In any investment, the total return is comprised of the income earned and capital appreciation. The yield on the bond market is relatively low, so it’s been good news for bond investors that interest rates have fallen because that means that prices are higher, providing some capital appreciation in a low yield environment.

But that’s also the bad news: we’re in a low yield environment. Last year, when interest rates rose, the bond market was down, with a total return of -2.11 percent. But that short-term loss had a silver lining in that interest rates were higher, which is half of the total return equation.

Personally, I want interest rates to rise even though I know that it means capital losses for bond investors. As long as your investing time horizon is longer than the duration of your bond portfolio, the higher interest rates will more than offset the capital losses earned during the period when rates rise.

Since our clients’ time horizon is generally measured in decades (which allows them to own stocks) and the duration of the bond market is about five years, rising rates are no problem other than having to live through the rate increases.

If we thought we could time interest rates, we would hold short-term bonds until rates rise and then buy intermediate-term bonds. We know, however, that no one can time interest rates just like no one can time the stock market, so we’re content (but not thrilled) to hold onto bonds through thick and thin.

With interest rates falling, investors seem willing again to take on a lot more risk in order to earn a higher yield.

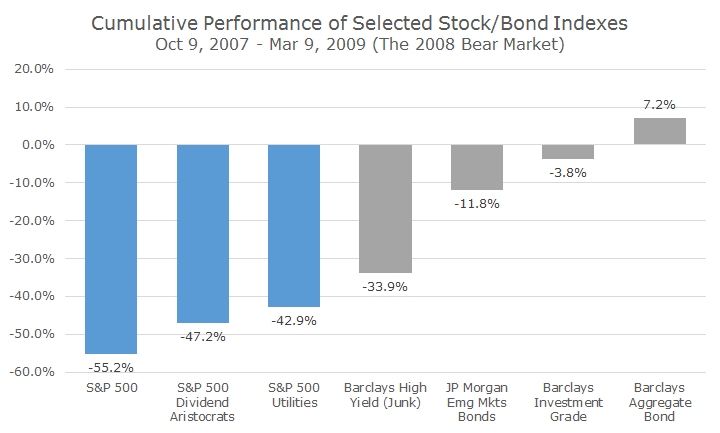

One of the most popular strategies over the past five years has been to shorten the duration of the bond portfolio and increase the credit risk, often with junk bonds, bank debt, or emerging market bonds.

All too often, investors seem to forget you can lose a lot of money when you loan money to companies or countries that might not be able to pay you back.

Even more troubling, though, is when investors want to buy stocks with their bond money because the yields are higher. Utilities are a popular example because the yields are relatively high.

The SEC-yield (an imperfect, but standardized measure) on a popular Utilities ETF is 3.54 percent, compared to 1.87 percent for the S&P 500 and 2.07 percent for the Barclays Aggregate bond index.

While it’s true that utilities are less volatile than the overall stock market, they don’t make for good bond replacements. Back in the 2008 crisis, utilities stocks fell by 29 percent.

Reaching for yield is generally a bad idea and I think in the back of most people’s mind, they know that extra yield comes with additional risk.

As we frequently say, risk and return go hand in hand and there are no free lunches out there.