In recent weeks, I’ve written about two well known risk factors, the size premium and the value premium.

Today, I’ve got a more difficult topic to cover: momentum. Virtually everyone agrees that you can find evidence of momentum in the data, but there’s a lot of disagreement about why it exists and how it should or shouldn’t be applied in the real world.

In short, momentum is the tendency for stocks that have outperformed in the recent past tend to continue to outperform over the short run. The converse is true too: stocks that have underperformed in the recent past tend to underperform over the short run.

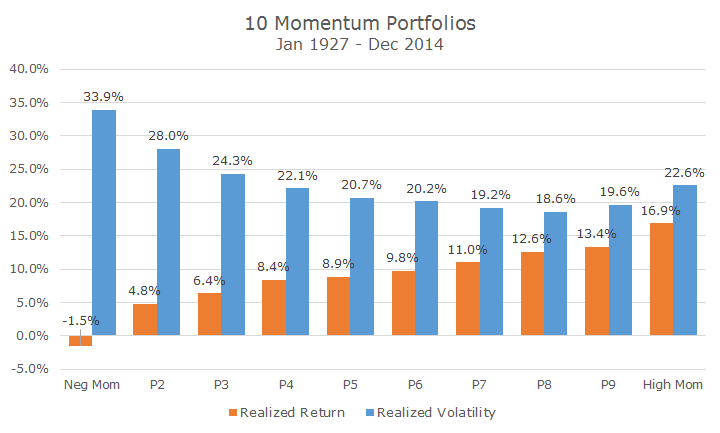

Just as researchers split the market into deciles to understand how different company sizes affect returns, academics have split the market into ten groups based on momentum, or trailing 12 month returns.

This particular data set was compiled by Ken French, one of the most prominent academics in finance today.

Stocks with the worst momentum, which I have labeled negative, or ‘neg’ momentum, actually lost money annually since 1927. The next eight labels, P2, P3, etc., are just different deciles until we reach the group with highest momentum, labeled high momentum.

What you can see from the data is that stocks with the highest momentum perform the best and stocks with negative momentum perform the worst. Keep in mind, each of these portfolios is created based on what happened the year before the portfolio was formed, so stocks that went down the most also ended up performing the worst in the next 12 months.

In an efficient market, this just shouldn’t happen. In theory, the current price contains all available information. You shouldn’t be able to look at the past year’s return to divine anything, especially since returns are the most available information. Price momentum absolutely contradicts the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

That’s not the only problem either, because price momentum challenges the idea that you need to take more risk to earn more returns. Remember that when we looked at size and value data, investors had to realize more volatility to realize more return.

While it’s true that stocks with positive momentum are more volatile than the overall market, volatility is the highest where returns are the lowest. It makes sense that stocks that are performing poorly would be risky since something bad is happening to cause the bad performance, but under classical theory (that we believe in), you wouldn’t expect to see volatility dropping while returns get higher.

That leads to the third problem: why does momentum exists? Normally there is some kind of ‘risk-story’ as they call it in finance. Investors face a risk and require additional compensation for the additional risk by requiring a higher discount rate when valuing the future cash flows. Not so in momentum.

Even though there is no risk-based explanation, there are other plausible (though less satisfying) theories to explain momentum that tend to fall into the behavioral finance category. The most prominent behavior explanation is that investors tend to under-react to new information when setting prices (again, violating the efficient market hypothesis, which says that prices contain all relevant information).

On top of all of those theoretical problems, there are some important practical issues as well – most notably that momentum requires a lot of trading. Unlike value stocks which tend to hang around in a portfolio for five years or small stocks that tend to stay mostly unchanged, momentum shifts rapidly in relatively short periods.

To provide some context, the average turnover for the large cap momentum fund that we use was 111 percent per year for the five years ending in 2014. For the large cap value fund that we use, the turnover rate for the same period was 17 percent, which means that momentum required about 6.5 times more trading over the past five years.

The cost of turnover can show up in three ways: hard commission costs, market impact and taxes. It turns out that the hard costs are extremely low, the market impact can be low if properly traded (meaning that not everyone can do it) and the taxes aren’t as bad as you think because you realize long term gains, a lot of short term losses and low dividends.

One recent paper shows that the tax consequences of momentum are no different from value under the current tax regime, without assuming any tax-aware trading strategies, which the fund we use applies. In short, we think that the excess return associated with momentum survives the trading costs and tax consequences when properly traded.

Momentum is definitely different, but we believe that including momentum in a portfolio has the potential to add to returns and lower overall volatility, especially because we combine momentum with value (a topic for another day).