Last week, I noted that in the Q&A session following the latest Federal Reserve meeting that Chair Powell said that other monetary policy tools such as ‘yield-curve control’ were still under consideration.

What is yield curve control, or YCC? Good question.

A little background first.

Now that the Federal Reserve has lowered interest rates to zero (okay, near zero, but effectively zero), what tools does it have?

We know that the Fed can buy bonds in the open market in a process called quantitative easing. We saw it following the 2008 financial crisis, and we’re seeing it again now (big time).

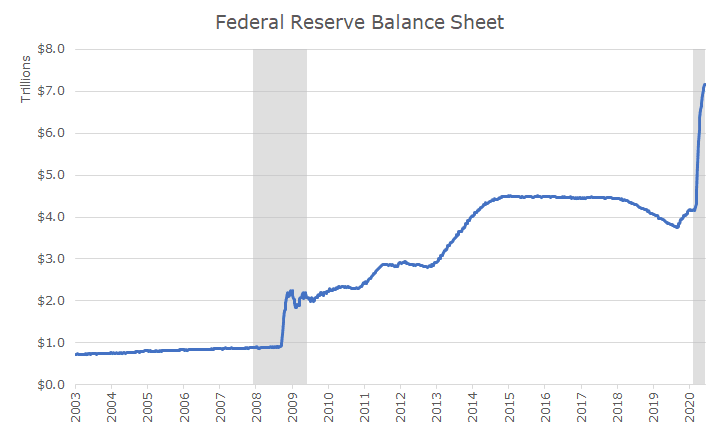

Heading into the 2008 crisis, the Fed had about $900 billion dollars on it’s balance sheet. That’s a lot, but in an attempt to stimulate the economy, they bought about $3.5 trillion dollars worth of bonds in the open market.

They were just starting to shrink their balance sheet by letting those bonds mature and not reinvesting them, but reversed course last year.

And, when the virus shocked the economy, they took it to a whole new level and have bought about $3 trillion more worth of bonds so that their balance sheet is now over $7 trillion.

As you can see, the Fed’s action is already pretty significant, but they’re wondering what else they can do. As noted above, one idea is yield curve control.

This tool would mean that the Fed would target a specific yield on a specific maturity (or series of maturities) and buy enough bonds to keep the bond yield for that maturity from rising.

Remember that bond yields and prices move in opposite directions: higher prices equal lower yields and vice versa.

So, if the Fed wanted the yield on the 10-year to be 0.50 percent (for example), they would buy enough bonds in the open market to raise the price on those bonds until the yield was 0.50 percent.

If prices started to drift lower, which would mean that yields are rising, the Fed would get their wallet out and buy more bonds to keep the price at the specified level.

In a sense, this is like quantitative easing because it involves the Fed buying bonds in the open market and increasing their balance sheet.

With quantitative easing, though, the Fed commits to buying a certain amount of bonds, $1 trillion or something, and the market assumes that they will drive up the price to some extent, but the market still (sort of) sets the price.

Under YCC, the Fed is going to dictate the price, and doesn’t say how much money it will commit to that price, except they’ve said that there is no limit to what they could do. In that instance, the Fed has set the price much more directly than it does under QE. Hence the word ‘control.’

One possible advantage to YCC is that the market might accept that the Fed will do whatever it takes to set prices and the Fed might not actually have to buy the bonds to set the price. In that regard, the Fed could have the benefit of the QE without spending the money and increasing its balance sheet.

That’s also one of the primary risks. The Fed would be putting its credibility on the line, and while the market seems to put a lot of weight on what the Fed says today, investors could change their minds and force the Fed to buy more bonds that it might have otherwise.

And there are a myriad of other risks too, such as how will the Fed end this program, is there a limit to what they can spend, or is it good to have a small group of unelected government officials set market prices?

I don’t have the answers to these questions, and don’t think that anyone else does either. That said, I’d rather that the questions stay theoretical and keep our fingers crossed that the other tools already in use actually work.