I heard an amazing statistic a few weeks ago: Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s investment vehicle, could lose 99 percent of its value and still enjoy a track record that beats the S&P 500.

Over the weekend, Berkshire released their second-quarter earnings, which reminded me of my newfound fact, so I pulled up the data. Sure enough, it’s true. And perhaps even more remarkably, it’s been consistently true since the year 2000.

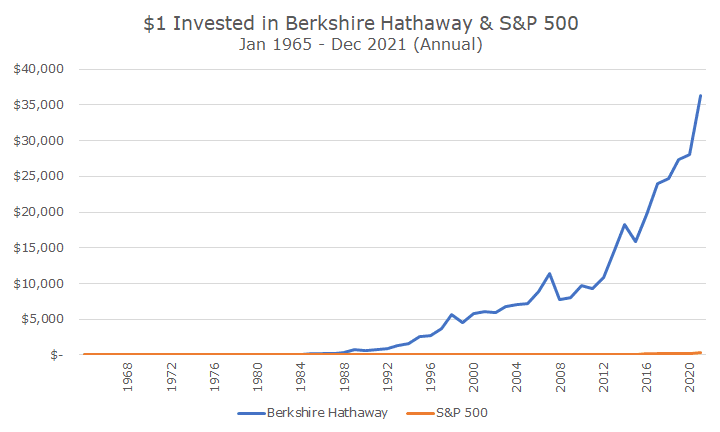

And when you think about it, it’s intuitive since $1 invested with Buffett in 1965 would be worth $36,359 at the end of 2021 (I used the data in Berkshire’s annual report), and $1 invested in the S&P 500 over that time frame would be worth $298.

The return on the S&P 500 was pretty good at 10.5 percent, but Buffett doubled that, earning 20.2 percent. When you look at a simple graph of the returns, it’s almost comical because it looks like the S&P 500 didn’t do anything when we all know that a 10 percent return is pretty darn good.

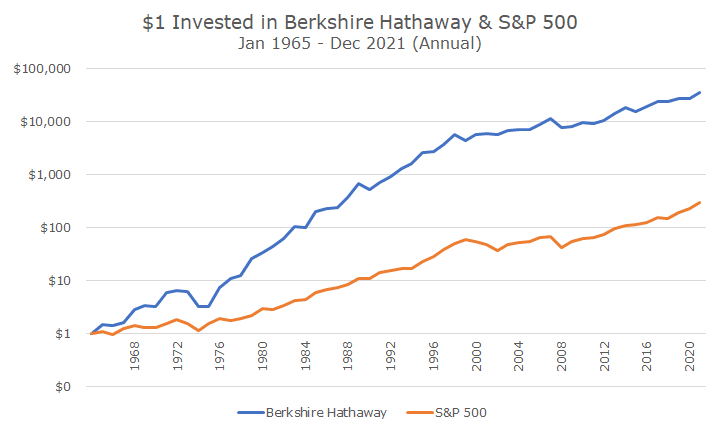

If I change the scale from linear to logarithmic, you can see that the S&P 500 was a good investment (although Berkshire was still a lot better).

I first heard about Berkshire in high school from a friend whose dad was a stockbroker. Although I don’t remember exactly what year it was, I think it was 1988 because it was $300 a share, which was much higher than the other stocks at the time.

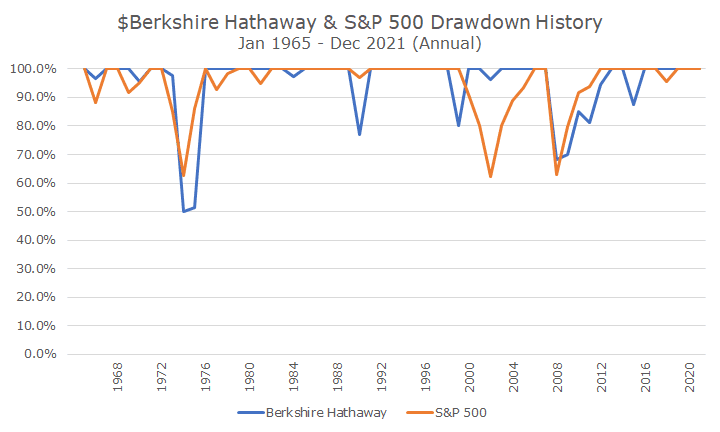

I didn’t buy it, but if that year is correct, I doubt I would have held onto the stock. In 1990, the stock fell -23.1 percent, while the market only dropped by -3.1 percent. Maybe I would have hung on since it was up 84.6 in 1989, but I probably would have sold thinking that it had run up ‘too fast,’ and I should cut my losses. Who knows – I was a kid!

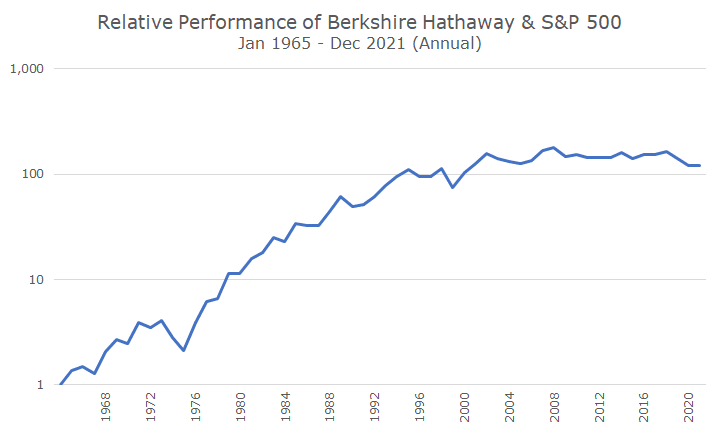

As I wishfully looked back at what I didn’t buy, the other interesting thing is that most of the outrageous outperformance happened before I got the tip in 1988.

The chart below shows the relative outperformance of $1 invested in Berkshire versus the S&P 500. By the mid-1990s, $1 invested in Berkshire was 100x more than $1 invested in the S&P 500. A few decades later, that’s still true.

Like many good investments, you had to buy Berkshire early to get most of the outperformance. Don’t get me wrong, Berkshire investors did well, but not much better than S&P 500 investors.

Buffet has said almost from the beginning that it would get harder to outperform as Berkshire got bigger. In the early days, he took big bets – I remember reading that he had more than half of his hedge fund (before Berkshire) in a stock that made baseball cards.

Today, Berkshire is both massive and massively diversified. At the end of last year, the assets on the balance sheet were worth $958.8 billion. The portfolio of publicly traded stocks, which is almost 50 percent Apple, is worth $350 billion.

Berkshire’s biggest businesses, insurance, railroads, and energy, only account for 40 percent of the total revenue. The fun companies that he always talks about, like See’s Candies and the Nebraska Furniture Mart, aren’t big enough to appear more than a dozen times in the annual report. After all, he has almost 70 operating companies.

I admire Buffett and Berkshire immensely and take care to read his annual report each year. I’ve learned a lot from him and am glad that he put his annual meeting online a few years ago, so I didn’t have to pilgrimage to Omaha.

I’ve also stopped kicking myself that I didn’t buy Berkshire in high school, partly because I’m kicking myself that I didn’t buy Amazon, but that’s another story altogether (I was a customer as early as 1999).