I suspect that, at some point, everyone has heard the old rule of thumb that retirees need to replace 80 percent of their income in retirement to continue to maintain their lifestyle.

Although I think that the rule is conceptually reasonable, it’s imperfect and can be improved upon. At the very least, spending in retirement isn’t fixed – it tends to decline over time as people age (for more on retiree spending, click here).

Today, though, I want to look at the rule of thumb, imperfect as it may be. JP Morgan did an interesting analysis of the rule that shows how to get to the 80 percent number and the source of the income, which implies how much savings you may need.

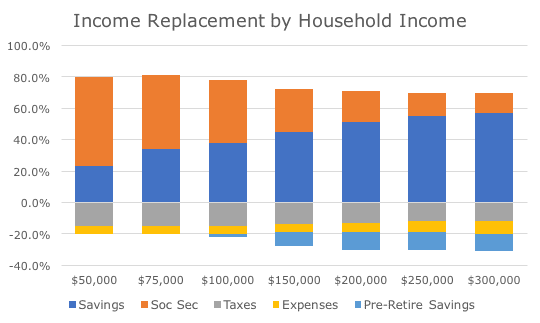

The chart below broadly depicts the JP Morgan data, but with a twist of my own. The left hand column shows that 80 percent of $50,000 will likely be comprised of Social Security (in orange) and personal savings (in dark blue).

They argue, correctly, that taxes and some expenses incurred during the working years, in grey and yellow, don’t exist in retirement, which is what accounts for the difference between employment and retiree income.

In the far right column, where the employment income is $300,000, you can see that the percentage of replacement income declines, in part because you don’t have the savings that you were doing while still working (in light blue). In other words, there’s no contributing money to your 401k in retirement.

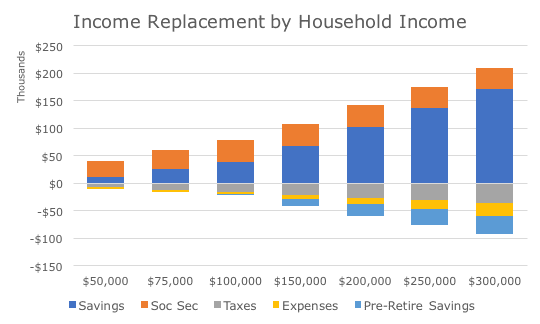

The main takeaway from comparing the far left and the far right columns is the proportion that Social Security will cover and how much you will be responsible for from your personal savings. Since their chart doesn’t full express this in my opinion, I took the same data and converted it into dollars.

Looking at the data this way, you can see how much your savings would need to cover. In the far right column, Social Security would cover $39,000, but your savings would have to generate $171,000.

If we take another rule of thumb, we can see how much savings you would need to cover the spending. The four percent rule suggests that your portfolio can spin off four percent of its value each year without too much risk of running out of money. This rule is a little more dangerous than the first one, but I’ll save my critique for another day.

If we use this rule despite its issues, it would suggest that to generate $171,000 in income, your portfolio would need to be $4.275 million. The person on the left, who is mostly replying on Social Security, ‘only’ needs a portfolio of $287,500.

These rules of thumb are reasonable mental models for quick and dirty analysis. I use them all the time to set baselines, but, ultimately, I rely on our more detailed models that incorporate much more data and analysis in the process.

In the 15 years that we’ve been doing this, I’ve found that while most people have the same broad goals, that everyone’s circumstances are different and the rules of thumb don’t really apply when you get down to the nitty gritty. Still, I thought the JP Morgan data was interesting and worth a quick look, although I’d encourage you to come in for a more thorough analysis anytime.