Even in today’s economic environment, coming up with topics daily can be a challenge. So, when a reader asks a question, I am more than happy to answer it in this forum.

Last week, I received a question in response to my article, ‘Chance of Recession: 100 percent.’ The reader wanted to know what the recession meant for bonds, especially in the coming months when markets will be volatile.

That’s a great question, so I looked back at the market data from 1926 through the lens of the recession data from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the folks who date recessions.

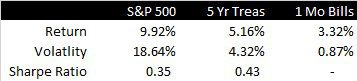

Let’s start with the baseline data for the entire period:

Stocks have earned just shy of 10 percent, but even though returns aren’t quite double those of bonds, the volatility is more than four times higher. The Sharpe ratio calculates the excess return over cash divided by the volatility and is short-hand for the level of return per unit of risk.

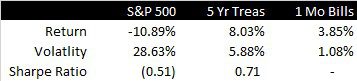

Since 1926, there have been 15 recession, that have lasted 13 months on average. Here’s what annualized market returns look like during those recessions.

It’s not surprising to see that stocks lose money during recessions, but it’s interesting to see how well bonds have done compared to the baseline returns. Importantly, look at the difference between the 5-year Treasury notes and one-month bills: it was 1.81 percent during the whole period and 4.18 percent during the recessions.

Also note that volatility for stocks and bonds are higher during recessions, which isn’t surprising either. But, instead of being four times higher, the volatility is almost five times higher.

But because stocks are forward looking and the NBER dates recessions about a year after they happen, I wondered what the numbers looked like if we segregated the recessions into two parts, the first three months and the rest of the recession.

In this case, the three-month return is annualized, but not surprisingly, we can see that the first three months of a recession is worse than the whole recession. In other words, stocks get hit the hardest at the beginning. And, because the returns are straight down, the volatility is lower (volatility is a range of returns).

Interestingly, and somewhat surprisingly, the returns for bonds at the outset of a recession aren’t anything special on average, and cash is king (speaking of client feedback, I know who I’m going to hear from based on those last three words).

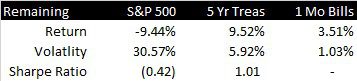

Now, let’s look at what happens in the remaining months of a recession. In fairness, this isn’t a perfect analysis because some recessions are six months and others, like 2008, lasted 18 months. Still, here are the results:

Here we see that returns for stocks aren’t good, but they’re better than the first three months. Notice how volatility is through the roof – double the baseline whole period. And, like I just said, volatility is about the range of returns; big ups and big downs.

The returns on bonds are outrageously good, in absolute terms, compared to cash and risk-adjusted.

So, to answer the readers question, historically bonds look pretty good during recessions. Bonds have been on a tear for the last year; the 5-year Treasury note, which I used for this analysis, is up 13.2 percent for the 12-months ending March 31st.

Today may not be quite like the old days looking forward since interest rates are so low. The yield on the five-year Treasury on Friday was 0.37 percent. Unless rates go negative, which they might, there may not be a whole lot more upside.

Although I wasn’t asked, the other big conclusion that we should draw from this analysis is that stock volatility is likely going to stay high. We had a big draw down, a good sized rally and we should expect more of both in the coming months.

I should also note that I included The Great Depression in my analysis. If you exclude that, the stock market returns after the first three months of a recession aren’t so bad, less than three percent annualized.

I debated with myself how to deal with that information, and I decided to leave it in the data, but also mention it here at the end.

At this point, I don’t think we’re headed for a Depression, mostly because of the policy response this time. At the same time, I don’t think we can ignore the possibility either.

Like the Depression, I think it’s reasonable to expect a sharp decline in output and high unemployment. The Depression, however, lasted 43 months, not including the follow-on recession in 1937 that lasted another 13 months.

Most economists expect this recession to be deep, but short. Vanguard, for example, thinks that the contraction in the second quarter will be the steepest since the 1930s, they also anticipate that growth will be positive in the third and fourth quarter.

And, based on current stock market levels, I would say that investors are generally in agreement. As I noted above and before, however, that assessment is going to be fluid, and prices will be choppy.

As strange as it may sound, that’s the normal process.