One of the things that I hear all the time these days is that the bond market and the stock market aren’t in agreement about whether a recession is coming.

Usually, I hear this from someone who thinks that the bond market is right and that the stock market will correct sharply when the recession comes.

And in fact, bond investors are giving strong signals of a recession from the inverted yield curve to the probability of Fed cuts in the relatively near future to the high volatility observed in the Treasury market.

I read an article over the weekend that made me wonder what the junk bond part of the market was saying about a recession. All the signals I referenced above are about rates, but junk bond yields are about spread, or the difference between the yield on Treasury bonds and junk bonds.

High-yield bonds (often called ‘junk’ bonds) are issued by companies with low credit ratings that are considered non-investment grade by credit rating agencies. They usually have a lot of debt and are generally weaker financially, so they are more sensitive to an economic slowdown.

The difference in yield, or spread, often signals what junk bond investors think may happen to the economy because they want a higher yield (which means a lower price) to compensate for the heightened risk.

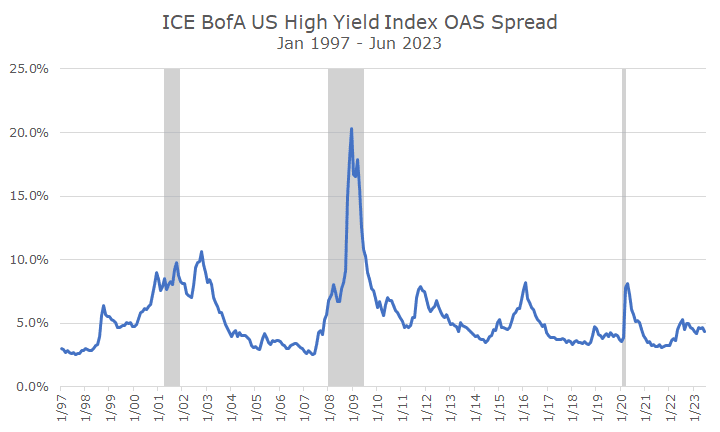

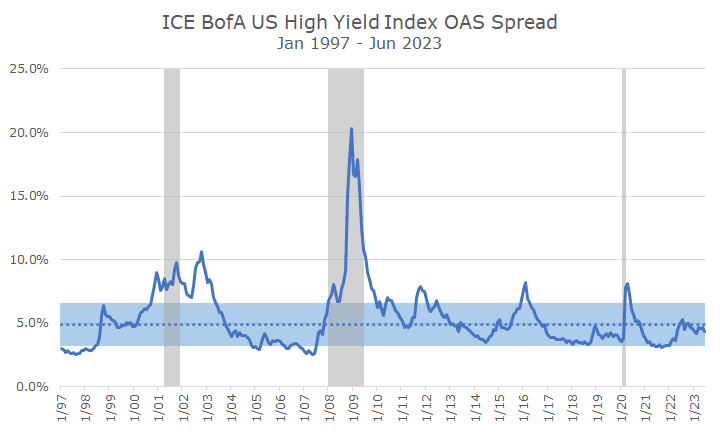

The chart below shows the spread of the ICE Bank of America High Yield Index, courtesy of the St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED database.

For this period, the average spread between Treasury and junk bonds is 5.4 percent. If you remove the recessions highlighted in gray, the average yield is about 4.9 percent.

Before a recession, you can see that the spread increases, but when I looked at it in more detail, you couldn’t tell the difference between the higher rate (5.5 percent for the six months leading up to a recession) and regular noise around the average.

There are also times when the spread goes up, but there’s no recession, and it stays high after the recession ends. Since there are only three recessions in this time frame, it’s hard to draw any real conclusions.

I did, however, look at the noise around the average non-recessionary spread, and I highlighted the average with the blue dotted line and the noise with the blue shading.

Given that the current spread is just below the average and well within the noise, I don’t think we can conclude that the high-yield part of the market is all that worried about a recession in the short run.

Of course, we may still get a recession in the 12 months, but the point is that it’s hard to predict in advance. During a recession, people will tell you how obvious it was and cite factors like the inverted yield curve. There will likely even be an explanation for why high yield spreads didn’t blow out, as you might expect them to before a recession.

The truth is that the future is hard to predict, so we don’t adjust our portfolios based on recession forecasts. I thought a recession was likely this year and said as much at the Acropolis Investor Social in January.

If we had sold stocks, though, based on a forecast, we would have missed the S&P 500’s double-digit gain so far this year. That rally is based on a small group of stocks by the S&P mid-, and small-cap indexes are both up mid-single digits. And the MSCI ACWI ex US, which measures all of the stocks outside of the US, is up in the high single digits.

Those returns might not hold through the end of the year, of course, especially if it looks like we’ll enter a recession early next year. But they also might move higher from here if we avoid a recession altogether.

The best approach to prepare for a recession isn’t to adjust your investment strategy, which is designed to be evergreen. The best thing to do is ensure you have enough emergency cash, be prepared to make IRA contributions or do a Roth conversion if the market falls.

As the old saying goes, you can’t predict but you can prepare.