, despite all of the stimulus, markets think that the economy has slowed so much, and that so many people are unemployed, that even $5 trillion of stimulus on a $20 trillion economy isn’t enough to spur inflation.

Markets can surely be wrong (just like they were about deflation in the five years following 2008), but in the aggregate, investors aren’t worried about inflation.